Although only a small town, Ashita boasts the oldest surviving honjin on the Nakasendo. It has also been owned by the same family since its’ original construction in the late 16th century. Ashita honjin offers a unique opportunity to observe one story of the changing fortunes of the most important building in any post-town, from the time the Nakasendo was first conceived to the present day.

The Ashita honjin stands at an intersection in the center of the town. Diagonally across the street is the site of the former waki-honjin which has been replaced by a modern building selling seed and fertilizer. Opposite is a sake brewer and warehouse. In October 1992 the corner of the honjin was being converted into a shop, but just beyond that is the gate through which Princess Kazunomiya, as well as many daimyo, passed in the Edo period. Today’s traveler is welcome to enter and, if the time is right, Mr. or Mrs. Tsuchiya may be free for a guided tour and a chat.

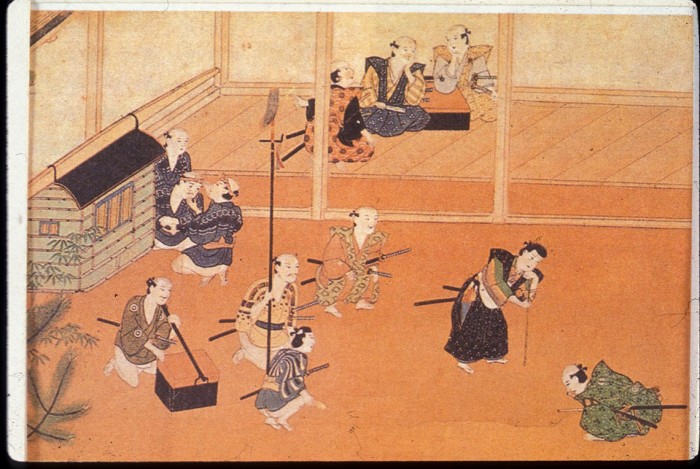

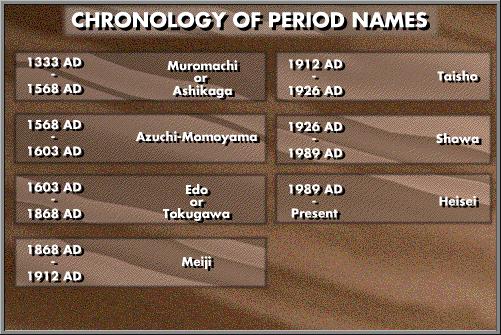

The Tsuchiya family history stretches far back in time. The family were important retainers of Takeda Shingen when he was the sengoku daimyo of the area. A painting commemorating the Takeda clan shows a Tsuchiya in a prominent position. Shingen was a failure, however, eventually losing to Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, so in the end the Tsuchiya family withdrew from the samurai class to become large landholders at Ashita. When the Tokugawa shogunate set up the administration of the Nakasendo highway, bygones were forgotten and the Tsuchiya, being the most important family in the town, were ordered to establish and maintain the honjin. The family had already established an inn which was being called the honjin in 1597. The present building where Kazunomiya spent the night in 1861 had been rebuilt after a fire in 1800, but its origins as an inn can be traced back four centuries now.

Many honjin no longer exist. They were large, too large to maintain in the changed circumstances after the Meiji Restoration. It is ironic that the Ashita honjin survived, for Ashita was one of the smallest post-towns at the end of the Edo period with a population of only 300. The Tsuchiya were able to maintain the honjin largely intact until 1945 because they still had large amounts of rice land and forest land which they rented out. After 1945, most of their land was taken away in the land reform of the Allied Occupation which stripped land from non-farming landlords and sold it to the tenant-cultivators at low prices. Good for the farmers, for sure, but it made life very difficult for the Tsuchiya to continue to maintain the honjin. As a result, the present head of the family has found it necessary to take up alternative employment. He is now a high school teacher and his wife too was at one time a teacher. School teachers, in a country that values education highly, hold important positions in the local community, not unlike the prestige of a honjin master.

The honjin is open to the public although a part of it remains reserved for use by the family as a library. Visitors are welcome to walk the length of the building, viewing the name boards of some of the daimyo who visited regularly. Originally the name boards would have been placed in front of the honjin whenever the daimyo was in residence. Back in the private quarters where Kazunomiya stayed, her visit is commemorated with small metal chrysanthemums (the Imperial insignia) nailed to the wood-work. Further back is the toilet which, mimicking the style of daimyo residences, has a small drawer in which is a piece of paper and some sand. These were removed, emptied, and cleaned after each use. Spies often would pay large sums for information about a daimyo’s health, so it was important to secretly dispose of his refuse.

Without their lands, the Tsuchiya struggled on their teachers’ salaries to keep the honjin in good repair, but old buildings have become extraordinarily expensive to maintain properly. Recently, the prefecture took on the cost of maintenance, but the Tsuchiya now have to secure approval for every change or repair on this part of their home. Twenty years ago, they built a modern house which, with heating and air-conditioning, is far more comfortable than the honjin ever was.