Most accounts date the origins of a national system of highways to 702AD: the year of the Taiho Code. Among other things, the Taiho reforms formalized a system of national administration (known as the “Ritsuryo system”), based on a division of the country into seven major regions, or ‘circuits’, and an additional one incorporating the five ‘home provinces’ (Kinai) immediately surrounding the capital itself. Below this level, the country was further divided into 58 provinces (kuni), each administered from a provincial capital (kokufu) where rice tax was gathered before shipment to the imperial capital. In order to facilitate the movement of these tax payments, and to allow the rapid movement of imperial troops around the country or, in times of peace, to provide for good communications generally, each circuit was linked to the capital by a highway.

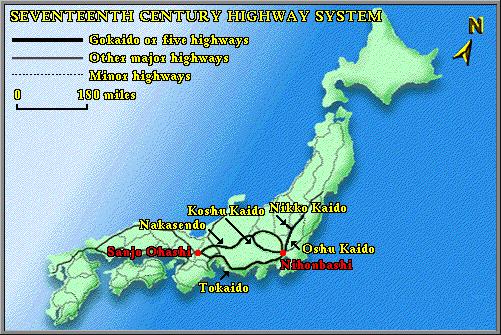

A small degree of confusion arises because the circuits and associated highways shared the same names. To the east of the capital, for example, the circuit along the Pacific sea-board was called the Tokaido. The region is still referred to commonly by this name today. The Tokaido is also the name of the highway which ran through the region, being more or less the same road which gained prominence around one thousand years later in the Edo period. Much of the route of the Nakasendo was also pioneered under the Ritsuryo system, except at that time the highway was called the Tosando. This was also the name of the largest of the circuits, stretching the length of the central mountain ranges and extending over almost all of modern day Tohoku, the northern island of Hokkaido and the northern segment of Tohoku were not then under imperial control). Also in the east, along the Japan Sea coast, was a third circuit/highway known as the Hokurikudo. To the west of the imperial capital the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu formed the Nankaido and Saikaido circuits respectively, and south-west Honshu was divided into the San’indo (Japan sea coast) and San’yodo (Pacific coast) circuits.

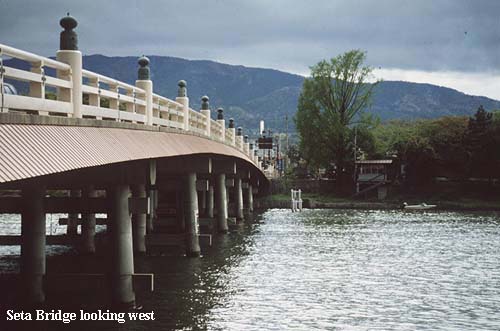

There is some controversy today concerning when the Ritsuryo system was first conceived, and when it was brought into effect. The “Nihon Shoki” (written in 720), for example, claims the system originated in the Taika Reforms of 646, although modern scholarship has shown clearly that many of the historical claims of this chronicle are, to say the least, of dubious value. Nevertheless, there is other historical evidence to suggest that many of the features of the Tosando (Nakasendo) highway were in existence before 702. The battle at Seta Bridge, for instance, took place during the Jinshin rebellion of 672 and, largely in consequence to this event, the barrier station at Fuwa (Sekigahara) was erected the following year. Surely there would be little point placing such a station if there were no road to guard?

Whatever the precise origins of these roads, and their early status, there is no doubt that by the early 8th century they had been declared ‘official’ highways. As such, the seven highways were ranked into three grades: the dairo, or principal highway (San’yodo), two churo, or secondary highways (Tokaido and Tosando), and four shoro, or lesser highways. The San’yodo was awarded prominence because it connected the Kinai with Daizaifu, an important provincial capital in northern Kyushu]. Possibly this is suggestive of the idea that this region was the original homeland of the ruling Yamato clan, but more likely is the explanation that Daizaifu was the point of arrival in Japan for Chinese and Korean emissaries and skilled craftsmen. Even today, many Japanese like to think of this highway as the final leg (or first stretch) of the ancient Silk Road. Whatever the case, the status of the highway was such that the post-stations along it were obliged to keep 20 horses available at all times for use by official travelers, compared to only 10 horses required at post-stations on the secondary roads and 5 horses at stations on the lesser roads.

Like many other features associated with government at this time, Chinese influence was very strong. The highway system was, at first, a direct copy of the road system in China established during the Chou dynasty (1122 – 222BC), and subsequently improved in the Chin dynasty (222 – 207BC). Contemporary descriptions of the Chin highways suggest they were 50 paces wide and lined with ‘shade trees’ (in Japanese, namiki), each at an interval of every 30 feet. The roads were paved, or well compacted, and served by post-stations at intervals of every 30 ri (approximately every 70 miles). Fresh horses could be obtained at the post-towns, but only by those on official business. The Taiho Code stipulated similar dimensions for the Japanese highway system, but the practicalities of traveling in a much smaller country than China, over consistently rugged terrain, meant certain adaptations to the Chinese system had to be made. In reality, therefore, Japanese roads were probably somewhat narrower than their Chinese counterparts, and post-stations were placed at an average interval of only 5 ri (12 miles).

Torii-toge

Travel by common folk, though not prevented was hardly encouraged. Barrier stations were set up on the highways to check against any ‘undesirable’ movement of people and goods, and virtually no services, such as provision of food and lodging, were available. Moreover, in remote areas where imperial control was weak, travelers were subject to the attention of highwaymen, bandits and muggers – call them what you will, traveling was by no means safe. As imperial control waned further, especially during the Heian period, and control over the roads fell to avaricious local interests, so travel became even more difficult. The system never broke down entirely, however, and when Tokugawa Ieyasu issued edicts in 1602 for the re-establishment of a national highway system many of the features of the original Chinese model were retained. Even the routes followed by many of the Edo period highways were essentially the same as those laid down some 900 years earlier.

17th century Highway System