The route over Usui-toge is one of the oldest on the Nakasendo, having originally formed part of the 8th century Tosando highway. Since the final section of this route is also the steepest, and probably most difficult to travel on the whole journey it is no surprise that Sakamoto boasts a history as a post-town which also dates back to these early years.

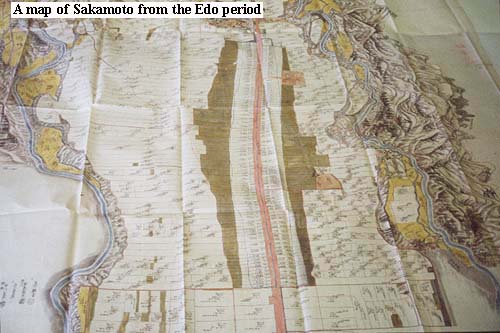

According to evidence from maps of the Edo period, however, the layout of the town was completely remodelled when its post-town status was confirmed by Tokugawa Ieyasu in the early 1600s. Land behind each inn and other houses was reallocated according to the status of the establishment. On the main street the buildings shared a common frontage, separated from each other only by slightly protuding fire-proof walls. The street itself appears to have been widened so that the drainage ditch could be re-aligned down its center. This is one of the features which was still clearly visible in Hiroshige’s day.

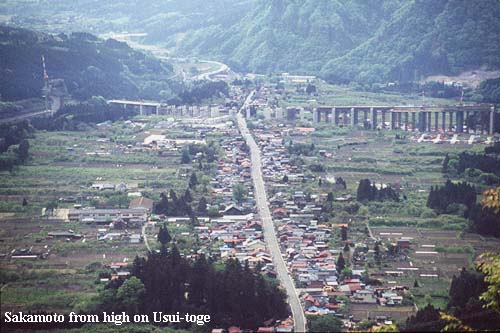

It is quite possible that other post-towns on the Nakasendo were rebuilt in similar fashion at the time when the route of the Nakasendo was fixed in 1602. What may have distinguished Sakamoto was its comparatively large size, since the town had two “honjin”, two“waki-honjin” and forty inns. This was due not only to the proximity of the difficult pass but also, on the other side of the town, to the fact that Usui barrier station (one of the two most important checkpoints on the Nakasendo) was located nearby. Looking at the town today it appears an almost insignificant place. The truth is that many Edo period buildings have survived, including some original inn signs, and that the layout is virtually unchanged from that of those Edo period maps.

As at other major passes through the central mountains, many modern rail and roadways tend to converge along the valley floor which leads to the pass. Leaving Sakamoto, however, the old Nakasendo manages to avoid these modern intrusions and the walking is generally along quiet country lanes.

Usui

After a short while the site of the old barrier station is passed on the left, now marked only by a stone platform and one of the barrier gates. On the right, soon after, is Yobugawa rail station. Although only very small, even the big Nagano-bound express trains have to make a ten minute stop here as they are coupled up to an extra engine to take them up the incline which runs under Usui-toge. A thriving and well-known local trade has developed because of this, involving hot noodle sellers who pass food through the train windows to waiting passengers.

During the six mile stretch to the next post-town, Matsuida, the old route keeps high up on the terrace above the valley floor, and generally well away from modern traffic. The mountain landscape for which the Nakasendo was so famous gradually recedes behind as the Kanto plain is approached. Many other features of the old highway are still evident, however, including a paticularly fine group of Jizo statues (offering protection to travelers) who stand on a large, and very solid, stone boulder. By tapping the boulder with a smaller stone a resonant bell-like sound is produced. This only works when struck at a particular spot, but the marks made by thousands, if not millions of passing travelers through the ages leave no doubt where the right spot is.

Matsuida today has a rail station and the old main street is now alive with shoppers at the many small stores rather than itinerants seeking custom at inns. The change has been slow in coming, however, since it was only recently that the last inn was forced to close business for the last time. In the Edo period, with a population of just over one thousand in 1843, Matsuida thrived because of proximity to the Usui barrier, where travelers were forced to stop when the checkpoint was closed. Today it is the free movement of people, and a growing number of commuters in particular, which offers most hope for future prosperity.

Leaving Matsuida, it is a further six miles to the next post-town at Annaka. Apart from the first few hundred yards the old highway is by-passed by the modern road, although the two routes do run closely parallel. Even the old route is fairly busy with traffic along this section, however, a sure indication of the ever growing proximity and influence of Japan’s largest metropolis. But even this is forgotten during the approach into Annaka, as the road passes through a double row of mature cedar in Japanese, “namiki”. Considered one of the finest surviving avenues of its kind along the whole of the Nakasendo, these huge and very ancient trees dwarf all modern distractions.