Just before noon on the first of September, 1923, a huge earthquake struck Tokyo and the surrounding Kanto region. Registering 7.8 on the scale used by the Meteorological Agency of Japan, the initial tremor was followed by hundreds of small and one more large earthquake during the following days. They added to the worry and panic of residents in the region, as if they did not have enough to worry about.

Japan has always been prone to earthquakes sitting as it does on the edge of one continental plate which has another one dip under it. Each year sees numerous small quakes and every so often a larger one. The really destructive ones come only occasionally, but far too frequently for comfort.

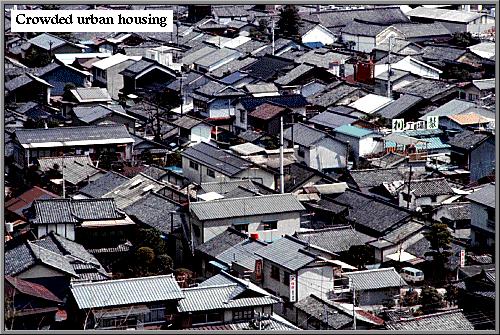

The 1923 earthquake was one of the most destructive ones. As was usual in the past, the earth’s movement itself did some damage: a few homes were knocked down, some large splits in the earth were found, some roads and railroads were displaced several yards, and the Great Buddha statue at Kamakura was dislodged from its foundations. Far worse, though, was the damage caused by fire. Natural gas lines spouted fire and cooking fires spilled their coals across wooden kitchen areas. Within minutes, hundreds of fires sprung up across wide areas in the old, crowded centers of Tokyo and Yokohama.

The earth’s movement cut most of the water mains, so where firemen were able to respond to alarms, their hoses had nothing to carry. Quickly the fires spread and joined, creating a virtual firestorm that consumed all oxygen and flammable materials. Where the fire was concentrated, nothing could survive the heat and lack of oxygen. The quickly rising superheated air gave rise to cyclones which are otherwise rare in Japan.

The statistics on damage are impressive. Out of a population of some 11,758,000 in the region, 3,248,205 lost their homes, 104,600 were killed, and 52,000 were injured. In Tokyo, nearly 71% lost their homes, mainly to fire, and in Yokohama, almost 86%. Property damage was estimated at up to 10 billion yen (about US$5 billion) and the official figure was over 5 billion yen.

Damage was far more severe in built-up urban areas where the wooden houses offered few barriers to the flames. Public parks and open areas were then as now small in size and number, so they formed poor barriers and offered little protection from the fire. The Honjo Military Clothing Depot sheltered nearly 40,000 people until a cyclone, filled with superheated air, passed over, killing them all. But a few thousand yards away, people who clustered in the grounds of the Nikolai Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Kanda survived, as did the church. In rural areas, fires were fewer and did not spread, so only a small proportion of buildings were destroyed and few people were killed: only 12,600 died in rural areas.

Rebuilding the Kanto area was a major undertaking by government and individuals alike, even with emergency aid which came from all over the world. Rebuilding was accomplished with such speed that the same narrow streets which Tokugawa Ieyasu laid out with their dog-legs and circular meandering were reproduced, the crowded lots were replicated, and the same flammable woods were used. The city remained vulnerable to another damaging earthquake, but it was Allied bombs which next put the city to the torch.