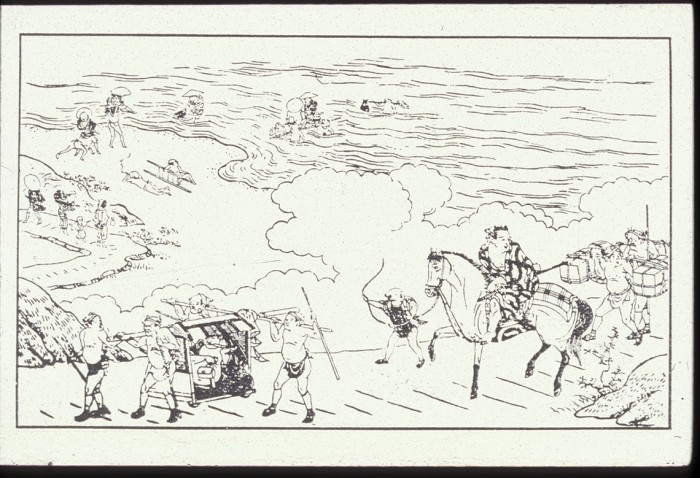

The Nakasendo was considered an easier route than the Tokaido because it had fewer crossings over large rivers. Rivers in Japan are serious barriers to land transport because they are wide, not navigable and prone to sudden flash floods. Many a travelers’ tale, then, turns on mishaps at river crossings.

In the Warring States period, daimyo discouraged bridge building because of the advantage they might have given to advancing enemy troops. In the Edo period, however, the Tokugawa shogunate wanted a speedy and efficient transportation system and they therefore encouraged the building of bridges. Not every river was bridged, however, possibly because a sudden flood would wash away these expensive investments so easily.

Therefore, travelers had to either negotiate the crossing themselves or rely on help from local people. Since the locals had better knowledge of the idiosyncrasies of their particular crossing, the later course was often employed. Most crossings which were substantial had a regular group of men who offered their services to travelers for cash. The prices were fixed, like porterage fees, which were posted on kosatsuba (or official proclamation boards) at post-towns. The porters often took advantage of bad weather, however, to negotiate a higher fee.

kosatsuba

The crossing was sometimes accomplished by two or four men loading the traveler onto a wide plank and carrying him across, but a cheaper and more common way was for the porter to lift the traveler on his back and wade through the water. If there was a deep patch, or if the porter lost his footing, the traveler would get wet anyway.

The first bridge at Tarui was built for one of the Korean embassies which made the trip to Edo in the first half of the Edo period. There is still a sign which duplicates the prices for the river crossing before the bridge: so much if the water came up to the knees, and more if it was up to the chest.