The provision of lodging for high-ranking travelers was obligatory at most post-towns, and nearly all had at least one honjin (chief inn) and waki-honjin (assistant chief inn) for such people to rest. Ordinary travelers could also stay here, provided they were prepared to pay the higher fees and no higher ranking person was already expected. For the most part, however, pilgrims and other travelers of non-samurai status would lodge at one of the many lesser inns to be found in all post-towns. The number of such inns might range from just a handful in the smaller towns to perhaps 70 or 80 in the larger ones. Lesser inns were classified in one of three groups according to size (and so status and price): large inns, medium inns, and small inns. At Magome, for example, an average size post-town, there were six ‘large’ inns, seven ‘medium’ inns, and five ‘small’ inns in addition to the one honjin, and one waki-honjin.

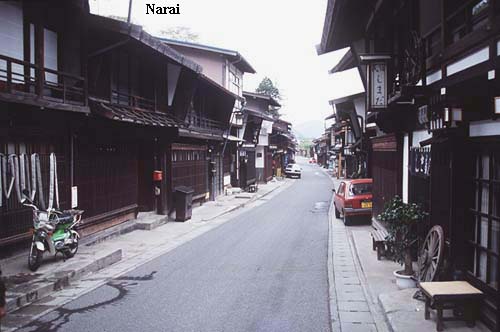

Unlike the honjin and waki-honjin, where the entrance courtyard was closed to outside view by a wall and a substantial gate, the lesser inns fronted directly onto the highway. Typically the inns were two storied, with the front rooms open to the street (as seen in many of Hiroshige’s prints), but entry often barred by a wooden lattice. Many travelers’ tales recount that, as evening approached, serving girls who worked at the inn would sit here trying to entice potential guests to stay the night at their establishment rather than go ‘next door’ – where ‘the food was not so good and the girls less appealing’. The more aggressive girls would even be prepared to leap out and attempt to drag in guests off the street.

Once arrived at the inn, by whatever means, guests would be greeted in person by the proprietor. For high-ranking guests, whose arrival was anticipated, the proprietor would go to the edge of the town to meet them. He would then hurry back in advance of his guests to meet them a second time at the entrance to the inn. In lesser inns the entrance ‘lobby’ had earthen floors, allowing guests to walk in without taking off their sandals. Rainwear and hats could be left here to avoid further discomfort from inclement weather. A typical feature of these entrances, still seen today, are the many swallows and house-martins which also seek shelter by building their nests in the rafters and under the eaves. Inn-keepers encourage this by providing shelves for nest building, one reason being that the birds help keep the mosquito population down.

The interior of the inns, as with all homes in Japan, comprised a raised timber platform covered with tatami matting, which was divided into ‘rooms’ by sliding paper screens. Guests took off their sandals before stepping up into the rooms and were led to the central part of the inn which was open to the roof to allow smoke from the fire to escape. Here they could sit around a small ash pit, sunk into the floor, in the middle of which the fire would be glowing under a suspended kettle of hot water. Maids would then serve tea while essential baggage was stored away in the rooms allocated for sleeping and the bath was prepared.

Bathing always took place shortly after arrival, before the evening meal was served. The bath house was against an outer wall of the inn since water was heated in the bathtub by lighting a fire underneath it through a small aperture from the outside. This reduced the risk of fire breaking out in the inn itself. After soaking awhile in the near scalding water, the guest then donned a thin cotton kimono (yukata) in summer (adding heavier padded robes in winter) and was led by the maid (who may have assisted during bathing) to his room. Here a low table was prepared for the evening meal and, while waiting for the food to arrive, guests might be brought sake to drink and a pipe to smoke.

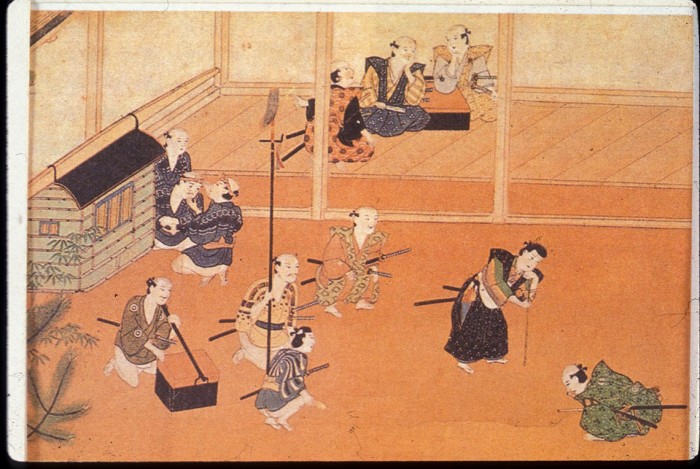

The meal might be brought by the inn-keeper himself, but the maids would remain in constant attendance to serve drinks. They would also attend to the oil lamps or candles, taking care always of the risk of fire. After the dinner table was cleared away the maids would lay out futon bedding directly on top of the tatami mats. At this point the guests might decide to retire early, or to carry on with the evening entertainment. The maids could then be persuaded, for an appropriate fee (or gift), to join in singing, telling riddles, and sharing a few ribald stories with the guests. Further financial terms might then be agreed to persuade the maids to stay even longer.

A common source of humor in Japanese travelers’ tales concerning the nights spent in inns was the fact that the paper thin walls allowed no privacy. All conversations in the next room could be heard, therefore, and it did not pay to be too indiscreet. This was something that Western travelers in the Meiji period found extremely disquieting, not least because the noise of parties kept them awake when they had nothing else they could do but try to sleep. Even when the noise died down, intrepid travelers like Isabella Bird still found sleep difficult because of the attentions of fleas which infested the tatami matting.

In the mornings the general rule for most travelers was an early start. Breakfast (comprising left-over rice and fish) would be served at daybreak, then the bill would be settled. For this the inn-keeper himself would come to the room, bowing with his head almost to the floor. The agreed sum was then passed over on a tray, in addition to any tips due for extra service. Once everyone had departed, the inn-keeper would begin preparations for the lunch-time trade, catering for travelers who would be passing through the town during the day.