With a population of just over 52,000 today, the city of Suwa is the largest the old Nakasendo passes through in modern Naganoprefecture. Much of the appeal of Suwa derives from its many tourist attractions, including the twin shrines of ‘autumn’ and ‘spring’, the numerous hot springs in the area, and the amenities and scenic beauty of Lake Suwa itself. Indeed these were the very same attractions which made Shimo-Suwa (Lower Suwa) a popular place to stop at in the Edo period. Additionally, the town stood at the junction with the Koshu-kaido, another of the ‘Five Highways’ and an alternative route to Edo. Even in 1843 the town boasted a population of more than 1300, and 40 inns for ordinary travelers, while a further 900 people and fourteen inns occupied neighboring Kami-Suwa (Upper Suwa) – the first official post-town on the Koshu-kaido.

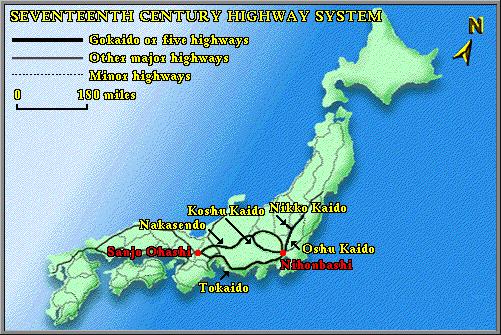

17th century Highway System

The best preserved part of the old town today is at the junction of the two highways, opposite the site of the old honjin.

Tourists are still served by a number of inns which survive from the Edo period, but gone unfortunately is the public hot-spring and open sided bath-house which used to serve travelers here in the past. Nearby, however, is Shimo-Suwa autumn shrine. Surrounded by giant Japanese cryptomeria, this ‘home’ of one of the founding deities of the Japanese (Yamato) state is well worth a visit.

Leaving Shimo-Suwa the road makes a steady ascent up a valley which leads eventually to Wada-toge, the highest of all the passes on the Nakasendo. The old and modern highways intertwine to such an extent that tracing the original route sometimes proves very difficult. At one point the old route becomes a grassed-over track way, running just a few feet below the modern highway. The route is blocked, however, by farmers who have dug over the old road for vegetable plots and rice fields and, more recently, by a junk dealer who uses the land as a scrap yard for old cars.

After three and a half miles a stone monument is reached, dedicated to the memory of six anti-shogunate samurai who fell in a battle here with loyalist troops in 1868, at the time of the Meiji Restoration. Beyond this the modern road is rejoined for a while, as the climb up the pass steepens. At the point where the modern road begins to twist in a series of hairpin bends – a feature rarely seen on the old highway – the original route can be rediscovered by climbing the steep concrete road embankment. For the next mile or so the route becomes a flower strewn path through peaceful woodland, until reaching an ichirizuka next to the site of a former teahouse. This was the last opportunity for travelers in the past to find refreshment before the steep and rocky one and a half mile climb to the summit.

The modern road is rejoined at this point, before it disappears into a tunnel which takes traffic under the pass. For travelers of the old Nakasendo, this was also the point where horses had to be dismounted and baggage unloaded, for the way was too steep even for them. If it was winter the pass might often be covered in snow, and porters would don special clothing to resume the journey. Straw boots would be worn, woven in such a way that the feet kept warm even when the boots were wet. On the bottom of the boots three-inch triangular metal spikes were sometimes fitted to keep a grip on the path. Alternatively, snow drifts could be crossed by wearing snowshoes made from wisteria, and with thorns attached to the underside for grip. After an arduous climb, and at a height of 5300 feet, the pass was eventually reached.

Wade-toge