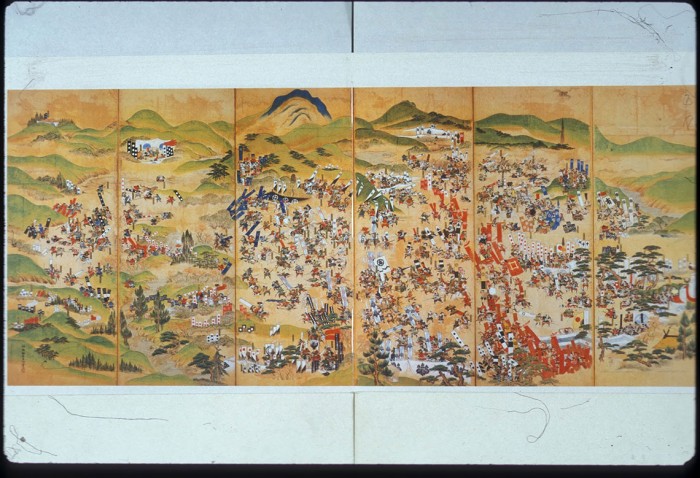

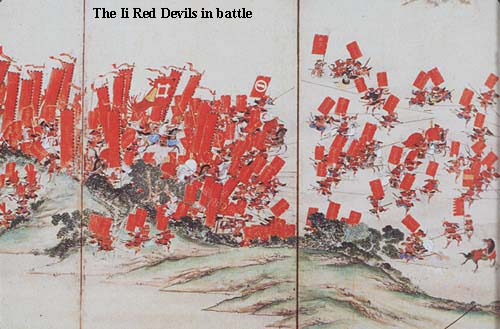

Hikone castle is one of only twelve in Japan with its original keep still intact. It is perhaps better known, however, as the home of the Ii – one of the most famous samurai families in Japan. Ii Naomasa, the founder of the line, was a native of present-day Shizuoka prefecture and a close ally of Tokugawa Ieyasu since 1578. In recognition of his loyalty and aggressive fighting spirit, Tokugawa granted the Ii warriors the privilege of dressing in blood-red armor. Thereafter, the Ii invariably occupied a prominent front line position in Tokugawa’s military campaigns. These campaigns increased in scale and intensity as the power and influence of Tokugawa grew, culminating in the decisive battle of Sekigahara in 1600.

Opposing Tokugawa and his ‘army of the East’ at Sekigahara was Ishida Mitsunari, commander of the ‘army of the West’. Both men knew that the victor of the day would, after more than three centuries of civil war, gain control over a unified Japan. Ii Naomasa, commanding the Red Devils on the left wing of Tokugawa’s army, fought with particular distinction. He led the first charge of the battle, and was wounded in the final action when he led another charge against the last remnants of opposition on the field. Notwithstanding his injury, which was dressed by Tokugawa himself, he was ordered to lay siege to Ishida’s castle at Sawayama, a few miles to the west of Sekigahara. Ishida had fled to the mountains, but his father, brother, and son had all returned to the castle to take refuge with their families. Shortly after the arrival of the Ii forces, realizing that further resistance was useless, the defenders put their wives and families to death and committed suicide. As a reward for his endeavors he was granted the castle, and surrounding lands worth 180,000 koku of rice (1 koku equals about 5 bushels). The Ii family were also assured of special status in Tokugawa’s new government, being among the 176 fudai samurai who had served Tokugawa since before the fateful battle of Sekigahara.

In 1602 Ii Naomasa died and Sawayama castle and surrounding territory (known as Omi province) passed down to his eldest son Naokatsu. The castle he inherited was decayed and battle damaged, and rather than rebuild the existing structure he decided to erect an entirely new fortress on a nearby hill called Hikone-yama. Construction of the castle began in 1603 but Naokatsu fell out of grace with the Tokugawa regime and he was stripped of his lands before his new residence could be completed. This occurred during the siege of Osaka castle in 1615 when Naokatsu refused to join the campaign. Instead, the Red Devils were commanded by his younger brother Naotake and, once again, the Ii warriors fought with distinction. At one point in the battle they succeeded in scaling the massive outer walls of the castle but, finding themselves without assistance, the Red Devils suffered heavy casualties. A few months later, in the decisive final battle of the siege, the Red Devils had recovered sufficient strength to be in the forefront of the fighting where they earned numerous distinctions. Naotake was rewarded for his services by receiving the forfeited lands of his brother and additional lands besides. Valued now at 290,000 koku, Omi province had become one of the twenty most valuable possessions in Japan.

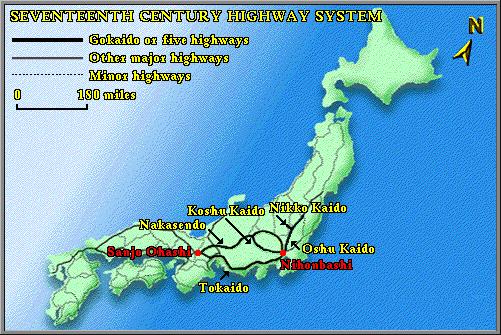

Not only was the Omi plain a highly productive rice growing area, but the province was also very important in strategic terms. Hikone overlooked the Nakasendo highway, one of the two most important overland routes in Japan connecting Edo with the western provinces. The site also offered direct access to Lake Biwa, across which large quantities of rice were shipped from adjoining provinces to the main warehousing and distribution center at Osaka. The control exercised over these vital routes from a powerful military stronghold at Hikone meant it was essential to the Tokugawa shogunate to have a loyal and trustworthy daimyo in command here. Ii Naotake’s first priority on assuming control of the province, however, was to complete the construction of the castle and surrounding town. This was finally achieved in 1622.

The building of any castle required a huge amount of labor. At Hikone, many of the massive stones for the fortified walls were dragged overland from the former site at Sawayama, while the castle itself is said to have been a reconstruction of an old castle at Otsu, on the opposite shore of Lake Biwa. Although there is no precise record of the numbers of people involved, an army of laborers, carpenters, stone-masons and tile makers must have been engaged in the project. While this was going on, the daimyo and his samurai required the services of merchants and other craftsmen to provide for their daily requirements – whether food and clothing, or military equipment such as swords and saddles. In addition to the need to find accommodation for all these people, suitable housing had to be provided for the Red Devil samurai and the army of foot-soldiers who accompanied them in battle. It was inconceivable, therefore, that the castle and surrounding town should not be constructed together, to form an integrated whole.

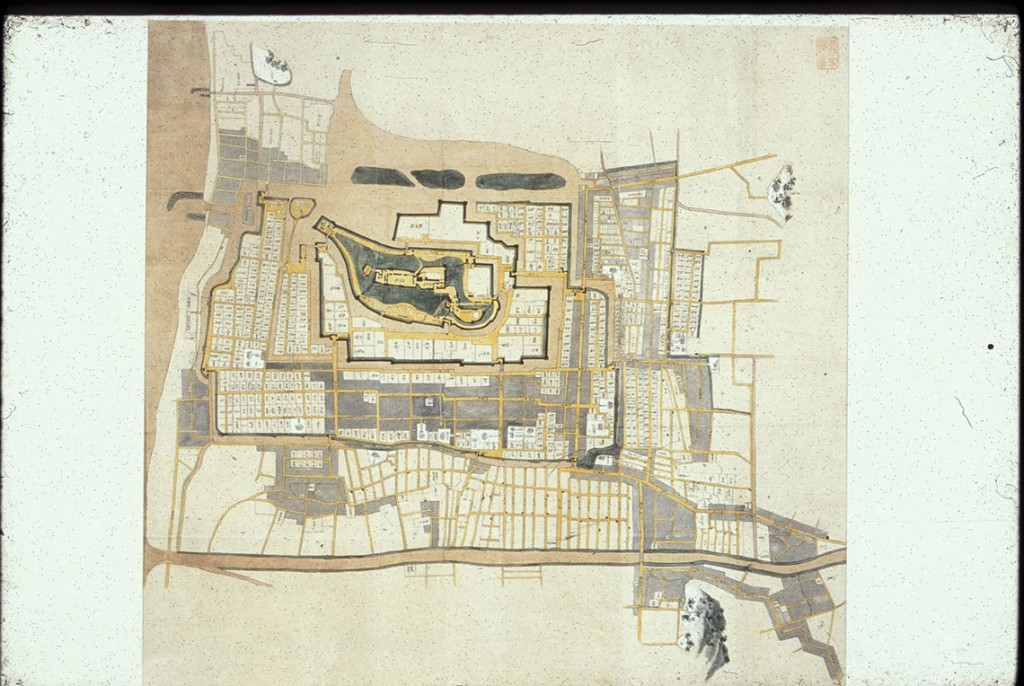

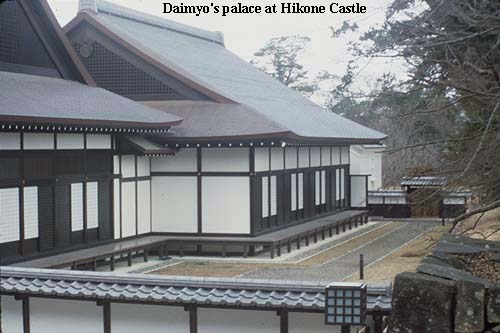

The castle itself was built on the summit of Hikone-yama. The three story keep was situated between two strongly fortified courtyards, although the daimyo lived in a separate, more comfortable villa at the foot of the hill. All these buildings were surrounded by a moat spanned, at various points, by five bridges. Beyond this moat was a second enclosure (ninomaru), also surrounded by fortified walls and another moat. Within this area were a number of official buildings, such as the daimyo’s tea-house and gardens as well as his stables, and also the residences of the most important of the daimyo’s retainers. These top-ranking samurai all received incomes in excess of 1,000 koku per annum, and held important administrative posts for the everyday management of the castle town and Omi province. It is possible, however, that many of these samurai only lived near the castle when they were required to attend the daimyo or to perform official civic duties because many of them had more spacious villas at the edge of the town, sometimes completely surrounded by open fields. These villas served an important function as defensive points guarding strategic entrances to the town. Situated at each of the four ‘corners’ of Hikone, they were particularly numerous in the southern section where a road connected the town with the Nakasendo highway. This would have been the most likely direction of attack by an enemy, and the villas here, each with a small garrison of guards, would have provided the first line of resistance for the defending forces.

Beyond the second moat lay a third, outer moat. As with the other two, this moat was also defended by a fortified wall with watchtowers at regular intervals. The area thus encircled, including the daimyo’s and high-ranking samurai residences, was known as the ‘inner-town’ (uchimachi), while the area beyond the moat was called the ‘outer-town’ (tomachi). The third enclosure of the ‘inner-town’ housed large numbers of both samurai and townspeople. The relatively high social status attached to people living in the inner-town is reflected by the size of stipend awarded to the samurai here. All had incomes in excess of 100 koku, and many of the wards adjacent to the second moat housed samurai with incomes greater than 300 koku. Kamikatahara-cho and Nakajima-cho are examples of the latter type.

Apart from the villas of the top ranking samurai, almost all the samurai residences in the outer-town were allocated for those with incomes less than 100 koku. The dominant group here were the foot soldiers (ashigaru), who lacked the full status of samurai, but who were nevertheless allowed the privilege of carrying a sword. Even amongst this group, however, social distinctions were reflected by spatial segregation of residences. Flag bearers, for instance, lived in Hatasashi-cho while old, retired soldiers were allocated quarters in Kamibanshu-cho. Other wards for foot soldiers were distributed at various places throughout the outer town, so that men could be mobilized rapidly for defense against attack from any direction. By far the largest concentration of these soldiers was in the southern sections of Hikone, near the bridges over the outer moat which provided the main access for people wishing to enter the inner town.

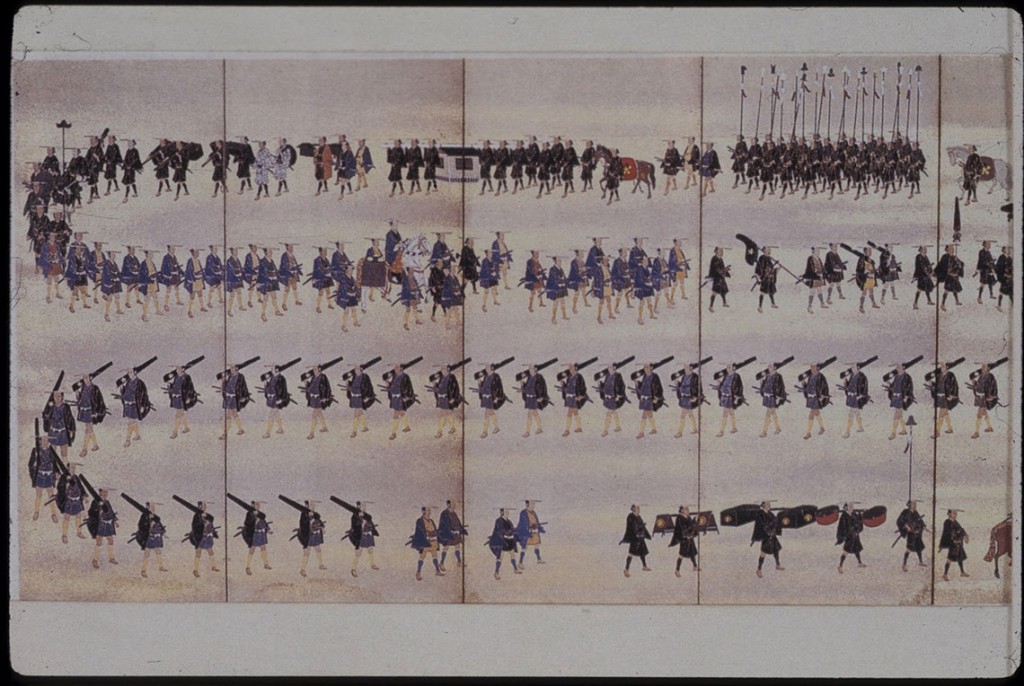

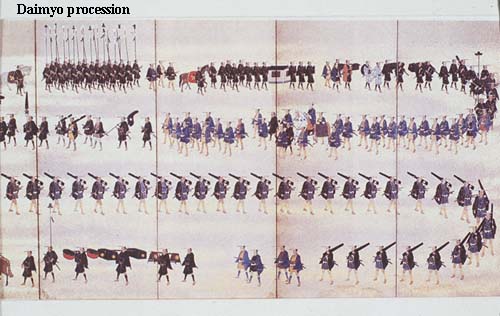

All military personnel, whether samurai or ashigaru, were normally exempt from periodic census counts of population. It is difficult to know their precise numbers therefore, although one estimate for the end of the 17th century suggests there were 20,000 warriors in Hikone at that time. This number would have fluctuated slightly from year to year, since the daimyo would be accompanied by many samurai on his regular journeys to Edo.

In contrast, it is known from a census conducted in 1695 that there were 15,371 townspeople in Hikone, living in 53 separate wards. Commercial and manufacturing activity flourished at this time, and it is recorded that the townspeople were engaged in more than 160 different occupations. To some degree, residential segregation of the chonin existed on the basis of occupational groups, with some wards allocated more or less exclusively to members of a particular craft or profession. There also seems to have been some segregation on the basis of social stratification, measured according to wealth. This is reflected in the number of servants per household in each ward, averaging 0.65 per household for chonin wards in the inner town and only 0.21 for chonin households in the outer town.

As with the samurai, it was the most influential craft groups and the wealthiest merchants who were allowed to reside in the inner town. The wards allocated to the chonin here formed a narrow strip between the second and third moats in the southwestern sector of the town, along the main route leading to the castle entrance from the Nakasendo highway. Only near the important bridges did the chonin live adjacent to the moats, since these areas were normally reserved for samurai. In 1604, shortly after construction of the castle commenced, four wards were established in this area for the townspeople. The earliest inhabitants here were chonin who had originally been established in Sawayama castle-town, but who moved to Hikone on the orders of the daimyo. By 1695 three of these areas -Honmachi, Sawacho, and Shijukucho – had very mixed retail and service functions, including wine shops, grinders and polishers, doctors, mat (tatami) makers, rice dealers, carpenters, dyers, and linen shops, while the fourth – Uoyacho – specialized in fish mongering.

As the building of the town progressed, more and more people came to live in Hikone and many additional wards were established. Within the inner town a number of specialist retail and craftsmen’s wards were set up in the southern section, including the oil sellers ward (Aburaya-cho), the carpenters ward (Uchidaiku-cho), the coopers ward (Okeya-cho), the ostlers ward (Tenma-cho), the dyers ward (Konya-cho), and the sword-makers ward (Kajiya-cho). In the outer town, the original Hikone village became a ward in its own right (Hikone-cho), while a further craftsmen’s ward was established in the north-eastern sector for tile-makers (Kawarayaki-cho). Further expansion was mostly concentrated along the road leading south to the Nakasendo highway, where a great variety of retail shops were established to cater for the needs of the many travelers passing through Hikone. Typical of the wards in this area was Hashimukai-cho, where 28 different service and retail functions were evident. These included dyers, carpenters, tea-houses, general provision stores, engravers, cotton sellers, oil sellers, confectionery stores, candle makers, rice dealers, and fishmongers.

Throughout the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, as memories of civil war receded, the relative importance attached to military and defensive aspects of the town layout diminished. Likewise, a degree of inter-mixing of different social and occupational groups within each of the town wards began to occur, especially in the outer town. Nevertheless, maps of this time suggest that the town had not expanded much beyond the wards defined in the 1695 census. Even the names of various ‘occupational’ wards remained the same. A most significant change did occur after 1868, however, when the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown and imperial rule restored under the Emperor Meiji. In effect, Japan had entered the modern period.

Immediately following the Restoration, Hikone lost its status as a military stronghold, and the old feudal class system was broken up. The samurai, as a distinct social group, effectively disappeared, and all military and social ties between the daimyo and his warriors were broken. While the Ii family continued to reside in the castle, indeed the elected mayors of Hikone until recently were direct descendants of Ii Naomasa, many former high ranking samurai appear to have left the town shortly after 1868. By 1891 many of their former residences, particularly in the area around Nakajima-cho to the north of the castle, had been dismantled and the land converted to mulberry plantations. Silk and textile production were Japan’s formative export industries at this time and, at about the turn of the century, two spinning factories were established on this site. Also, most former residences in the ‘second enclosure’ (ninomaru) were converted to other uses. This area had always been associated with civil administration and it seems appropriate that a school was established in these spacious grounds (in 1888), and also the district court (in 1890). Elsewhere in the town, some of the larger detached villas of the former samurai were also converted to schools, hospitals, and buildings for public administration.

Another change, perhaps the most noticeable one when old and modern maps of Hikone are compared, was the gradual filling-in of the third moat. This is shown still to exist on an 1891 map, although it seems that by then the moat had been drained and used for rice cultivation. By 1950, however, the fortified walls of the moat had been pulled down, and the ditch filled for construction of a road. The old distinction between the ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ towns also disappeared, therefore. The small, shallow lake to the east of the castle, into which all the moats had drained, was also reclaimed at the end of World War Two and converted to agricultural use.

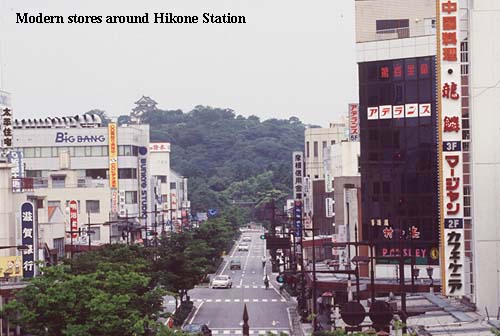

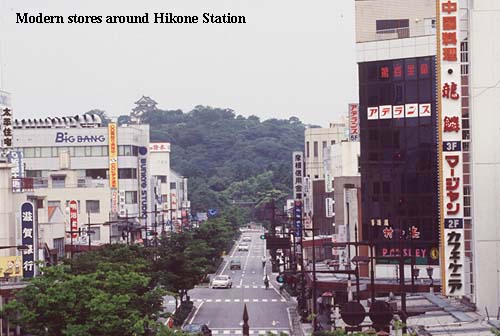

Since political authority of the daimyo had been officially removed in 1868, the ‘center’ of town life switched from the castle to the former chonin districts where economic and commercial activities still flourished. The most important district in this respect was Honmachi, and the wards alongside the main route connecting the castle with the Nakasendo highway. In 1889 this situation changed when the Tokaido railway line was constructed to link Tokyo with Osaka. The amount of road traffic along the Nakasendo rapidly diminished and, as with many other former castle towns, the focus of commercial activity shifted to the area in front of the new railway station. In order to facilitate this development a completely new road was built from the station to Hikone-cho, where it connected with the old through-road linking the northern and southern access routes to the Nakasendo. The latter road, in turn, has assumed less significance today, since the filling in of the outer moat created a much wider and straighter route through the SW-SE axis of the town.

In terms of area, the major land use in Hikone today is ‘residential’. More than half of the residential blocks contain new houses, however, so that it is now rather difficult to identify differences in character between former samurai and chonin areas. Despite this, contrasts can be drawn between the former daimyo’s residence, which has been reconstructed on the original site and partially converted to a museum, and at least one residence of a high ranking samurai which has been preserved in the ninomaru enclosure. Both residences are situated in walled compounds, which also include many smaller out-buildings.

Not surprisingly, the scale and grandeur of these residences differ markedly from the much smaller, densely packed, wooden houses which have been preserved in the former ashigaru wards. Typically, these are one and a half story structures which front directly onto the street, and which have a small garden at the rear. Rather larger traditional houses can be seen in parts of the old ‘inner’ town, indicating the higher status and greater wealth of the former residents here. Many of these houses are attached to out-buildings, including fire-proof storehouses (kura).

All the residential areas in the old sections of the town are characterized by narrow streets, usually without any pavements. Dog-legged streets are a common feature, and, since these were designed to hinder the approach of enemy forces through the town, they pose a difficult obstacle to the smooth flow of modern traffic. It is possibly for this reason that many former chonin areas have not developed as commercial centers in the modern town, but have remained exclusively residential.

The wealthiest of the former chonin wards was Honmachi, located along the main approach to the castle, adjacent to the second moat. Honmachi still retains commercial and retail functions today, but the relative importance of the area has diminished considerably. This is due, no doubt, to the change of function of the castle itself, and a decline in the amount of traffic using the old approach road. In contrast, the area of former craftsman wards along the old route connecting Hikone with the Nakasendo highway flourishes today as a small market and retail center. Of course, most, if not all signs of the former activities here have disappeared (e.g., sword smiths, oil sellers etc.), and the modern vista is of glass-paned shop fronts which line each side of the street under a semi-covered arcade. The continued commercial success of this street is probably accounted for by the fact that this was the major route for through traffic in the town until comparatively recent years.