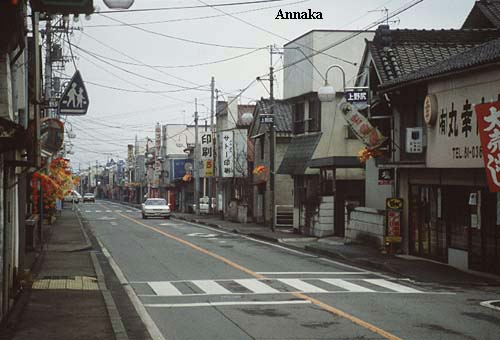

The small size of Annaka castle town is attested to by the small numbers of the merchants and artisans in 1843, living in the post-town quarters. In that year only 348 people are recorded (samurai and their families being exempt from census counts), living in 64 households, of which seventeen were inns. It seems that such close proximity to a daimyo and his retainers did not encourage too many travelers to spend a night here.

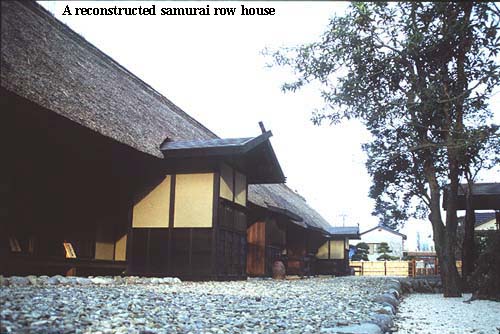

Modern stores have now replaced the inns and other old Edo period buildings, although a fine group of old samurai lodgings have been restored adjacent to the ‘castle’ site. Perhaps Annaka’s greatest legacy from the past, however, is the complete set of very detailed honjin records, now stored in public archives. Most such records were either thrown away whenhonjin lost their function in the Meiji period, or were destroyed by fire. It is from the Annaka records, which include financial accounts and descriptions of the number of porters hired for each major procession passing through, that we derive much of our knowledge today about the former administration and management of post-towns on the Nakasendo.

Travelers who did not wish to stop at Annaka had less than a mile to go before the next post-town, Itabana, was reached. This is the shortest distance between post-towns on the entire journey. The old route is slightly unusual in the sense that it was forced to cross the Usui River twice before arriving at Itabana. This double crossing was over a meander in the river which cut into the outer, northern bank so deeply that passage along it was impossible. Modern use of dynamite has today allowed this problem to be overcome. Surprisingly, since the distance between post-towns was so short, a tateba, or unofficial rest-stop, was established in the space between the river crossings. Not so surprisingly it was called Nakajuku – or ‘resting place in the middle’. It’s existence meant there was an almost continuous line of inns and tea houses from Annaka into Itabana.

Little remains today in Itabana to suggest what a lively and thriving place it once was. With a population of more than fourteen hundred in 1843 the town boasted as many as 54 inns. Like Oiwake and Fukaya the town had a reputation for an active nightlife, and the 1843 census records 82 meshimori-onna (serving women) and a further 107 ‘lesser wenches’, officially. No doubt much of this action was inspired by the fact that the two post-towns on either side, Annaka and Takasaki, were too closely under the watchful eye of shogunate officials, since they were both also castle towns. It may also be that the inhabitants of these towns, including a few off-duty samurai perhaps, would themselves patronize the inns at Itabana, away from the watchful eyes of their superiors.

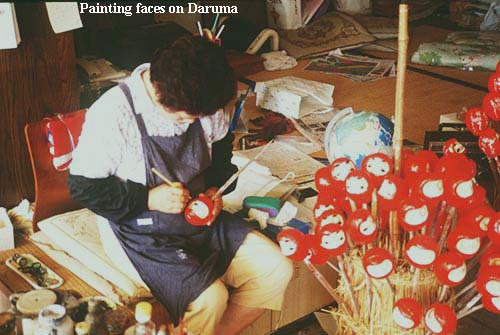

The next three and a half mile stage into Takasaki passes along a mixture of busy modern highway and quiet old backstreets. Atop a hill to the right, on the far side of the river, is an ancient Zen Buddhist temple dedicated to the Indian priest Bodhidharma, or Daruma as he is known in Japanese. Familiarly recognized as the ‘roly-poly doll with no legs’, images of Daruma are purchased to bring good fortune to new projects. Many small workshops in this area thus specialize in the production and painting of papier-mache Daruma dolls, and the unique style and brilliant red color of the Takasaki Daruma has made them famous throughout Japan.