The Tokugawa political system was perhaps the most complex feudal system ever developed. It was similar to the European feudal system (pope, emperor or king, feudal barons, and retainers in Europe compared to emperor, the shogun, the daimyo, and samurai retainers in Japan), but it was also very bureaucratic, an attribute not associated with European feudalism.

This political system was called the bakuhan system. Baku comes from bakufu which was the government the Tokugawa leaders used to administer their private affairs inside their own fief. Han means domain and refers to the 250-plus domains that existed throughout the Edo period. Thus, bakuhan refers to the co-existence of the Tokugawa government with separate, independent governments in each of the fiefs. Since each daimyo was a retainer of the shogun, the bakufu or shogunate had some power across all of Japan. This was not a federal system or even a centralized hierarchy of political authorities; rather, it was a system in which two levels of government existed with a high degree of independence.

The Tokugawa shogunate was very much like any domainal government in that it was responsible first for the administration of a limited territory, the fief of the Tokugawa house. As such, it concerned itself with controlling the samurai class, collecting taxes (primarily on agriculture), maintaining civil order, defending the fief, controlling the cities, encouraging commerce and manufacturing which were required by the fief, limiting undesirable types of commerce and so on. In most domains, the scope of government was similar. In fact, as the Edo period wore on, most domains copied the system of the shogunate.

The Tokugawa shogunate also had responsibilities and concerns which went beyond those of ordinary domains; the Tokugawa shoguns were, after all, hegemons presiding over a whole country.

The Tokugawa government alone dealt with the imperial court, the imperial nobility and the emperor himself. The emperor was the source of legitimacy since the office of shogun was an imperial appointment. Furthermore, Confucianism which was the official ideology of the Tokugawa house during the Edo period focused attention on the emperor. Thus, the Tokugawa shogunate established a monopoly on access to the imperial court. As the period wore on, the monopoly was breached, but it is essentially true that the Tokugawa controlled and manipulated the court for its own purposes.

The shogunate held a near monopoly over foreign trade and foreign affairs. The trade monopoly was important because significant profits were available to the Tokugawa alone. Foreign trade was also permitted through Satsuma domain to the Ryukyu kingdom (Okinawa) and through Tsushima domain to Korea, but generally speaking diplomatic matters were closely controlled by the Tokugawa.

Foreign relations were crucial because control of them made a statement to the political public that the Tokugawa house was in control of all aspects of government; it was an additional source of legitimacy. In line with this, the Tokugawa shogunate restricted diplomatic contact by prohibiting any Europeans except the Dutch from coming to Japan after 1639; this was the policy of national seclusion (sakoku). But even seclusion was an exercise of power which impressed observers and encouraged submission.

Perhaps the most important role of the shogunate was control of the domains, the han. This was precisely what had been lacking in the Warring States period, the ability of central authority to enforce peace. During the forty years before the Edo period, the three unifiers, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, evolved a system which proved increasingly capable of ensuring the loyalty and obedience of vassals. The Tokugawa shogunate took this previous experience and honed it to perfection.

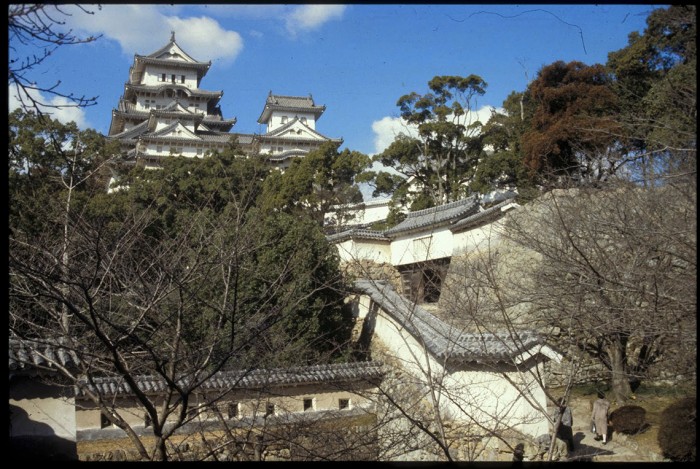

Elements of this system included a police and spy network which reported any suspicious activity by samurai or daimyo. Daimyo were required to report any proposed marriage alliances between domains to the shogunate for approval. Contact between domains was prohibited to reduce opportunities for plotting against the shogunate. The number of castles, their size and their strength were very strictly limited.

The shogunate could punish daimyo for transgressions in a variety of ways; a domain could be reduced in size, the daimyo could be shifted to an entirely different domain, or, the ultimate sanction, suicide could be demanded, perhaps with the additional punishment of his lineage being reduced in status to a non-daimyo level.

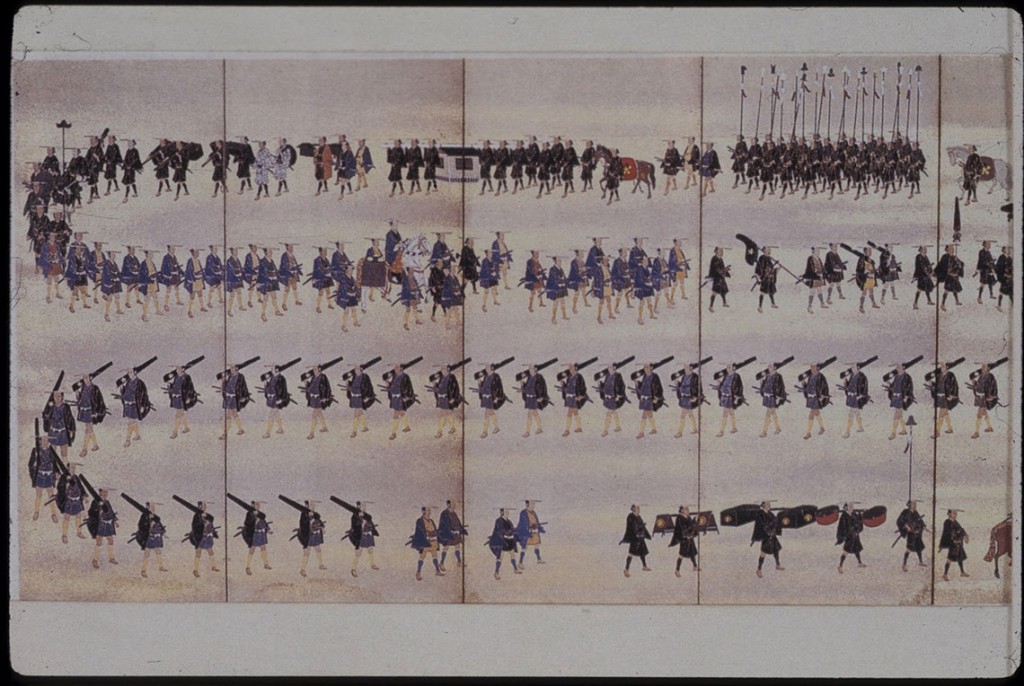

The most important aspect of the system of controlling the han was the sankin-kotai system, or the system of alternate residence in Edo. This grew out of the Warring States period practice of demanding high-ranking hostages from vassals or allies to guarantee good behavior. The founder of the shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu, was himself a hostage for nearly 13 years as a young boy.

The Tokugawa, however, formalized the keeping of hostages. They established rules which specified for each daimyo a period of time every year (or two or three) during which the daimyo must live in Edo. The daimyo’s family would have to live in Edo when the daimyo returned to his domain, so that the one stood hostage for the other.

Not only did this provide hostages, but it also placed an economic burden on the daimyo which drained away resources that otherwise might have gone into military preparations against the shogunate. The daimyo had to maintain a large residence and support facilities in Edo as well as in their domain. They also had to travel to and from Edo along a route dictated by the shogunate. Most traveled on the Tokaido because the Nakasendo was used by the imperial court, but the overall burden was spread between the two roads. The whole system consumed about 25% of the income available to most daimyo.

The shogunate was only one part of the bakuhan system, however; the domains were the other. The domains were independent with regard to their internal arrangements as long as there was no conflict with the shogunate’s interests. In practice, the domains voluntarily duplicated the shogunate’s system of government to a large degree because the interests and problems of a daimyo at his level were similar to those of the shogunate: how to maintain stability and order. Furthermore, the powers which the shogunate exercised over the domains had the effect of forcing the domains to behave in much the same manner since they were facing the same requirements.

For example, all substantial domains maintained commercial operations in Osaka, the national market, in order to sell rice and other commodities so as to raise the cash required by the alternate attendance system. This standardization did much to reduce regional differences and potential antagonisms throughout the Edo period.

Like the shogunate, the daimyo had a high interest in pacifying and controlling their subjects and the samuraiin general. During the late 16th Century, Toyotomi Hideyoshi disarmed the peasants through a series of sword hunts with the intention of reducing their contribution to turmoil and to pin them to agricultural activity alone. In the years after 1588, samurai were progressively removed from their independent fiefs in the countryside and brought into the daimyos’ castle towns to live. The samurai became separated from the peasantry both in social role and place of residence.