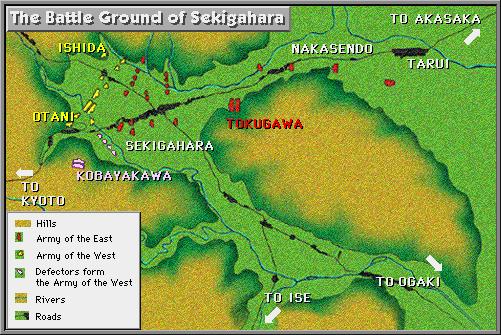

Among the soldiers forming ranks at the battlefield of Sekigahara as dawn broke on the morning of October 21, 1600, there were few who could doubt that a decisive battle here would mark the end of decades of civil strife and that, at the end of the day, a new shogun with power throughout all Japan would emerge. It was just over two years since Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a man with the power and strength to unify Japan but without the breeding and authority to become shogun, had died. Since then, the most powerful daimyo in the land, men of noble birth and regents to the juvenile heir of Hideyoshi, had continued the feuding for absolute power. Factions among the five regents had formed so that, on this day, the two most powerful contenders for the shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu and Ishida Mitsunari faced each other for the final showdown.

Ishida was better renowned for his political rather than military skills. Nevertheless, his claim to support the interests of Hideyoshi’s son, Hideyori, attracted many former allies of the old warlord to his side. His army of some 80,000 at Sekigahara included many famous warrior names of the recent past, such the Mori of Choshu, the Kobayakawa, the Kikkawa, the Ukita and the Shimazu of Satsuma. Since most of these families had their power-base in western Japan, Ishida’s forces are generally referred to as the ‘Army of the West’. Ieyasu, already the most powerful individual land-owner in Japan and with a distinguished military career behind him, was based in his comparatively new castle at Edo. Supported by his family – the Matsudaira – and some able generals such as Ii Naomasa (who had already fought alongside him on numerous campaigns), Ieyasu had also been successful in gaining the alliance of some notable daimyo families such as the Kato, the Hosokawa, and the Kuroda. Their strong power-base in eastern Japan meant, naturally, the Tokugawa forces are referred to as the ‘Army of the East’. Their numbers at Sekigahara were some 74,000.

The campaign which culminated at Sekigahara had begun with political maneuverings some months earlier. In July, Tokugawa Ieyasu was drawn away from the Regent’s Council at Osaka to defend his eastern domains from potential threat by a neighbor allied to the Ishida faction. Ishida promptly called his Western allies to arms to mount a surprise attack on Ieyasu from the rear. Ieyasu was not to be fooled, however, and his elaborate network of spies kept him informed of exactly what was going on. Having used his time to draw together his own allied forces, he set off from Edo in August to feign attack on his neighbor to the north. He then turned west with his main body of troops to thwart Ishida’s intended line of campaign.

Moving swiftly with the element of surprise Ieyasu succeeded in blocking the highways to Edo by taking Gifu castle and nearby Konosu castle. Ishida meanwhile was at Ogaki castle, having been delayed earlier in a protracted siege for Fushimi castle – just south of Kyoto. News of Ieyasu’s speed and progress shocked Ishida, and he was further confused by the misinformation spread by spies that Ieyasu’s next intention was to by-pass Ogaki castle to attack Ishida’s own stronghold at Sawayama, west of Sekigahara. Such a move, Ishida knew, would leave the path open for a march by the Tokugawa forces to Kyoto and Osaka, and to the young Hideyori. He decided on October 20th to retreat from Ogaki castle and defend the pass at Sekigahara to block any further westward movement by his enemy. This was exactly what Ieyasu wanted, for, despite inferior numbers, he excelled in open-field battle.

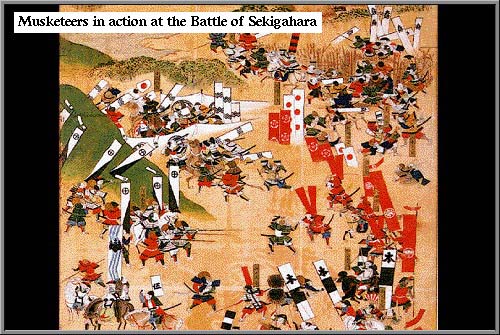

When dawn broke on the morning of the 21st the preoccupation of most soldiers was to dry their sodden clothes after a driving rain encountered during troop movements the night before. Nobody could see what was going on anyway, because a heavy mist limited visibility to just a few feet. The rival generals itched for battle, however, and at eight o’clock in the morning, as soon as the mist began to lift, the crackle of muskets sounded as the first charge thundered across the valley. The vanguard of the Tokugawa forces, led by Ii Naomasa and Fukushima Masanori, had taken the initiative and crashed into the center of the Western army’s defensive line. A battle of attrition developed as, throughout the rest of the morning, more commanders ordered their men into the fray along the wavering battle front. The Eastern army made some ground on the northern flanks of the valley, where Ishida himself had set up his command post, but the southern end of the line was stoutly defended by the battle hardened troops of Otani, who held their position for the Westerners. If the Western line could continue to hold out the day would ultimately belong to Ishida – for his defense of Hideyori against the usurpers from the east would have succeeded.

The turning point in the battle came shortly after noon. Uncommitted to the fighting so far were the forces of the Kobayakawa family, Ishida allies who overlooked the bloody field from a position on the hill slope above the southern end of the line. Ishida had already sent frantic signals to his ally to relieve the pressure on Otani by attacking the Easterners from the rear. Ieyasu also kept a wary eye on events. If the Kobayakawa forces did make such a move his cause would probably be lost. His tenseness was tinged with fury against his own son, Hidetada, who had failed so far to arrive at the battle-field with his 38,000 troops. The ace-card had already been played by Ieyasu, however. Once again his spies had been in action, before the battle, to persuade Kobayakawa to change sides and betray the Western army. When Kobayakawa finally made his charge down the hill, prompted by a volley fired at him on Ieyasu’s orders, it was against the brave Otani rather than the Eastern army that his men’s bloodlust was directed. Otani still held out for a while longer, despite being heavily out-numbered. Other defections to the Eastern army eventually proved too much though, and Otani, now faced with defeat, performed his last action that day by ripping his stomach open in the ritual manner.

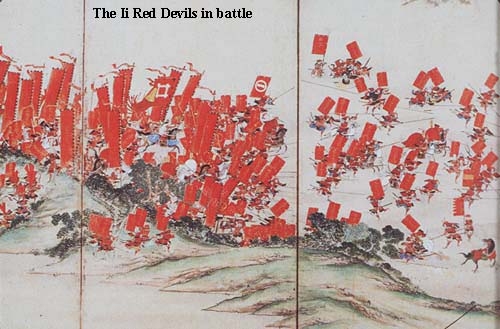

With the southern flank lost Ishida’s army now realized victory was with the Easterners. Dropping their weapons most, including Ishida himself, fled to the northern hill slopes and the shelter of Mount Ibuki. Only Shimazu remained, fighting Ii Naomasa and his ‘Red Devils’ – and wounding Ii Naomasa with amusket ball through his arm. Eventually Shimazu too recognized defeat, and was persuaded to quit the field. With retreat to the north now cut off, however, his only option was to charge through the Tokugawa center and head for the Ise road. His boldness paid off. Exchanging helmets with his nephew to confuse the enemy, he led his remaining 200 troops right past the bemused Ieyasu, with Ii Naomasa’s Red Devils in hot pursuit. Reaching the road his brave nephew, in disguise, turned to fight a rear-guard action. He was eventually overwhelmed and his head taken, but Shimazu himself did make it back eventually to Kyushu, with eighty of his men. Ishida was caught three days after the battle on Mount Ibuki, and executed with other captured leaders of the Western army on the riverbed at Kyoto a few days later.

Ieyasu meanwhile had to be restrained from wreaking similar vengeance on his son when he turned up with his forces just after the battle was concluded. After all, the way was now open for Tokugawa Ieyasu to become shogun and, in due course, for Hidetada to succeed him. It was time, as Ieyasu noted dryly, to tie up his helmet strings.

Other pages of related interest: