The Warring States period (Sengoku jidai) lasted for the century from 1467 to 1567 although the wars and confusion of the age were not finally ended until the creation of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603. The name is drawn from a similar period of civil war in China. It saw the breakdown of central authority, and an extended period of wars between hundreds of local, independent strongmen. The end saw the emergence of new methods of authority which were finally able to achieve a moderate degree of political centralization (there still remained 250 local rulers, the daimyo) and, to everyone’s relief and satisfaction, peace.

Strictly defined, the period began in 1467 with the outbreak of the Onin War and lasted until 1567 when Oda Nobunaga took over Kyoto and established a semblance of national unity. During this century, the authority of the Muromachi (or Ashikaga) shogunate, never strong, slowly disappeared. A shogunal succession dispute provided the excuse for the Onin War as aspirants to national power fought for that trophy while nearly everyone else tried to settle local disputes. After ten years, exhaustion set in, but by then, Kyoto was devastated, the Ashikaga were on the garbage dump of history and power was divided among local men of power, the daimyo.

The second half of the period saw a new kind of feudal lord, the sengoku daimyo (Warring States daimyo) emerge; men who created new systems of increasing their power through a process of trial and error. They gradually destroyed weaker opponents, and each other, on a grinding journey toward unification.

The last years of the 16th century saw more sporadic warfare, but on an increasingly large scale as three strong men gradually reunited the country under a feudal system of government, society and economy: Oda Nobunaga, then Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and finally Tokugawa Ieyasu.

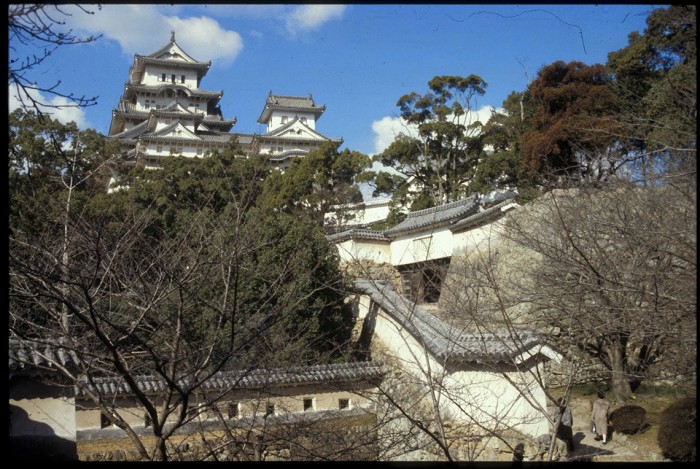

Although a period of war and destruction, the late part of the Warring States period also saw a considerable cultural flowering under the influence of Zen Buddhism and the patronage of the important daimyo. Economic growth also occurred despite the widespread warfare because the feudal lords discovered they had to encourage strong economies which could support their large armies. Agriculture was expanded through land reclamation and large irrigation projects while new mining ventures were undertaken. Cotton and jute were encouraged and commerce began to flourish along major highways such as the Nakasendo. Stores and shops proliferated in large and small towns alike, especially along the highways. Large cities devoted specifically to commerce emerged, such as Sakai which is now part of Osaka. The castles of the great lords developed into castle towns in which industry and commerce flourished with the encouragement of the daimyo.

Even foreign relations (if you include military activities) flourished during the century; relations with China were regularized by Hideyoshi while Japanese trader/pirates dominated the China coast. Thousands of high quality Japanese swords were exported to China which was in turmoil as the Manchus battled the Ming dynasty for control. A ‘Japan-town’ was established in Manila (1592), trade relations were established with the European powers, and Korea was unsuccessfully invaded.

After the battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603, two and a half centuries of nearly unbroken peace under the control of the samurai class began.