Toge (mountain passes) are a major preoccupation along the Nakasendo because they presented significant obstacles to travelers in the feudal period. Although they are generally not so steep that they prevent movement, they did challenge a traveler and create an impression. Passes like Torii-toge, for example, ran through countryside which is isolated even today. Edo period travelers must have worried about the occasional robber or possibly ghosts from the 500 samurai of Takeda Katsuyori, son of Takeda Shingen, who died in a fruitless attack up the pass in 1587.

More impressive than Torii-toge, or Surihari-toge with its tea house and fine view at the top, were Wade-toge and Usui-toge. Wade-toge stands tall and very empty between Shimo-suwa and Wada post-towns. It was so empty that in the early 19th century the shogunate finally ordered that a tateba be built near the top to provide rest and a reminder of civilization. Between Karuizawa and Sakamoto, Usui-toge takes the traveler from a high plateau down to the Kanto plain which surrounds modern Tokyo. This pass has the steepest paths and is the highest on the Nakasendo. It is a daunting task to cross it, but the pass provides breath-taking views.

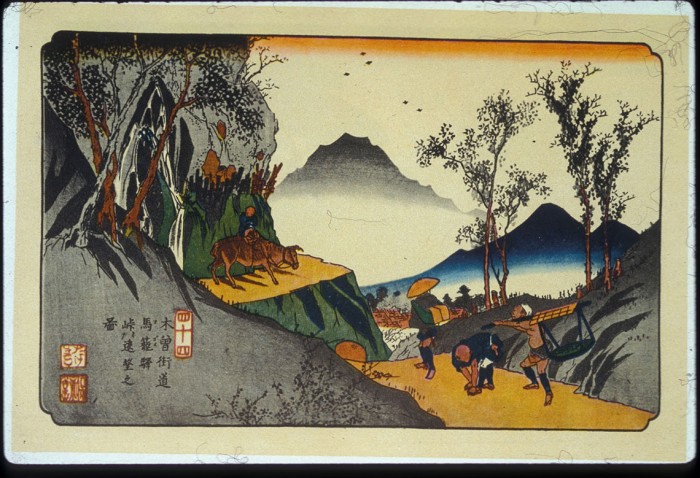

To help travelers and, especially porters and horses, most of the mountain passes were paved with ishidatami or ‘paving stones’ so that the road could be more easily maintained. Spiritual encouragement was provided by the many dososhin thought to protect travelers and horses. In particular, prayers of thanks were offered at the top of the passes, where small shrines were usually maintained.

The difficulty of ascent of most of the larger passes has meant that the original highway in these places has been largely by-passed by modern traffic, usually via tunnels running underneath the passes. Climbing the passes today, therefore, offers walkers the opportunity to rediscover some of the best preserved sections of the Nakasendo.