The climate of Japan is influenced by its position on the eastern edge of the Eurasian land mass (thus Japan is subject to the effects of both continental and maritime winds), by its latitudinal position (in the temperate zone), and by the annual movement, north and south, of a series of fronts separating different air masses. The dominance of a particular air mass for part of the year gives rise to monsoon conditions which characterize, in particular, the winter and summer seasons.

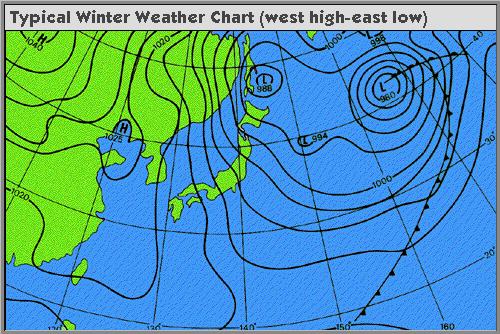

This ‘west high – east low’ weather pattern

In winter, which lasts from mid-December until the end of February, the Polar front lies to the south of Japan and so the country is exposed to the influence of the Siberian continental air mass. The winter monsoon is characterized by a steady stream of cold northerly winds, which increase in intensity if an area of low pressure is situated over the Aleutian islands to the north east of Japan. This ‘west high – east low’ weather pattern invariably brings great quantities of snow to the Japan Sea coastal regions, moisture having been picked up by the monsoon winds during their passage over this stretch of water.

The retreat of the Polar front northward in early spring brings a period of fine, settled weather from March to the end of May. Broken only by occasional frontal storms, the climate at this time of year is generally characterized by an eastward moving ‘migratory high’ weather pattern. The advent of spring is marked by a wave of pink moving south to north when the cherry blossoms make their brief appearance as the country warms.

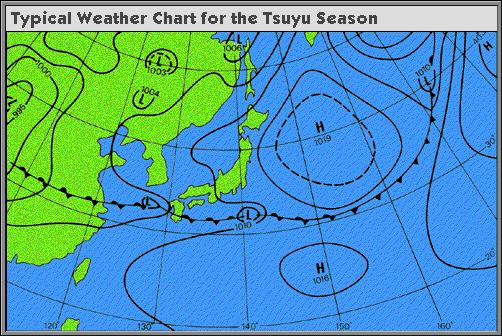

In June the Polar front (south) pauses during its northerly retreat to rest stationary for a while over southern Japan. Warm, moist air from the Ogasawara high pressure system meets cooler, northerly winds along this front, giving rise to a protracted period of rain and drizzle. This is known as the tsuyu’, or the ‘plum rain’ season. Hokkaido, located well to the north of where the front is usually situated, does not experience much rainfall during this season but in Kyushu torrential downpours may occur if there is a surge of the equatorial monsoon from the south west. The result may be flooding and landslides causing loss of life.

In June the Polar front (south) pauses during its northerly retreat to rest stationary for a while over southern Japan

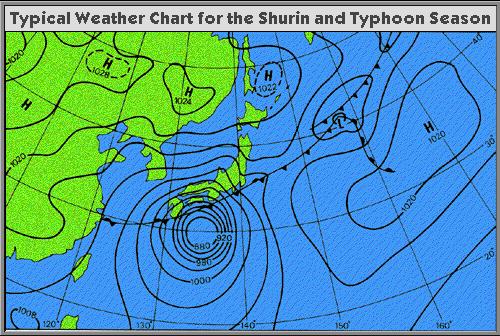

During summer, in July and August, the Ogasawara high dominates and the weather becomes hot and humid as a southern maritime airstream prevails. Then, as the Polar front (south) moves south in September a second rainy season (the shurin season) occurs. Generally the rains are of less intensity than in the tsuyu season, although the weather pattern is essentially the same. Heavy rainfall and strong winds do occur at this time of year, however, with the passage of typhoons originating in the sub-tropics east of the Philippines. Finally, as the Polar front continues to move south from October to mid-December the ‘migratory high’ weather pattern reappears, bringing fine and settled late-autumn weather.

The passage of typhoons

This cycle of seasonal change, whilst consistent from year to year, does not result in a uniform climate across all Japan. Instead, marked regional differences are evident, which contribute to the pattern of contrasting landscapes we see in Japan today. First, moving south to north across the country average temperature falls and precipitation becomes less. This change has a strong influence on the type of crops which can be grown in different parts of the country. Second, the amount of precipitation along the Pacific coastal areas peaks during the rainy seasons of late spring and early autumn. In contrast, the Japan Sea coastal areas record greatest precipitation during winter when it falls as heavy snow. The depth of this snow is usually so great that whole communities may be cut off for days, weeks, or even months at a time. Without doubt this fact has contributed to the relative lack of industrial development in this region, and to the severe depopulation suffered in many villages here in recent decades.

Extreme weather conditions, including heavy snow, torrential rain during the tsuyu season, and the passage of typhoons may cause loss to life and property. The need to reduce the risk of flooding has led to the construction of high levees along river banks in the alluvial plains, while in areas of heavy snowfall houses are built with steep gabled roofs to reduce the risk of collapse and streets have covered walkways to allow free passage when roads are blocked by snow.