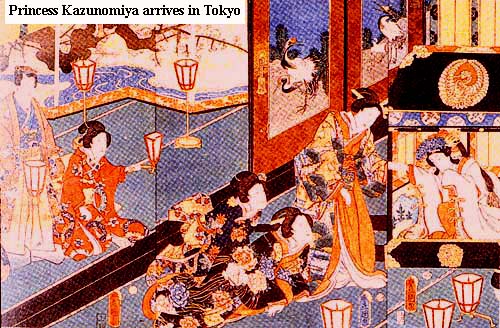

Princess Kazunomiya was the sister of Emperor Komei (reigned 1846-67) and was married to the 14th Tokugawa shogun, Iemochi, in 1862. The marriage was a political device intended to bring the imperial court and the Tokugawa shogunate into harmony, even though the princess, then aged 16, was already betrothed to someone else within the imperial court. More importantly, it was intended to quiet the antagonism between supporters of the court and of the shogunate.

This kind of marriage of the shogun or his hier-apparent and an imperial princess was not the first during the Edo period. There were others in 1731, 1749, 1804, 1831 and 1849; so many that the Nakasendo was also called the Hime no kaido or the ‘Highway of Princesses’. The princesses traveled along the Nakasendo because it was safer than the Tokaido with its broad rivers which could run out of control and a pass at Satta which had an inauspicious set of written characters in its name, at least for a bride.

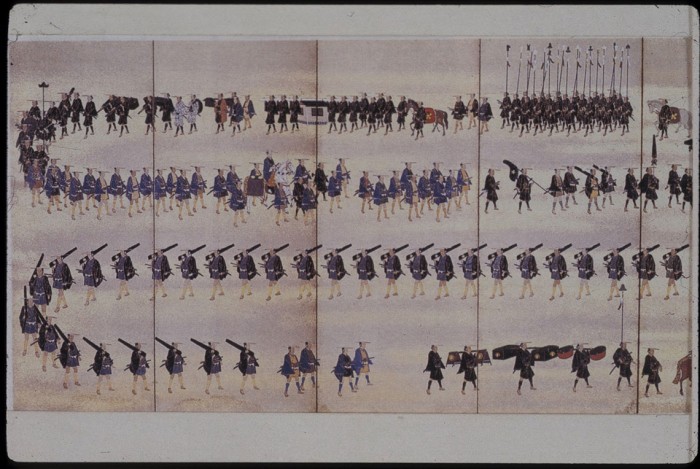

The betrothal was, however, a sure sign at the time of the weakening of the shogunate which was increasingly unable to control events. It had a serious impact on the Nakasendo, however, because Kazunomiya traveled to Edo along the Nakasendo. Of course, a princess must travel in style. Kazunomiya required various attendants and maids-in-waiting. A party of 15,000 traveled to Kyoto to fetch her and 10,000 returned in her company to Edo, not counting the baggage porters and teamsters who handled the animals. This vast train took a full three days to pass any single point on the highway.

To move such a large party along the highway would have put considerable strain on the road’s resources at the best of times. There were, after all, only fifty porters and horses maintained at most post-towns for helping transport important people like Kazunomiya. According to Annaka honjin records, post-towns had to supply 2500 porters and 200 horses the day before the procession arrived and 8000 men and 3000 horses on the days it was passing. Kumagaya post-town had to draft men and animals from 32 surrounding villages which were sukego. Mino province near Gifu simply did not have as many horse handlers in the entire province as the procession required. Wada post-town had its honjin burn down just the year before Kazunomiya’s visit. It was hurriedly rebuilt, but had to borrow utensils from the waki-honjin in order to serve her (the honjin was recently reconstructed as a museum which preserves these utensils as well as a pair of straw sandals worn by the Princess). Wada also had to call up a labor force of 28,695 men from the surrounding sukego villages to support the travellers on November 11, according to materials at the museum there.

Peasant farmers and others who lived close to the highway were obliged to provide labor to help such official parties move on down the road. This party was a tremendous burden over and above the normal traffic which the Nakasendo saw; it should be kept in mind that the ordinary daimyo’s travel party was usually restricted to 150-200 people in order to ease the burden on the resources of the highway (such as the labor of the peasants). Kazunomiya’s trip stretched the capabilities of the system to the breaking point. During her progress, post-towns were blocked to other travelers, access to fields was closed off, and the road itself was swept, tidied up, and possibly even improved with more ishidatami laid down in the passes. Everyone was put on their best behavior. In Wada, for example, orders were issued stipulating that villagers should stay inside as the procession passed; that women and children should sit formally and be quiet; that dogs and cats must be tied up; that fires were prohibited; and that roof stones should be securely fastened so an accident could not occur. There were rumors that the procession had to carry bath water all the way from Kyoto for the delicate bride, but actually she did drink local water. The procession was necessarily slow and on average only passed through 2 or 3 post-towns per day with frequent stops for the delicate Princess to rest. Thus, it took 26 days to make a journey that most travelers covered in about two weeks, October 20 to November 15, 1861.

And the middle of the 1860s were not the best of times. There was a high degree of economic dislocation and political instability due to the gathering strength of daimyo opposed to the policies of the Tokugawa shogunate which was expanding relations with Western nations. Fighting had long been occurring on a small scale, but in 1864 and 1865, the shogunate was forced to mobilize its forces and attack Choshu domain. Military action put the economy of Japan under stress and peasants and commoners proved unsubmissive. The number of uprisings against feudal authority increased dramatically.

In retrospect, it is, therefore, not surprising that Kazunomiya’s trip caused discontent among the commoners who were expected to bear the burden as well as the baggage at the tail end of the harvest season. Such, however, was the importance of the trip and the embarrassment of the Tokugawa shogunate that the Tokugawa officials were forced to negotiate with the protesters. An agreement was struck; the progress of Kazunomiya’s party was not impeded and the commoners received a guarantee that they would be compensated for economic damage resulting from the trip.

The political intention behind Kazunomiya’s marriage was not realized. After the wedding, the contending parties fell into further disagreement and any hope of reconciliation between supporters of the imperial court and the Tokugawa shogunate evaporated. The new motto of the opponents of the Tokugawa became ‘overthrow the bakufu’. Kazunomiya’s husband died in 1866 and Kazunomiya took vows as a nun.

Aside from being an extravagant piece of baggage for the shogunate, Kazunomiya also provided a focus for romantics. She is frequently remembered as having passed along the Nakasendo. Nobles and the well-born were always supposed to be poetic and Kazunomiya was no exception. At the top of the Biwa Pass, she is supposed to have turned, looked back one last time toward Kyoto and recited an old poem which is now inscribed on the large stone which sits at the top of the pass today.