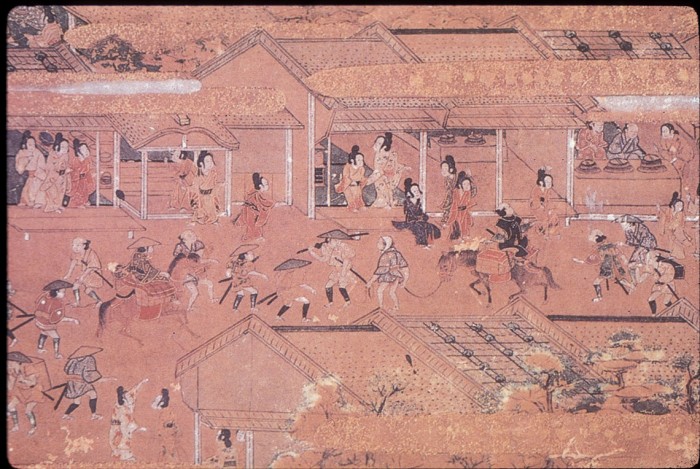

Post-towns were spaced out along the old highways of Japan for the convenience of travelers. In the eyes of the Tokugawa government, ‘travelers’ were officials, daimyo and samurai who were moving around on business connected either with their administrative responsibilities or with the system of alternate attendance (sankin kotai). The term did not include individuals who were traveling for pleasure or on pilgrimage, merchants moving themselves or goods from place to place, others who were involved in commerce, or commoners moving in search of employment.

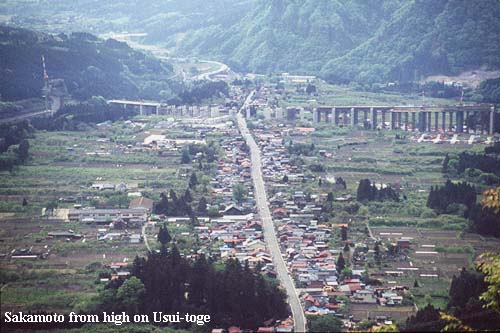

In short, the post-towns and their services were strictly official in the eyes of the government. Of course, during the course of the Edo period, commercial activity increased far beyond any level desired by the government at the beginning of the period and the nature of traffic on the roads changed significantly. This in turn forced a great deal of change on the post-towns and the way they functioned.

Post-towns were the centers of the government’s control over the use of the highway system. Post-towns also supplied the needs of travelers and provided policing of the highway. Government control included insuring that official travelers were tended to according to their importance or the importance of their business. Travelers, whether samurai, daimyo, members of the Tokugawa house or government, or members of the Imperial court, were all ranked according to their position in society.

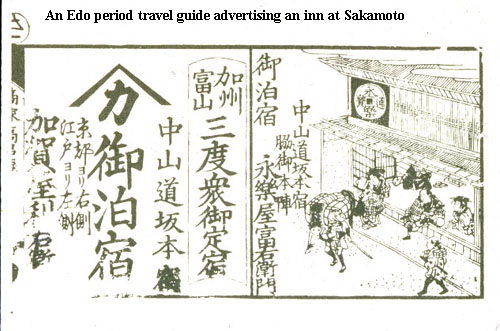

The post-towns provided services (food, drink, accommodation and transport) in accordance with rank. Thus, the highest ranking daimyo stayed in the primary inn, the honjin, and a second-level daimyo was put into the second best inn, the waki-honjin. Since there was usually only one of each in a town, care in travel schedules had to be maintained so that conflicting claims for the top inns did not occur. Lower classes of travelers were relegated to correspondingly lower quality inns.

The post-town was also a means of policing the road, although to a lesser extent than the barriers or seki. Crimes committed by travelers were to be reported to the authorities, of course, but reports on suspicious travelers were expected of townspeople. Women who might be trying to escape being hostages in Edo under the system of alternate residence, samurai trying to sneak into Edo, and weapon smugglers were to be watched for and arrested.

Most important, perhaps, were the services which the post-towns provided to travelers. In return for cash payment, the post-towns provided accommodation, food and drink to travelers. They also provided porters, beasts of burden, changes of horses for fast messengers and all the other services and items which travelers required. Preference was accorded to officials, daimyo and samurai.

The post-towns and highway system, however, soon came to service a large number of commoners who began to travel more and more in response to the growth of commerce and trade in the Edo period. These travelers increased the economic activity of the post-towns and also placed a strain on them. As demand for services increased, if the town did not grow, services could only be diverted away from the official travelers. Merchants had sufficient cash to attract the services which they required and were often able to obtain the same services enjoyed by the the samurai class when traveling, thereby confusing the Confucian social structure which put the merchants at the very bottom of society.