During the 7th century a centralized political state gradually emerged, providing the foundations for a unified Japan under the direct control of the emperor. After a number of imperial palaces had been built, then later dismantled, at various sites near modern-day Nara and Osaka the first imperial and administrative capital was built at Fujiwara at the end of the century. In 702, national administration was strengthened by legislation known as the Taiho Code. Under this Code, a system to impose imperial control at local levels throughout Japan was formalized, including mechanisms for tax collection.

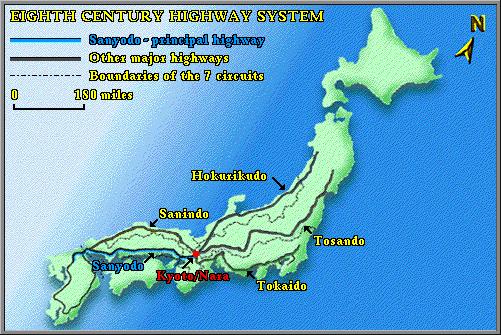

8th Century Highway System

The country was divided initially into 58 provinces (kuni), each with a provincial capital (kokufu), modeled on the layout of the national capital at Fujiwara. The provinces were further grouped into larger territories, or circuits, totaling eight in number. Each circuit was then linked to the capital at Fujiwara by a highway. One of these highways – the Tosando – later became the Nakasendo. The original construction of the Nakasendo highway is therefore usually dated at 702.

Each provincial capital was under the control of an administrator who was responsible for the maintenance of law and order, the recruitment of conscript labor for public works and military service, and the collection of taxes. Following the pattern of the capital at Fujiwara (which was in turn modeled on the capital cities of China at this time), the provincial capitals were laid out with a grid street pattern, the principle alignment being in a north-south direction. The offices of the administrator were usually located in the northern central part of the city, emulating the location of the imperial palace in Fujiwara.

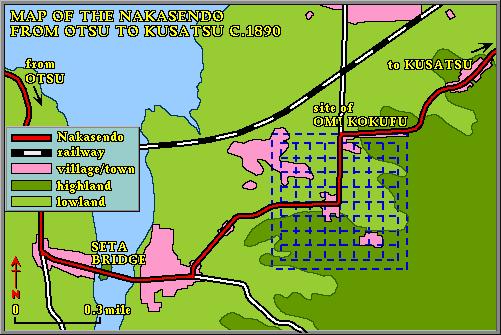

At Omi Kokufu, however, the layout was somewhat different. Omi Kokufu occupied an extremely important strategic site, protecting the crossing point of the Seta River and the eastern approach to Fujiwara. The land here has a gentle downward slope from south to north, and it would be unseemly for the government offices to be located on low-lying land at the north. The offices were therefore located in the southern central section of the city.

Within just a few years of the founding of this urban network the imperial authorities realized their capital at Fujiwara was too small to administer the system efficiently. It seems there was simply not enough room for all the administrators and their offices. In 710, the capital was moved to a much larger site at Heijo-kyo, known today as Nara. Much the same layout was used, with a north-south alignment within which streets were laid out in a grid pattern. The major differences with Fujiwara were that the palace at Nara was moved so that it was now adjacent to the north wall, and an extension ‘arm’ was built on the eastern edge of the city. This extension was the only part of Nara which survived into later centuries.

Todaiji

Although intended as a permanent capital, political rifts between the court and religious monasteries in the city caused the court to move once more, in 784, and to leave the monasteries behind in a ‘dead’ capital. The most notable example was Todaiji, which had been built originally to emphasize the supreme power of the emperor. Even today Todaiji is the biggest tourist attraction in Nara, but its ability to draw pilgrims throughout the centuries is possibly the main reason why Nara managed to survive at all.

Construction of a new capital city was begun at Nagaoka, a little to the south-west of modern Kyoto. A series of natural disasters and political mishaps, however, led the court to believe that the omens were wrong for this site. Ten years after the move from Nara, in 794, another move was made to the site which would finally become the permanent imperial capital for a period lasting more than one thousand years. This was to be Heian-kyo, later renamed Kyoto. Despite destruction from time to time by fire, earthquake, war, and pestilence Kyoto has survived and is now the fifth largest city in Japan. Few of the provincial capitals (kokufu) founded in the eighth century managed to survive the political turmoil of the next few centuries, however, and , as imperial power waned, so did they fade into almost complete obscurity. It was not until the period of castle towns construction in the early seventeenth century that Japan again witnessed such an intense period of urban growth.

Provincial capitals