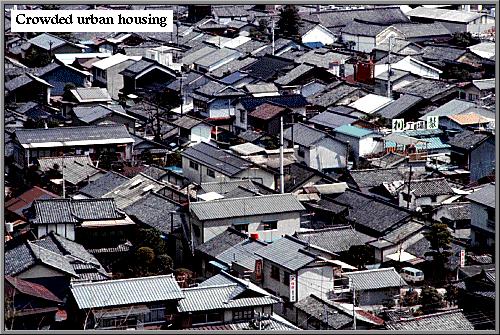

In the Edo period, urban renewal was accomplished on a regular basis as a result of fire – a major hazard which frequently swept through parts of the large cities and devastated smaller towns. Edo took particular pride in the frequency of fires and the speed with which the city recovered from them. Merchants kept large stores of lumber across the Sumida River to the east of the city so that the process of rebuilding could begin even as the ashes cooled. It was said that a store which could not reopen with three days of a fire probably would have failed anyway because of poor management. This kind of urban renewal, however, resulted in quick rebuilding of crowded, dark neighborhoods, especially in the merchant areas, rather than a process of planned redevelopment.

In the past century, urban renewal which sought to change and restructure parts of Japanese cities has not always been successful. One of the earliest examples of this is the Ginza shopping and night life area in Tokyo. This was, in the 1870s, an extravagant attempt to use Western building materials and designs on a large scale (several city blocks). It attracted considerable attention as a model, but was not immediately repeated elsewhere since it was expensive and the result was not entirely satisfactory: the buildings were reputed to be very damp.

After the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake destroyed much of Tokyo and Yokohama, there was an opportunity for government to impose planned urban redevelopment on the affected areas. The opportunity was largely illusory, however, because there were few ideas or plans prepared and because private individuals often rebuilt before government had a chance to impose any plan. One of the few projects which was implemented in Tokyo was the creation of a broad boulevard, Showa Avenue, which stretches north from Ginza to Ueno. The devastation of World War II bombing attacks again provided, through disaster, an opportunity to broaden streets and undertake other planned urban renewal projects, but neither the economy nor the will existed to impose long-term plans when there was so much immediate suffering.

In recent decades, urban renewal has seen some public projects yield limited results, but private renewal is more conspicuous. Prosperity has made real estate so expensive, that even governments have difficulty restructuring their cities. Road widening projects take years if not decades to finish in the urban centers while new transportation infrastructure has been forced to use tunnels for trains and subways or elevated highways above existing roads or old canals and rivers for cars and trucks. Only occasionally does a large piece of land become available for a large-scale project. One example is the new Tokyo government office complex which has been build to the west of Shinjuku station on what was one of the major water treatment plants.

After the economy recovered in the 1960s, large public urban renewal projects became economically feasible, but other factors inhibited them. An example is Narita airport which serves Tokyo. Land close to the city was unavailable, so Narita, sixty to ninety minutes away by expressway, was chosen. Farmers and students radicals, however, objected to the project and their demonstrations delayed completion. Just as the airport was about to open, radicals invaded the control tower and destroyed equipment, delaying the opening of the airport by another year. The dispute continues unresolved, causing the addition of a planned second runway to be postponed so long that Narita airport is nearly as overcrowded and unpleasant as its predecessor was.

shortage of habitable living space

Private individuals are much more active in urban renewal, but their projects tend to be the rebuilding of homes or offices on existing, usually small, plots of land in very crowded urban areas. In areas where land values are high, there is a tendency to build multi-story office or apartment buildings. These projects often provoke loud disputes between the redevelopers and adjacent home owners. The home owners object to the noise and inconvenience during the construction period and also to the prospect of deprivation of sunshine when the high-rise building begins to cast its shadow.

A less contentious, but equally frequent sight is the redevelopment of a individual home as a home. Families will frequently decide that their home, which may have been quickly and cheaply built on narrow streets in the 1940s or 1950s, is inadequate. They will move out for a year and builders will destroy the old house and quickly put up a new, often pre-fabricated one. The new home usually covers more of the lot than before, but it looks modern and may include modern facilities like central heating. The result of this is that many neighborhoods are gradually moving up-market in style and cost of housing, but the population is relatively stable. This contrasts with the experience of many North American cities which see people move away from older neighborhoods as individual incomes increase, leaving the older neighborhoods to deteriorate as steadily poorer people take up the empty, unwanted homes or apartments. At the same time, many urban areas contain a mixture of old and new buildings side by side.