Edo Period

The Edo period economy has been hotly debated for years and views of it have radically changed. When the political system was perceived as an unchanging, authoritarian, conservative feudal one throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the economy was supposed to be very much the same. That is to say, it was stifled by the oppressive political system. Failing to grow for a hundred and fifty years, the urban economy became profligate and the rural economy impoverished. Governments could not achieve balanced budgets leading to fiscal disaster whenever natural disaster struck. Worse yet, the governments of the shogun and daimyo habitually forced merchants to ‘loan’ money to them, but never paid it back thereby hindering the growth of the merchant class. For peasants, there was nothing but grinding poverty, hard work in the rice fields, and a short life span.

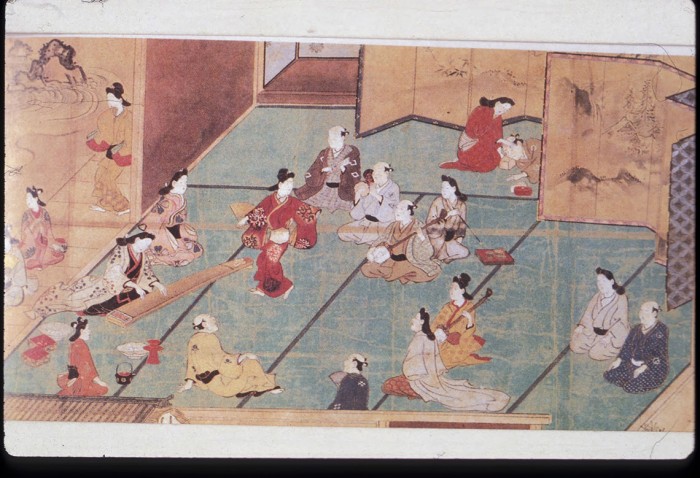

The first half of the Edo period had been quite different. Just like the government system which grew to perfection, the economy also grew and changed. The benefits of peace and the growth of urban centers around castle towns stimulated economic growth, especially in the larger cities like Edo, Kyoto and Osaka. Stories of immense wealth being accumulated abound until the Genroku era (1688-1703). At this point, the pace of both political and economic change slowed. The samurai class, it was argued, sought to preserve the political status quo by suppressing any further growth in the economy. The merchant class and commoners dwelling in the cities were increasingly drawn toward ornate lifestyles which dissipated wealth and energy. Kabuki plays attracted commoners to the entertainment quarters where tea, poetry, wine, and women soaked up capital which should have been invested wisely.

With this view of the Edo period economy, the ability of the Meiji period leaders to build up a modern state with a vibrant economy which could sustain a military machine capable of fighting and beating imperial Russia in 1905 was the first Japanese economic miracle. In fact, economists began to question where the capital for this miracle came from if both government and economy were as impoverished as thought; the number and amount of foreign loans in the period were negligible. New studies of the Edo period were undertaken and they began to show that although slow growth may have been the rule in the large urban centers, in the smaller cities and in many rural districts the economy continued to change and grow throughout the Edo period. Along the Nakasendo, for example, the Omi merchants stimulated commercial agriculture and rural industry. By the end of the Edo period, supposedly impoverished post-towns like Magome in the Kiso valley supported families that were quite well off: the Meiji period novelist Shimazaki Toson’s father was rich enough to travel all the way to Edo and Yokohama more to see what was happening with the foreign merchants than to transact any business. According to the new interpretations of the Edo economy, it was this kind of growth which formed a firm foundation for the development of the Meiji period.

1868-1945

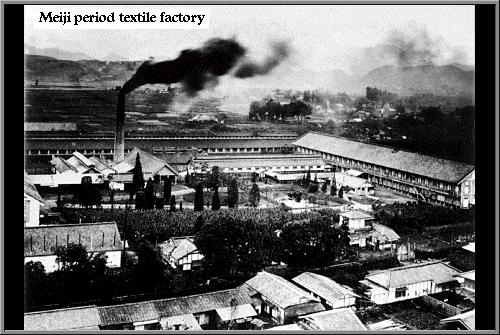

The Meiji period saw the new government pour its resources almost exclusively into things modern, including the economy. Initially, the government invested in businesses, but many of them failed to prosper and by 1881 most were sold at a loss to businessmen. Once these early losses were written off, however, the remaining businesses, no longer burdened by debt, eventually became profitable. The main role of the government was to promote modern business and industry by establishing legal frameworks (like the limited liability stock company) which protected modern economic growth. The government also helped by establishing standards, especially for export industries, and a banking system which channeled money into industry. Throughout the period, the new industries of the modern period and the old, traditional industries complemented and benefited each other.

old textile factories

At the end of the 19th century, the government began a series of policies which slowly introduced shifts into the economy. The most successful industries had been labor-intensive, low-technology and low-capital ones like textiles. These were very successful, especially as exporters, earning valuable foreign exchange which was needed to pay for capital goods which Japan could not produce. The government’s new policies were designed to force the growth of heavier industries which would demand more capital and technology and a work force with better skills. The risks were great, but the value added on and the profits might also be high.

Some of the new government policies included subsidies and protection for high-risk industries. Ship-building was subsidized beginning in the 1890s, for example. The intention was to build up a larger transport industry, taking business away from foreign companies, while encouraging the machine industry and the iron and steel industries which supplied the ship builders. Concurrently, the government built an integrated iron and steel foundry to move Japan toward independence in this area.

These policies met with mixed success until World War I in which Japan fought on the side of the Allies. Suddenly, foreign countries were willing to purchase nearly anything Japanese industry could produce. In addition, they had difficulty filling Japanese orders for capital goods. In both cases, Japanese industries found themselves faced with inexhaustible demand abroad and at home. Prices rose with demand and a level of prosperity previously undreamed of developed. The average dividend on stocks rose as high as 35% for the half year during the war. By the end of the war, all the risky investments of the late Meiji period were made good several times over.

The next fifteen years were not very good for the economy as a whole. The well-financed, high-technology industries which had been gathering strength continued to do so. Their sector of the economy generally grew at a rate of around 5% throughout the period. The traditional industries, such as those which made cloth for Japanese-style clothing, experienced difficulty. More and more people were turning to Western clothes and the cloth for Western clothes could not be made by the traditional industries. Competition between the modern and traditional manufacturing sectors set in and the modern sector had the better of the contest. The agricultural sector performed the poorest. Technology and productivity did not change very much and rice imports from Taiwan and Korea undermined prices. Throughout the period, the government continued its basic policy of encouraging and promoting growth in the modern sector of the economy, especially in heavy industry.

Although there was rapid growth in the modern sector, the number of people employed did not rise as quickly. The majority of the people were employed in agriculture and most of the remainder were in the traditional sector. Their incomes changed very slowly, creating a great deal of discontent. When the Great Depression struck in the early 1930s, the Japanese economy went into a sharper depression than the other industrial economies experienced. Stories of suffering, starvation, and of farmers selling their daughters into prostitution abound.

Unlike the rest of the industrialized countries, Japan came out of the depression very quickly. During the decade of the 1930s, private and public investment in industry, especially heavy industry continued and accelerated. More and more of the production began to be demanded by the military which was concerned about future wars and was coming to dominate government. The takeover of Manchuria in 1931, outbreak of war with China in 1937 and large-scale border clashes with the USSR lent credence to the military’s concern with increased heavy industrial production which could support the armament industry. By the end of the decade, growth rates of 8-10% were seen, but not in agriculture which continued to provide employment for half the population.

The war years, 1937 to 1945, saw the drive toward heavy industrial investment and development pushed to the extreme. Much of it was probably not wise: for example, industrial capacity was not increased in the late 1930s as much as the ferocity and length of war from 1941-1945 was to demand. Of course, in the end, it was all quickly destroyed in 1944 and 1945 when American bombers attacked.

After 1945

If the economy was devastated by war and defeat, the economic policies of the Allied Occupation were little help. The initial course was to strip the economy of the capacity to support a war machine. Factories and machinery were stripped out and shipped abroad as war reparations. The Japanese government pressed for policies which would revive the industrial economy without success until the Occupation began to modify the economic policies in 1948 in response to the rise of the Cold War internationally and resistance in America to subsidizing Japan’s economic existence (some $1.5 billion was pumped into Japan in the fist years of the Occupation, yet the entire gross national product was only $1.3 billion in 1946). Finally, steps were taken to rationalize and stimulate the economy and by 1954 the GNP finally reached the level it had been twenty years earlier.

The Occupation had taken other steps to improve the economy. It had broken up some of the largest corporations (Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo and Yasuda in particular) in order to increase competition and ‘democratize’ the economy. It had also redistributed farm land so that tenant farmers gained ownership of the land and with it an intense interest in improving agriculture. Later on, subsidies in the form of guaranteed prices for rice brought long term stability and growth to the rural sector.

Throughout the second part of the Occupation period and after, the Japanese government pursued policies similar to those of the prewar period: stimulate and protect heavy industry as the leading sector of the economy. The benefits of growth here would eventually spread into the service sector, traditional manufacturing and agriculture.

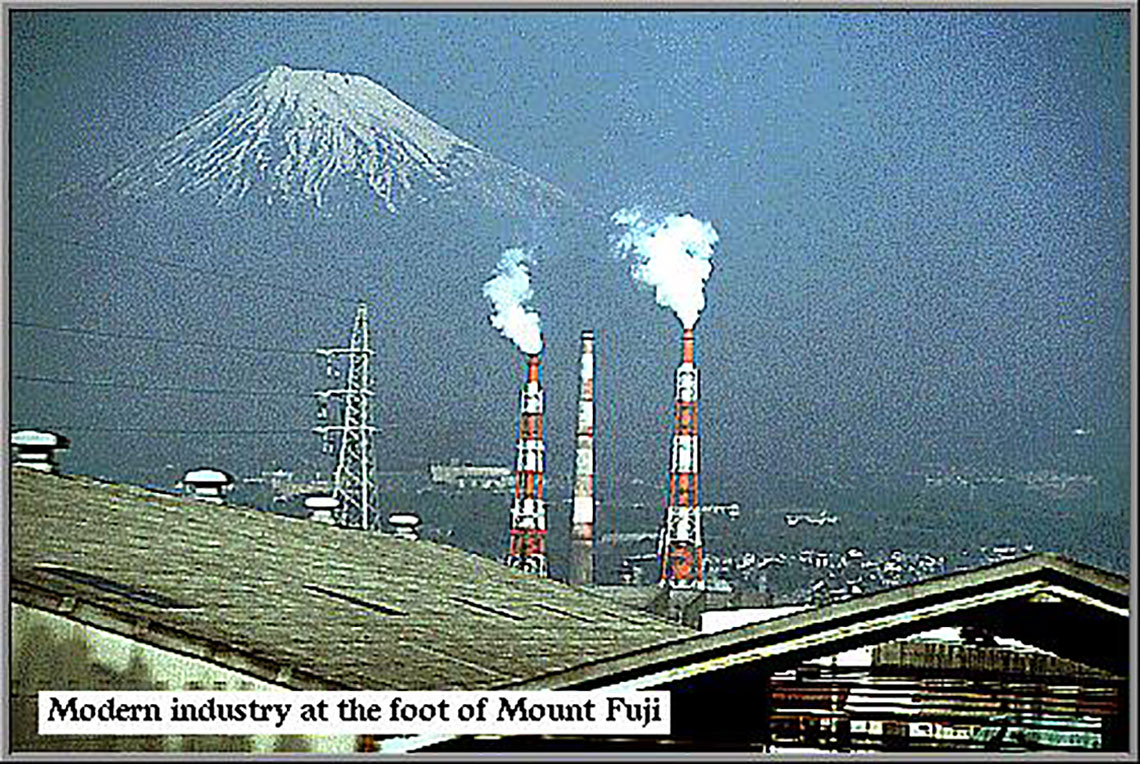

A combination of guided investment, encouragement of export industries, careful quality control, productivity increases, protection, and technology imports yielded results which came to be called the Japanese economic miracle in the 1950s and 1960s with annual growth rates consistently above 10%. By the mid-1960s, Japan began to join the major international economic organizations such as General Agreement on Trade and Tarries (GATT) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). To do so, the many barriers and tariffs which had protected the economy began to be dismantled, a process which continued over the next decades.

The process of opening up the economy has not been smooth and it has received much criticism, especially in recent years when Japanese trade surpluses with the industrial world have been large. Much of the criticism focuses on non-official barriers such as an archaic and complex distribution which inhibits penetration or a tradition of loyalty between companies which makes it difficult for a new company, especially a foreign one, to make a sale. These may all be gradually changing, but the process is very slow and frustrating to the many foreign businessmen in Japan and their governments.

Recent developments

A number of recent developments are interesting to note. One is that with the growth of Japan as an international economy more and more Japanese businessmen and their families are being posted abroad. They bring back to Japan perceptions, interests, experiences and abilities which are new and different, yet increasingly common as their numbers increase. One must wonder what sort of impact this kind of intimate contact with the outside will have in the future.

Another is the relationship between urban and rural Japan. In terms of income, there is little difference; if anything, rural families have had slightly higher incomes for some time because most households combine farming with non-agricultural work. Yet everyone perceives the cities to be where the opportunities are greatest and the quality of life higher. Rural depopulation is a continuing problem which has not been solved. In addition to centrally generated programs, the government has even presented each rural village with a substantial amount of money (about US$800,000) and left it to the village to use the money to try to stem the decay. Aside from rice, most of what Japan consumes is imported from abroad. What then is the future role of agriculture?

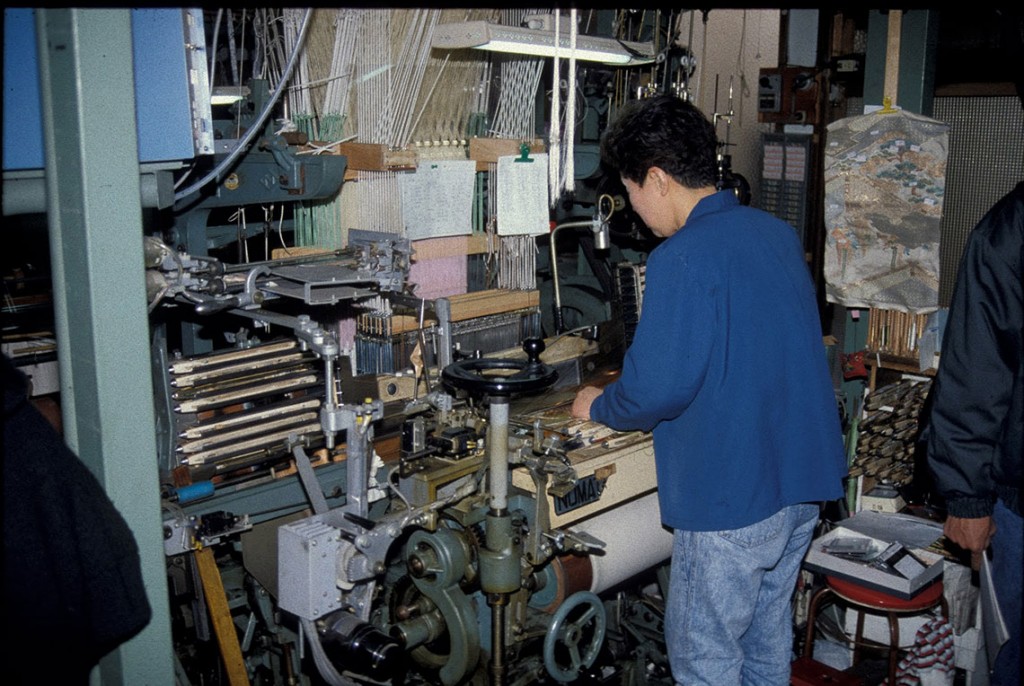

As the economy has become prosperous, the type of work which Japanese want to do has changed too. The young middle or high school graduates who gushed out of rural districts in the 1950s and took jobs in construction are now parents of children with university degrees. They would not think of taking on such work. Labor intensive industries must either move abroad, especially to Asian nations with lower labor costs, or bring in foreign workers to do the jobs. The one solution causes economic growth abroad and structural change at home; the other introduces social problems which few are willing to confront.

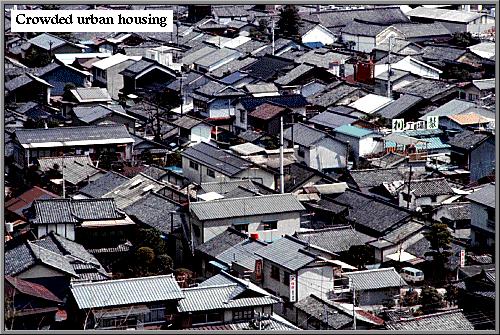

shortage of habitable living space

The concentration of industry and population in urban areas has caused increases in land prices which, in the 1980s, were stupendous. Young people found prices too high to dream of home purchase while those who inherited their parents’ home found the tax bill so high that the inheritance had to be sold.

In 1991 to 1993, real estate prices fell from exorbitant levels to merely immoderate levels. At the same time, the stock market fell nearly 60%. These two falls wiped out immense amounts of paper assets and, with the recession of 1992 and early 1993, raised questions about the possibility of an economic ‘melt down’, a downward spiraling recession as people reacted by not spending, forcing losses on even the largest companies for the first time in decades. The stock market has strengthened and to a certain extent recovered, suggesting that the worst fears were never more than that, but the experience has underlined a long-standing feeling among many Japanese that their economy is a fragile one.

Added to these difficulties is the steadily rising value of the yen which stayed at 360 to the US dollar for decades, but rose to less than 110 to the dollar in the middle of 1993 with expectations of further strengthening. Each increase in the yen’s value has put pressure on the profits of export industries. At some point, Japanese exports could be priced out of foreign markets, casting further doubt on the economic health of the nation.