The Nakasendo is a highway which connected Kyoto and Edo (now called Tokyo) over an inland route that passed 500 kilometers (310 miles) through the heart of Japan’s main island of Honshu. From Kyoto, it passed along Lake Biwa, over the mountains at Sekigahara, across the plains north of present-day Nagoya, close to the southern Japanese Alps, across the plain between Matsumoto and Karuisawa, and down to the Kanto plain which surrounds present-day Tokyo to Tokyo’s predecessor, Edo.

It was established around the 8th Century as one of several highways centering on Japan’s home provinces around the ancient capital of Nara. At that time, it served to knit the growing Japanese state together. While it succeeded in doing this to some extent, it was not until the Edo period (1600–1868) that that Nakasendo reached the peak of its development, but by this time, the political center had shifted to Edo at the opposite end of the road.

Edward Stokes quoted an Australian writer who said, “A historian needs a good pair of boots.” This would be no surprise if said of a geologist or an archeologist, but historians usually are perceived as requiring leather patches on their jacket elbows to avoid wearing holes in their sport coats by leaning over dusty documents spread across a library desk. Marching long distances is not the normal historian’s job. However, whether the Nakasendo highway is studied from a historical perspective, a geographical perspective, or a social or political perspective, the very best way to study it is to walk it. Walking along brings the highway’s student in contact with many unanticipated aspects of the highway. It also draws the student into old villages with unique inns, each of which houses people, history and experiences that are immensely satisfying to come into contact with.

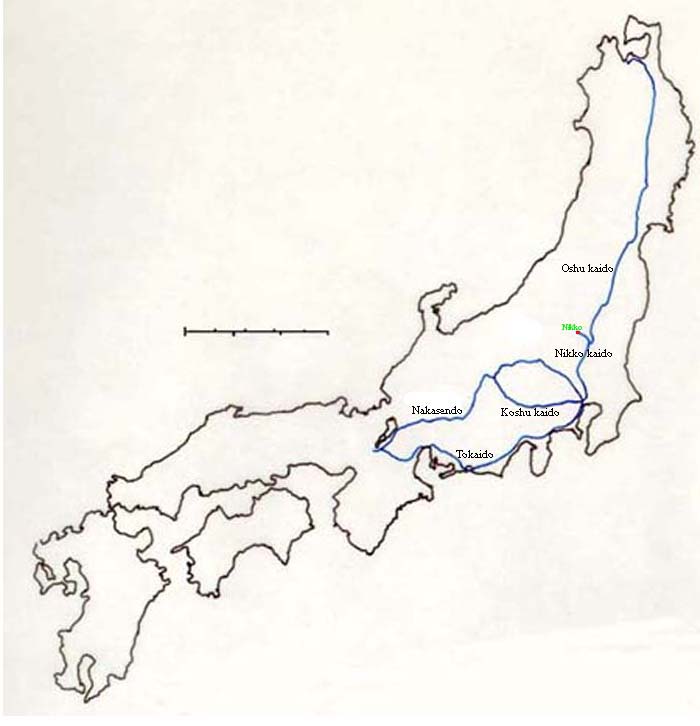

Map of central Japan showing the Nakasendo and the Tokaido highways.

In the early years of the 17th Century, Japan was united under the feudal leadership of the Tokugawa family which had its headquarters in Edo, some 500 kilometers east and north of the capital region around Kyoto. The Edo regime or shogunate (named after the leader’s title, “shogun”) moved quickly after the last battle of national unification at Sekigahara to establish a communication system which would allow the regime to move quickly and efficiently messages, personnel, diplomatic missions, spies, and important goods to or from Edo throughout the empire. Five highways including the Nakasendo were designated for this purpose. Of the five, the Tokaido was the largest and busiest and has remained the most famous, but the Nakasendo survives today in a form that travellers in the seventeenth century would still recognize.

Each highway was organized along principles which the Chinese used to regulate their highways in imperial times. The route was carefully laid out, the width of the highway was determined, and villages at convenient intervals along the way were designated as post-towns which were responsible for the functioning of the highway in the area and for providing food and lodging for official travellers. Since the burdens of being a post-town were great, nearby villages were also ordered to provide support to the post-towns when required: additional labor, horses, food, and utensils could be called for from these sukego villages.

In a short time, this communication system took on additional roles. Originally limited to the transfer of official business only, the Nakasendo and other highways soon found that the 250-year peace which followed the battle of Sekigahara permitted and encouraged unofficial traffic. Osaka, the country’s commercial center, and Kyoto, a manufacturing and cultural center, each with about 400,000 people, lay at the western end of the Nakasendo while Edo, the political center which probably had a population of a million people by the early 1700s, lay at the eastern end. Transport agencies found their services in such demand to transport people, information and, to a lesser extent, goods from one end to the other that they were encouraged to offer express service which guaranteed delivery in as little as three days. Although this goal was ambitious, regular service in five days was standard.

In the second half of the Edo period, pilgrimage became increasingly popular. Travel for the sake of travel was not allowed, but religious travel was permitted. As time went on, various religious establishments, like Ise Shrine which was dedicated to worship Amaterasu, the sun goddess, popularized pilgrimage. Meanwhile, the economy grew vigorously, giving more people enough money and leisure to travel. Soon there were thousands of pilgrims on the highways.

Not everyone could travel, of course, so literary figures and artists were hired to write about or picture travel. Soon, travel literature was popular while Hiroshige and other famous woodblock print artists were commissioned to document their own travels in print. Hiroshige made his name in this genre with his series “53 Stations of the Tokaido” among others.

In the case of the Nakasendo, an artist named Eisen was commissioned to commemorate the highway in woodblock prints. Because of bankruptcy and a fire in Edo (perhaps for the insurance money), Eisen absconded, leaving the project incomplete. Hiroshige was asked to finish the Nakasendo project. Their combined efforts produced the series “69 Stations of the Nakasendo” which document each of the highway’s 67 post-towns plus Kyoto and Edo. Many of these prints depict typical scenes in the post-towns while others portray famous points along the route.

Today, the Nakasendo is still with us. While the Tokaido has now been overlaid with modern highways and train lines to the extent that only a few stretches of the old road can be identified, the Nakasendo runs through areas of Japan that have been less transformed by economic growth and change. Thus, long stretches of the highway remain much the same now as two hundred years ago. Where modern roads have been laid on top of the original Nakasendo, they are often quiet one or two-lane country roads that see little traffic, instead of the massive highways over the Takaido.

Footnote

Edward Stokes, Hong Kong’s Wild Places: An Environmental Exploration, Oxford University Press (Hong Kong, Oxford, New York: 1995), p. xi.

Five Highways of the Edo Period.

Written by Thomas A. Stanley and R.T.A. Irving.