Finding one’s way along the highways of old Japan was not difficult. The distance between post-towns was usually just a few miles, and the road was marked by namiki (trees lining the highway) and the occasional stone signpost. Ichirizuka marked off exactly how far had been traveled. Nevertheless, as with today’s traveler, most people preferred to carry some kind of map or travel guide to let them know exactly where they were on their journey.

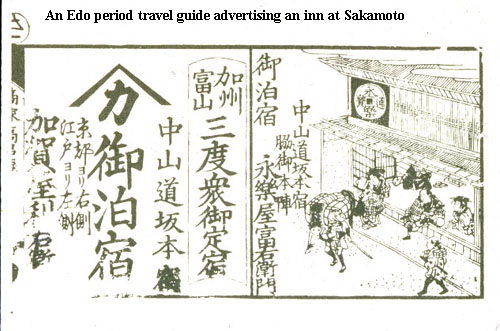

Such guides were for sale at all the post-towns, often being touted by children begging along the roadside. The guides would give basic information such as the names of the post-towns along a particular section of the highway, and a map showing the main features of the route. Descriptions might also be given of places of particular historic or scenic interest. One of the main purposes of these guides, however, was to advertise the attractions of various inns and tea houses in the post-towns. In this sense they were similar to the business directories we have today, since the owners of these establishments had to pay a fee to the publishers in order to have their business included.

A practical alternative to a guide book was to have this information printed on the back of a fan. Fans were carried by both men and women, and were essential items of equipment for travelers in the hot summer months. It is likely that many inns gave away such items as souvenirs, rather like match boxes are handed out today. Of course, the crest or mon of the inn would be displayed prominently, reminding the traveler which inn he should stay at should he pass that way again.

By the early 1800s travel guides were becoming increasingly sophisticated, developing into a literary form in their own right. Comic stories were written, for example, highlighting the more bizarre and unusual aspects of local traditions along the way. Variations in local dialects were also used as a source of jokes, taking into account the Japanese fondness for puns. The most famous of these stories was Jippensha Ikku’s Hizakurige, or Shank’s Mare. Published in serial form, the first part was issued in 1802 and was an immediate success. It tells the story of two low-life characters, Kita and Yaji, as they leave home in Edo and begin a journey along the Tokaido highway. By 1809 Jippensha had taken his characters as far as Osaka, at the end of the highway, but popular demand insisted that he continue the story. This he did by having them return to Edo, along the Nakasendo. Begun in 1812, it took another ten years for Jippensha to finish this project. In his time it is suggested that Jippensha was as popular as Mark Twain was in the United States when writing ‘Innocents Abroad’ a few decades later.

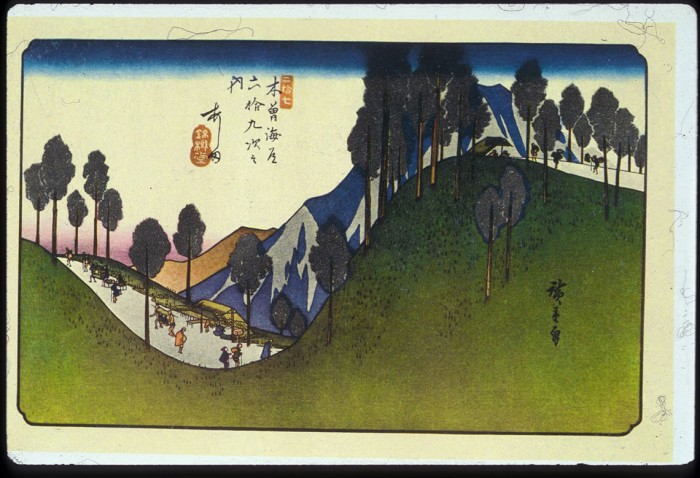

Hizakurige was eventually translated into English, and still remains a popular novel. Other forms of travel literature, while equally popular in their time have now faded into obscurity. One such form was the erotic guide for travelers. Each post-town was the scene for a bawdy story, invariably involving monks, nuns or other pilgrims and meshimori onna, a euphemism for female entertainers and prostitutes at tea houses and inns. Each scene was illustrated by vastly exaggerated erotic prints known as shunga. Rather more refined artwork showing scenes along the highways also became popular in the late Edo period. In particular the works of the artists Hiroshige and Eisen were in great demand and the remain popular today. It is interesting to note, however, that even Hiroshige had to supplement his income from time to time by producing pornographic shunga.

Another form of travel literature, though not strictly speaking intended as a guide for travelers, was the travel diary. People making a long journey, perhaps going on pilgrimage, often kept detailed accounts of their journeys and later published them. The poet Basho made many long journeys throughout his life, and kept careful record of the poems he composed on these trips. More than mere anthologies, his diaries also record the events of his journeys – such as Along the Narrow Road to the Deep North published in 1689 and eulogized recently by a series of commemorative stamps.

In the Meiji period, a new area of interest in travel guides and travel literature was exploited by Europeans and Americans. Although originally confined to the areas immediately surrounding the treaty ports, by the end of the 19th century foreigners could get permission to travel virtually anywhere in the country. This led to a mass of publications recounting travels undertaken and offering a guide to future travelers. The more accomplished of these works include Isabella Bird’s account of Unbeaten Tracks in Japan, and Ernest Satow and Lt. Hawes Handbook for Travelers in Central and Northern Japan, published in 1881. Both still make excellent reading and offer fascinating insights into the way of life of ordinary Japanese in the late 19th century.

Today, travel magazines are immensely popular in Japan. Monthly publications offer a profusion of advice on the best hot-springs, the best golf courses, and even the best love hotels. Even for those traveling by train, it is rare to find people embarking on a long journey without that month’s copy of the railway timetable. Magazines and books take great delight in relating the local specialties in craft production and food: many a book is called ‘Walking and Eating around . . .’ a local area. It is hard to tell which is more important to travelers: walking or eating.