Like many Asian family systems, the Japanese family system was an extended family which included distant relatives as well as the dead. In the earliest times, and certainly with the influence of China, ancestor worship was a strong and vibrant belief which made deceased real, active members of the family. Noble families, and families of the warrior class, placed great value and importance on their ancestors. One of the problems of newly arisen aristocratic families was to ‘find’ sufficiently impressive ancestors who would justify contemporary importance.

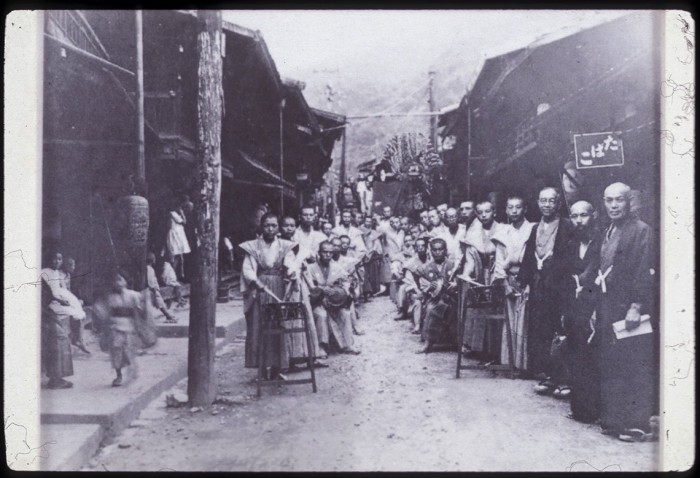

Ancestors continue to have significance today, a reflection of the importance of the family system itself. Buddhist belief holds that ancestors are able to exert influence over affairs in this world. The spirits of ancestors return to this world at Obon, a summertime festival of the dead. The spirits are fed and treated well to ensure their aid in the future and so that they do not linger after the three-day period and cause damage to the living. Obon is one of the two yearly festivals which bring distant relatives together, the other being New Year.

An extended family consisted at least of grandparents, parents and children in addition to ancestors. A main or stem family might have affiliated to it branch families. Each branch family at some time might itself, while maintaining its subordinate position to the main family, become the stem family to several branches. Thus, a well-established, well-organized, and rich family could become extremely large.

In addition to real familial relationships, families often adopted as “branch families” people who were not related by blood. This kind of branch family was often in an economically subordinate position: perhaps a family of farm workers who depended on the stem “family” for land and tools. The fictive familiar relationship added extra depth and strength to the economic relationship. Theoretically, an entire village might be one large extended family in this manner.

In fact, very few families were organized along the lines of the extended family. Simply put, few were rich enough to sustain or require such a complex system. For the majority of Japanese, even the three-generation family (grandparents, parents, and children) was more of a dream than a reality. Life expectancy was so short until recently that few lived long enough to see grandchildren; certainly few families experienced the pleasures of more than one grandparent until well after World War II when life expectancy reached eighty years.

Another difficulty in achieving the ideal extended family was conflict between the eldest son inheriting the family headship and the need to have an able person as head of the family. Who filled the position was crucial because the family head held absolute authority over the family’s property and its members; a series of wrong decisions could ruin everyone. Many a family chose to give the family headship to a younger but more able son; this threw into disarray the strict hierarchy of the ideal. Furthermore, many younger sons strove to prove their ability; in the case of samurai families in tumultuous times, this might mean that a younger son killed his less able elder brother in order to become family head.

Yet another difficulty was that some families did not produce a son or an able son. In such cases, it was common for a son to be adopted. In some cases, a daughter might be adopted and then her eventual husband would be adopted as son and heir. A full chart of almost any family would reveal adoptions which have maintained the family name, but not necessarily the blood line.

Family is particularly important in many trades or craft industries where skills are passed down from generation to generation. The familial relationship helps maintain the continuity of a business entity.

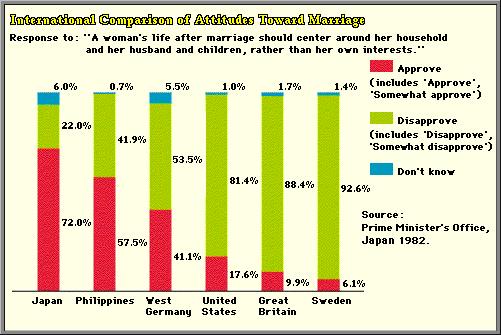

In the modern period many factors have worked against continuity of this family system, although attitudes toward marriage still follow an essentially traditional pattern. As in most modern economies, the average number of children in each family has steadily decreased and now stands at less than two. Family continuity becomes more difficult, raising the possibility of greater reliance on adoption.

The high cost of housing and small size of dwellings makes it virtually impossible to house more than the nuclear family under one roof. Modern values which emphasize independence and self-interest make children less willing to have grandparents live with them while housing aimed at retired people encourages the older generation to maintain separate homes. Generational conflict has steadily risen and driven wedges into the three-generation family while salaries give each nuclear family a life separate from relatives both close and distant. The distance between generations has risen to such a degree that at least one company does a large business renting actors who play children or grandchildren to lonely elderly people who nostalgically pine for the large, close-knit, extended family of yesteryear.