The current emperor, the Emperor Heisei, it is claimed, has an ancestry with origins in the Japanese pantheon. Tradition further proclaims that it was the father of the Gods, Izanagi, who thrust his spear into the waters of the earth and so created the Japanese isles from the droplets thus formed. Though most Japanese today discount such myth, there is no doubt that a strong link exists in the Japanese mind between the spiritual and natural worlds. The survival of Shinto in the modern age, and the reverence attached to natural features such as Mount Fuji, the sand bar at Amano Hashidate, and the blossom of cherry trees are testament to this.

The mosaic-like map of the surface geology of Japan reveals something of the tortuous processes by which the Japanese islands were, and are, being formed. Over the last 400 million years there have been four major periods of mountain building, each of which, notwithstanding the contrary effect of erosion, including glaciers, has contributed features to the present day Japanese landscape. The forces which power such mountain building processes are the same as those which account for continental drift. Sea floor spreading pushes oceanic plates into less dense continental plates at the continental margins. The denser oceanic plates are driven under the continental plates, and the resultant friction causes earthquakes and volcanic activity. Japan is located in an area where two oceanic plates collide with the Eurasian continental plate, on the so-called ‘ring of fire’. Deep trenches extend along the zones of plate-collision in a series of arcs off the east and south-eastern shores of Japan, forming the deepest maritime waters on earth. Above the zones of subduction the rocks at the continental margin are thrust up, fractured, and twisted. Magma is forced up through the fissures to create volcanoes on the earth’s surface. Active volcanoes are strung out in a line, known as the volcanic front, parallel to the ocean trenches. Thus, in general terms, the topography of Japan is characterized by a series of mountain ranges running longitudinally across the country. The volcanic front associated with the present mountain building process extends along the line of the Japan Sea coast, on the so-called ‘back-side’ of Japan.

About 80 percent of the land in Japan is considered ‘mountainous’. Although not particularly high, the hills and mountains of the Japanese interior are steep and are not, therefore, considered habitable or suitable for cultivation. The young rocks are eroded by many short, steep and fast-flowing streams and rivers, the longest of which tend to flow towards the Pacific Ocean. The largest plains are thus found along the Pacific coast, where eroded material is deposited as alluvium. With such a shortage of habitable living space and cultivable land, it is only natural that the largest plains, such as the Kanto Plain (Tokyo), should have the largest concentrations of population and industrial activity. With as many as 40 million people living in the Kanto region, however, representing one-third of the total population, it is no wonder that the human landscape appears so over-crowded in some parts of Japan, yet under-populated in others.

Japan is often described as a country lacking sufficient natural resources. This is true insofar as Japan is heavily dependent on the import of such commodities as oil, iron ore, and bauxite to keep her economy fueled, but hides the fact that there are many resources with which Japan is well endowed, and the exploitation of which has played a significant role in shaping the Japanese landscape.

Perhaps the most obvious landscape feature is the great extent to which Japan’s mountainous area is covered by forest. Species indigenous to Japan range from sub-tropical broad leaf evergreens in the south through temperate deciduous trees to sub-arctic needle leaf conifers in the north. Few areas of primary vegetation remain, however, because the Japanese have for centuries exploited their forest resources for fuel, building materials, and the manufacture of various items including paper. Even as late as 1960 eight percent of Japan’s total energy requirement was provided by firewood and charcoal, while virtually all homes were constructed of timber. Many villages in remote mountain districts depended almost entirely on forestry for their livelihoods, despite the difficulties brought about by the severe overcutting during the Pacific War. Most foresters cultivated small plots of deciduous trees, this being the most appropriate material for firewood and charcoal production, and for other items such as mine props and railway sleepers.

After 1960, however, demand for these items declined dramatically and foresters had to switch to cultivation of conifers, notably Japanese cedar and cypress, to meet the growing demand for construction materials and wood pulp. Although much faster growing than deciduous trees, it takes between 45 and 50 years for these conifers to reach maturity. While the mountain landscapes of Japan have been completely transformed by this switch, many mountain villages have suffered decline or complete abandonment during the period it takes for these trees to mature and Japan has become increasingly reliant on imported timber to meet domestic demand. By the early 1990s, barely 30 percent of Japan’s demand for timber products was produced locally.

Another industry with a centuries-old tradition is fishing. Japan lies at the juncture of two major ocean currents – the warm Kuroshio and the cold Oyashio – which provides a rich feeding and breeding ground for many species of fish. Fishermen operating from ports distributed throughout the country have exploited this to the extent that Japan is now one of the leading fishing nations in the world, landing over 14 million tonnes annually. Although much of this is exported, the huge domestic demand for fish is reflected in the large numbers of seafood restaurants found in every Japanese city.

Hydro-electric power generation

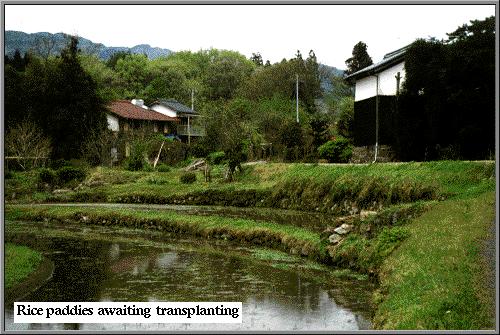

Inland waters provide another important resource. Farmers depend on the annual rains in late spring to flood the paddy fields for rice transplanting, and industrialists depend on the extraction of huge quantities of underground water for cooling purposes. Unfortunately, over extraction in recent decades has led to problems of land subsidence, causing damage to property and greatly increasing the risk of flooding. The fast flowing rivers of Japan are also used for hydro-electric power generation which presently provides about ten percent of the total energy requirement. In 1950, coal was the most important fuel for power generation and other energy needs. This was mined in northern Kyushu and in Hokkaido and it was the existence of these coalfields which attracted the first iron and steel works in Japan to be established nearby, at Yawata (1904) and Muroran respectively. However, the coal is of relatively poor quality and is difficult and expensive to mine. After 1950, therefore, Japan switched to imported oil as the main source of energy, and this continues to provide 75 per cent of the total energy requirement, although other sources of energy are being sought.

More than half the minerals with industrial uses are found in Japan. Unfortunately most occur in quantities too small, or are of insufficient quality to meet Japan’s needs. Japan is therefore heavily dependent on imported minerals for her industrial requirements, the most important example being iron ore. The impact of a high degree of dependency on these basic raw materials on the landscape is considerable. It means, necessarily, that Japanese heavy industry should have a coastal location with good access to deep water port facilities. This has resulted in the destruction of much of Japan’s natural coastline, and given rise to problems concerning pollution.

The forces shaping the Japanese landscape are many and varied and include natural as well as man-induced elements. With a total population of some 124 million living on the Japanese isles, the real challenge is to achieve and maintain a balance between these forces in future.