Although closely akin to their Asian neighbors in both physical appearance and cultural background, many Japanese today maintain a strong belief in the unique identity of the Japanese race. Perhaps the strongest argument in support of this notion is the fact that the Japanese language (excluding imported words – mainly from China) has no close affinity to any other spoken language anywhere. It is also argued that the way the Japanese have shaped and molded their landscape, although strongly influenced by external cultures, is unique to the Japanese isles.

Recent archaeological evidence suggests man (homo erectus) was present on what today constitutes the Japanese archipelago during the early Paleolithic period, some 370 thousand years ago. Links have been established between the earliest known Japanese artifacts and those discovered in China dating from a similar period. Finds dating from the mid and late Paleolithic periods are well represented throughout Japan, and indeed for all later periods. Correlation between artifacts found in Japan and at various sites on the Asian continent leave little doubt that these nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers migrated to Japan from areas in both north and south Asia, often across land bridges which existed during cold ‘Ice-age’ periods.

Distinct cultural changes have been identified which may be linked to the introduction of new technologies and to the gradual displacement of homo erectus by homo sapiens and, more significantly, of homo sapiens by modern man (homo sapiens sapiens) some 30 thousand years ago. It is of interest that these displacements have been linked to climatic and environmental changes, indicating the role the surrounding landscape plays in ultimately shaping the destiny of modern man. The end of the Paleolithic (Mesolithic) era in Japan also coincides with climatic change at the end of the last glacial era, about 13 thousand years ago. A warmer and more humid climate led to food surpluses and thus to a more sedentary lifestyle. It is intriguing that the oldest known pottery has been discovered in Japan, suggesting the possibility that the ‘Japanese’ at this time were inspiring cultural transformation and thus already identifiable as a distinct cultural group. All other evidence points to the contrary, however, suggesting that groups now identified with the emerging Jomon culture claimed their origins in Siberia or southern China.

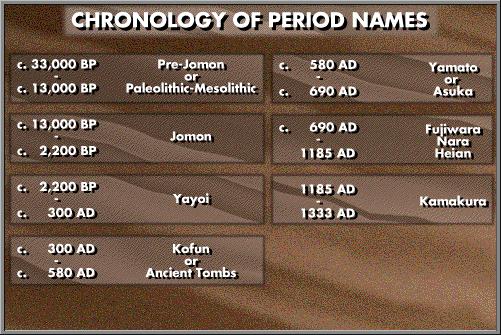

Early history is divided into three distinct cultures, the Jomon, Yayoi and Yamato. Jomon culture ran from roughly 10,000BC to 300BC. It possessed a simple form of pottery technology and rudimentary agriculture, being mainly a hunting culture. Yayoi culture (300BC-300AD) was noted for its more decorative pottery, rice cultivation, and more complex technology. The Yamato culture is identifiably Japanese. It begins with the Tomb culture (Kofun culture which is noted for the large tombs built for the aristocracy, and this merges into the early Japanese state at Nara.

The ethnic connections between these three main cultures are not clear. Neither is it clear how much of an input there has been from continental sources, mainly Korea and China. That there is input is undeniable, but it is impossible to say conclusively that, for example, the Yamato or Yayoi culture represent a new group of migrants who brought with them a new genetic pool and continental culture from which the Japanese of today are descended.

Sites identified with Jomon culture have been identified throughout the Japanese isles, and include the earliest known settlements in Japan. Jomon culture is typified by distinctive pottery styles, and by the use of polished stone and bone implements. Primitive agriculture was almost certainly practiced by these people, together with hunting, gathering, and fishing. The suggestion that these people shared a common culture should not imply that the different tribal groups necessarily shared a similar ethnic background, however. While some new technologies may have developed indigenously, others were probably introduced by migrant groups entering through both north and south Japan. Trade and other contacts between groups undoubtedly encouraged the diffusion of new innovations, evidence for this being provided in the distribution of valuable minerals such as obsidian.

Jomon culture evolved slowly in this manner over a period spanning thousands of years. By contrast, the displacement of Jomon by the Yayoi culture took just a few centuries at most, beginning about 2500 years ago. The main innovations include the simultaneous introduction of bronze and iron artifacts, the development of rice cultivation, and the necessary reorganization of social groupings to allow efficient rice farming. The impact of these revolutionary developments on the landscape was considerable, and can be traced as a ‘wave’ of change moving from southwest Japan (Kyushu island) to the northeast (Tohoku) region. Almost certainly these innovations originated in China and were introduced to Japan via the Korean peninsula. The speed of adoption of the new culture, and the survival of an assortment of metal weaponry from this period suggest that assimilation may have been forced by arms rather than by more peaceful means. The question of whether force was used by groups of immigrant invaders, or by indigenous groups who were first to acquire the new technologies requires further research, however, although the answer is clearly crucial to a full understanding of the origins of the Japanese people.

Documentary and archaeological evidence confirm that Korean and Chinese influence remained strong during the period from the third century when the clan groups across Japan were gradually consolidated under the leadership of the Yamato. Possibly originating in north Kyushu, the Yamato clan had by the 5th century established themselves in the Nara basin to secure a more central power base. Whether their ancestry was traced to pre-Yayoi Japan, or to Korea, or elsewhere on the continent, the Yamato rulers claimed imperial status and established a line of Emperors which continues today. On this basis alone perhaps, the Yamato and contemporary clan groups can claim to have been representative of the ‘Japanese people’.

In order to consolidate and perhaps legitimize their reign, the Yamato rulers encouraged the adoption of Buddhism from the sixth century. With the new religion came, amongst other things, the introduction of a writing system so that now, for the first time, the Japanese could record their own history. Early documents reveal how, during the period from the 7th to 9th centuries, the frontier of ‘Japanese’ rule was pushed northwards to reach Hokkaido. There, the ‘barbarians’ were allowed to remain in relative peace until the 19th century. Today, the Ainu people who remain in Hokkaido are recognized as the only indigenous minority group with ‘non-Japanese’ origins. Even today much speculation exists concerning the precise origins of these people, and it is even suggested that they may represent a survival from the Jomon period.

The second largest minority group in Japan today comprises people of Korean ancestry. While it is true that most are or claim descent from people who were forcibly brought to Japan after the annexation of Korea in 1910, it should not be forgotten that at the time when Buddhism was first introduced to Japan many thousands of people from the Korean peninsula were invited to the Japanese Imperial court to bring with them new skills and technologies. Without doubt, many of these people were later assimilated into the ‘Japanese race’. As a rigid social hierarchy evolved during the 16th and 17th centuries, however, it may be that some people unable to lay claim to Japanese ancestry found themselves classed as ‘non-humans’, along with criminals and other outcasts. The descendants of these people form another larger minority group who are still the subject of widespread unofficial discrimination. Perhaps as a result of such discrimination, it is of interest to note that these burakumin, as well as the other minority groups, have all contributed to the structuring of Japanese society as we know it today.