Like all major urban areas in the world, Japanese cities have seen massive suburban expansion in recent decades. The nature of suburban development, however, has been significantly different from that in most other countries.

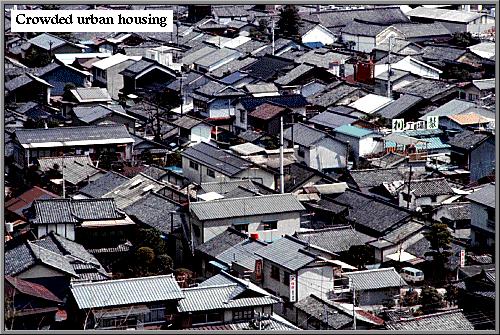

shortage of habitable living space

Many Japanese suburbs have developed around what were once small villages and towns rather than as divisions or subdivisions carved out of unpopulated farmland. This gives suburbs the feeling that they are simply overgrown villages which are connected by railroads to each other, but which nevertheless maintain a distinct and autonomous identity. Clustered around each suburban train station are numerous small shops where commuters and housewives shop on a daily basis. Travel to the stations is generally by foot or bicycle as the suburbs are usually compact, small, and densely populated.

In larger metropolitan areas, the pattern of suburban growth is termed the ‘donut effect’. This refers to the fact that the areas of fastest population growth occur in an ever expanding ‘ring’ around the city core. In Tokyo, for example, this ring now centers on a radius of some thirty miles from the downtown central business district. The city centers, meanwhile, are becoming increasingly depopulated as commercial developments take over former residential areas.

One of the unusual features of this pattern of development is the existence of zoning laws which permit farmers to retain agricultural land in the suburbs. As long as the land is farmed, it is taxed at a lower rate than that for urban development. As a result, many farmers hold on to land, waiting until the price inflates due to increasing urbanization. The result is that even densely populated ‘new’ suburbs are broken up by cabbage or vegetable patches. Rice farming becomes impossible after a certain degree of urbanization is reached because the irrigation system becomes too disrupted to support a single field.

The dominance of small shops in suburbs is also peculiar in comparison to some countries. The law in Japan protects small, family-owned shops to a great extent. Usually, large supermarkets or department stores are banned from building close to suburban train stations or may only be built after agreement by the owners of small shops in the area. This agreement is seldom forthcoming because the chain stores can usually sell at lower prices and thus threaten the continued existence of smaller enterprises.

Another interesting aspect of suburban development in Japan is that there is seldom deterioration of a suburb over time with house prices falling as the homes become older and poorer people move in to take advantage of the lower prices. One reason for this is a better distribution of income than might be expected; most people feel quite rightly that they are middle class. Another reason is that land values stay so high most of the time that families who need more space or newer, more comfortable homes tend to knock down and rebuild their homes on the same piece of property rather than move to a ‘better’ neighborhood. With the prosperity of recent years and the rapid deterioration of cheap houses built in the aftermath of World War II, many families in Tokyo have rebuilt using either custom designed plans or well-planned prefabricated homes which are available for viewing as model homes on sales lots throughout the city.

Life in a suburb can be difficult. Japanese social groups are not particularly inclusive; they do not welcome new members in most cases. In existing villages which grow into suburbs, the older residents usually form a group which excludes the newer residents from social groups and power-holding. In-coming residents are not only isolated from existing social organizations, but they find it difficult to find an excuse to form organizations with other newcomers. Families can find that they are socially isolated except from the husband’s place of work.

Alternatively, a company may move into a suburb and build apartments or homes for its workers. Within such a development there will necessarily be a social organization, often based on the husbands’ power within the company. In any case, the development will be socially independent of the rest of the neighborhood. Residents may not be socially isolated, but they have no more relation with the suburb than the isolated newcomers described in the previous paragraph. Yet again, in large apartment building complexes, it is very difficult to build up social relationships. Newcomers arrive with no human relationship to their neighbors and find it very difficult to break down the barriers. It is done, of course, but with a great deal more difficulty than in many countries.