The Nakasendo may have been a road through the mountains and half as wide as the Tokaido which followed the flatter coastal areas, but it was very heavily traveled in the Edo period.

The primary reason for the highway system through Japan was to provide the Tokugawa shogunate with the communication network it required to govern. One of the primary users of the highway, then, were government messengers who sped up and down the road with all kinds of official documents and notes. Many of these messengers demanded fast service by runners or horses since time was often of the essence, just like today.

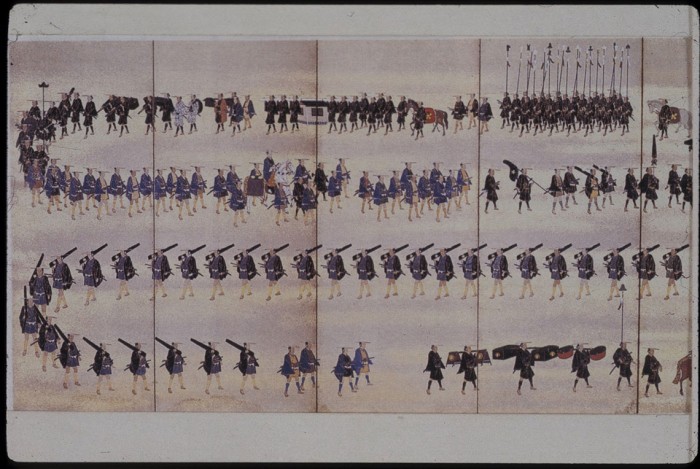

In addition, the Tokugawa shogunate placed heavy demands on the Nakasendo in accord with the sankin kotai or alternate residence system. Daimyo and their retainers and servants traveled along the road on a regular schedule. They took a more leisurely pace, spending two to four weeks to make the trip, but since a daimyo’s party could be large and their baggage weighty, their demands on the road’s facilities were heavy. Thirty-nine daimyo had permission to use the Nakasendo, but five usually resided in Edo permanently and another five had permission to use either the Nakasendo or the Tokaido.

Spies and police agents also appeared on the Nakasendo. Barriers, or seki, were established at various places such as Kiso-Fukushima to regulate and police travelers. Samurai women who might be trying to sneak away from their lives as hostages in Edo had to be tracked down and caught. Spies, on the other hand, who were important sources of political information for the shogunate, passed along with their intelligence without problem.

Occasionally, important travelers like the Princess Kazunomiya or the shogun himself might use the road. Their importance, and the size of their entourages, put even more stress on the network than usual and could cause major disruptions to life on the farms along the way.

Princess Kazunomiya

Also at the official level was diplomatic use of the Nakasendo. Japan did not have diplomatic relations of an extensive sort during the Edo period, but records of use by Korean missions, especially on the western end of the road, show a fairly steady demand, not every year, but every decade or so. There were eleven Korean missions from 1607 to 1764 which traveled the Nakasendo with the 1763 mission including nearly 500 people, giving a fair measure of the capacity of the road. After 1764, no more Koreans came to the Nakasendo since relations with them were thereafter conducted by the So family, daimyo of Tsushima island which was half way between Korean and Japan.

As time went on, commerce grew throughout Japan in the Edo period and this growth was reflected on the Nakasendo. By the middle of the period, as many as a thousand or so commoners might move along the road on a given day. There were peasant farmers going just to the next post-town, peddlers making a regular circuit, travelling merchants going to the national markets in Osaka or the urban metropolis of Edo, carpenters or stone masons looking for their next job, and many others were essentially business travelers. In addition, merchants and shipping agents used the road heavily as the rural areas close to the metropolitan areas were gradually drawn into the emerging commercial agriculture and manufacturing systems. Partially processed goods were often moved along the highway from village to village until they were finally finished and moved to the cities for sale to end-users, the consumers.

Crime was not a particular problem on the highway, but there was a steady trickle of riff-raff along the road. Some of these were petty crooks, gamblers or entertainers who made their living in the big cities but occasionally found one or other city inhospitable and had to leave for a period of time. There were others who simply made their living in the post-towns, supplying travelers with entertainment or thrills to liven up the long journey. Some post-towns, such as Mieji, had a reputation for having a concentration of low life.

serving girls trying to entice potential guests

One of the largest groups of users were pilgrims. Like everyone else, they used the Nakasendo and since a large part of their motivation was leisure (rather than religious devotion), they liked the comforts of the post-towns and the entertainment of the gamblers and girls along the way. There were sufficient pilgrims along the road that Oiwake post-town, where the Hokkokudo turned off to the north from the Nakasendo, erected a large stone lantern, the base of which was inscribed with directions: left to Ise Shrine and Mt. Ontake and right to the north country, to Nagano and its famous Zenkoji temple. It seems from the local records, however, that most ‘pilgrims’ preferred to stop here for a night – Oiwake was well known as a place of bawdy entertainment.

Not all pilgrims were rich and playful. Some were destitute and survived as beggars along the highway, yet the villages, temples and shrines, officials and daimyo all were under obligation to give donations. Such travelers caused many complaints. The better off pilgrims were also a source of complaint for often they traveled in the spring, just when some of the daimyo were scheduled to move up the Nakasendo. The two group competed for the resources of the highway.

Along the lines of a pilgrimage were trips which daimyo and other retainers of the Tokugawa were obliged to take to Nikko Toshogu, the mausoleum of Tokugawa shoguns located north of Edo. There was a separate highway leading to Nikko, but it was very heavily used, especially at important anniversaries like the 150th anniversary of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s death. At such times, many daimyo found it more convenient to take the Nakasendo out of Edo, instead of the Nikko-kaido. It also avoided clashes with the majesty of the shogun’s own procession. This helps to explain the large number of waki-honjin (nine) at Urawa, where travelers to Nikko would turn away from the Nakasendo.