In 1841 Tsumago had a population of just 418 people, living in 83 households of which 31 were inns. The town was relatively small compared to others on the Nakasendo and, given its remote location at the southern end of the Kiso Valley, seems to have been an obscure place of no special note.

Today the situation is very different. As a tourist destination Tsumago is arguably the most popular of all the post-towns on the Nakasendo, and pictures of the charming, ‘authentic’ Edo main street are well-known throughout Japan. This street is packed with visitors during daylight hours and, in the evenings, the many inns on either side come alive with the sounds of merriment and revelry behind softly illuminated shutters and screens.

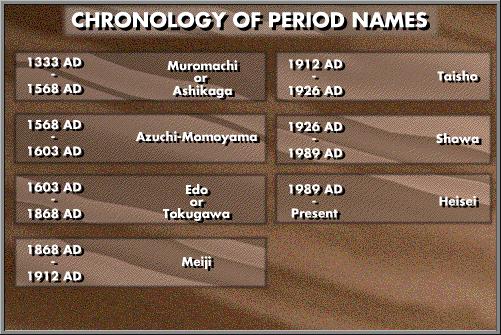

The modern success of Tsumago stems partly from the fact that it always had been a remote and obscure town. No modern buildings intruded during the economic boom of the sixties, perhaps because the lack of a railway station meant the boom never echoed here. The town fathers were blessed with foresight, however, and they recognized that the decrepit, tumble-down inns of a long forgotten Tsumago could be rejuvenated to attract city people with an interest in bygone eras. After all, relics of the Edo period had long since disappeared from the streets of downtown Tokyo.

A decision was made to ban the installation of above-ground electric and telephone lines, and other on-street modern intrusions such as vending machines from the old quarters of the town. Perhaps unnoticed by many tourists today, it is this policy which distinguishes Tsumago from the vast majority of other historic locations in Japan, and which helps make the town so photogenic. As an added touch, the postman is required to wear traditional Edo period costume.

This careful preservation of the post-town flavor now draws in bus-loads of tourists throughout the year. The noise and bustle of so many people along the main street does itself help to recreate the atmosphere of a busy post-town, but one cannot help wonder the degree of artificiality of this facade. Whatever one’s feelings on the matter, there is no doubt the income generated by such activity has enabled the restoration and even rebuilding of many period structures. These include the original waki-honjin, which boasts a toilet once used by the Emperor Meiji, and a rebuilding of the honjin itself on the original site. The former building, made famous in Shimazaki Toson’s novel Before the Dawn was destroyed by fire many years ago and the reconstruction is due for completion in 1995.

Leaving the town at the location of the old “kosatsuba” (official proclamation board) the old highway ascends steeply up the valley side to the site of Tsumago castle. The castle was to defend the southern approaches to the Kiso valley during Warring States period, but was dismantled in 1615. From the summit of the hill on which the castle perched, excellent views can be obtained along the length of the Kiso valley.

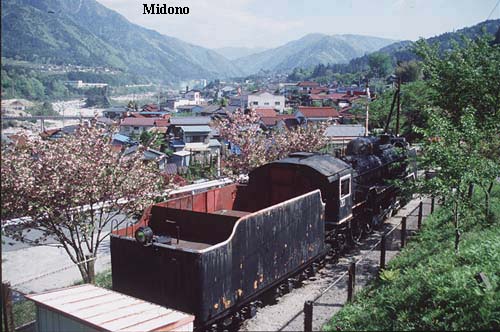

The road now meanders through a mixture of forest and farmland, and is one of the most scenic stretches of the whole journey. The three and a half mile section between Tsumago and Midono is popular with walkers today because it gives easy access between Tsumago and the nearest train station, Nagiso. Midono, the old post-town, is slightly higher up the valley than Nagiso with its station, souvenir shops, supermarkets, and modern highway.