Trains came to Japan late and like many technological advances railways arrived after being well developed elsewhere. This allowed the Japanese to begin building in the 1870s with a good view of the technological choices they needed to make. Early railroads were constructed by the government which decided on a standard gauge; henceforth, the government’s rail system has avoided the pitfall of many other systems which found local authorities or private companies had opted for a variety of rail widths.

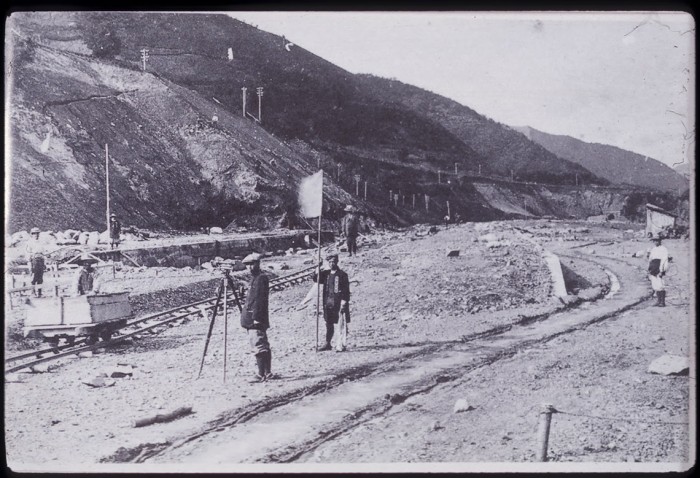

The first railroad was a short link between Tokyo and Yokohama, completed in 1872. A second system connected Kobe and Osaka in 1874, with extensions to Kyoto in 1876 and Otsu on the Nakasendo in 1880. Plans were made in 1883 to link Tokyo and Kyoto along the Nakasendo. This inland route would provide protection against attack by foreigners from the sea. Some portions were gradually completed. In 1886, however, plans for the main trunk railroad were switched to parallel the Tokaido highway from Tokyo to Nagoya and the Nakasendo after Sekigahara. This route followed terrain that was easier for construction crews. Fewer tunnels had to be built and the steep Kiso River gorges were avoided. The change also took the trunk line through the major population centers of Tokyo, Nagoya, Kyoto and on to Osaka and Kobe. The change improved communications where most needed and ensured the financial success of the undertaking.

Although the Nakasendo was abandoned as the main Tokyo-Osaka trunk line, a major line along this route was finally completed. Today, it is possible to parallel the old highway by train, but many of the old post-towns were too inaccessible to the route of the train. The effect of this was immediately apparent when the train line was finally completed in 1911. Post-towns which received stations continued to see passenger and freight traffic flow through; they maintained a level of prosperity that kept people living in the town. Post-towns which were by-passed noticed a sudden change. Nobody except local residents appeared on the main street which formerly, even in the Meiji period, saw many days when one or two thousand people might pass through. Prosperity disappeared and the population dropped as young people, and sometimes entire families, moved away.

Families who had the capital and skills to take up other occupations were the ones to survive the stress of this kind of change on the Nakasendo. Often, inn owners had been involved to a small extent in other businesses: freight handling, food processing, sake making, and money lending were common. Some families moved quickly into money lending, then “sake” making, then farming in order to keep pace with the changes that occurred from the 1920s on. In the past twenty years, tourism on a low level has returned to some of these smaller, by-passed post-towns, such as Hosokute, and some of the families have returned to the inn business as tourists begin to search out hard-to-get-to places. In these towns, however, the level of tourism is so low that the reopened inns are really only in demand during the summer school holidays: the rest of the year they are open, but very few travelers venture beyond the former post-towns with train stations.

Former post-towns with train stations, such as Gifu, Nakatsugawa, or Karuizawa, have had different experiences. The train system brought the possibility of growth in the mainstream of national development. Nakatsugawa has grown into a city of 53,000 with several large industries while Karuizawa is now a major tourist and resort area complete with tennis courts, golf courses and exotic, European-style buildings. Still other post-towns such as Omiya, or Urawa, and Kumagaya near Tokyo, and some intervening rest-stops, have grown into large cities, serving as major transfer points on the transportation system for metropolitan Tokyo’s commuters. In these towns, the train station is now the center of town and business and local roads radiate away from it. The old post-town structure can still be found buried beneath the new structure, but it may require an expert eye to distinguish the old route.