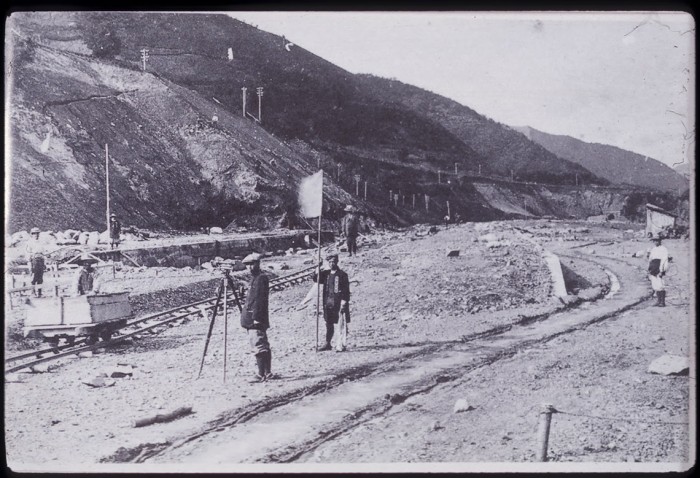

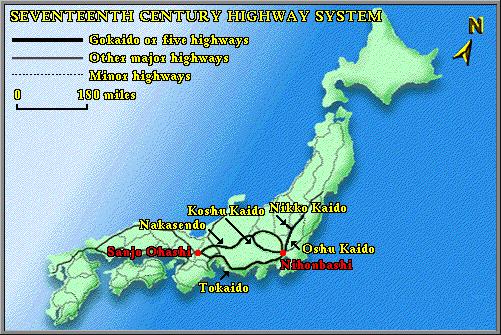

The Japanese government correctly perceived at an early date that a good railway system would be beneficial to the economy. The first small railway ran from Tokyo to Yokohama in 1872, but gradually the system was extended until it connected Nagoya, Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe, the main cities of the center of Japan. Soon freight and passenger services were in great demand. Commerce in the Edo period had been hampered by the extreme difficulty of moving bulk goods overland; even movement by travelers was not easy although the well-administered highways like the Nakasendo helped speed travelers along. Most heavy goods had to move by sea and internal water connections were not good because most rivers were short and shallow. Railways promised not only to link the main cities by land, but to open up the land between to trade and commerce as they had never been before. The first Tokyo to Kyoto trunk line was completed in 1889 and followed the coastal highway, the Tokaido, as far as Nagoya, then it turned north to follow the Nakasendo from Sekigahara, although original plans had it running along the Nakasendo through the mountains.

17th century Highway System

Private railways were also established, but in 1907 many routes were nationalized and the private companies were left mainly with commuter lines around the large cities. Private railways in Japan have grown into some of the largest companies by branching into other businesses. Land purchases next to stations were developed into housing areas or resorts, shopping centers or department stores. These developments drew passengers to use the trains which then became profitable.

The national railways have both profitable and unprofitable operations. Restricted mainly to railroading and excluded from profitable side-lines like department stores, the national system was also used by the military for its uneconomic purposes before 1945 and by politicians as a source of public building projects which stabbed numerous small lines deep into politically important rural areas, yet never turned a profit. The main trunk lines, commuter lines in the large cities and the Shinkansen turn handsome profits. In the 1980s, privatization of the national system began and many steps were taken to improve profits and service while maintaining many of the loss-making local lines.

The many private and public lines are complementary, rather than competitive with each other. In Tokyo, for instance, recent expansion of the commuter network has seen connections develop allowing trains to run from the public system through the tubes of the subway system and out the other side of the city on private rails.

The Shinkansen was developed in the 1960s together with other public works in conjunction with the 1964 Tokyo Olympics as a showcase of Japanese development and technology. These high-speed trains now run from the southern island of Kyushu to the northern island of Hokkaido. Carrying only passengers in densely populated Japan, the Shinkansen lines are marvels of technology, profitable, and as fast as air travel from city center to city center. Good not only for interurban travel, they have become favorites of commuters who are now able to live in former rural areas far from the high land prices of the cities. Plans to extend the Shinkansen system will bring it throughout the Japanese islands. Being quick, safe and comfortable, the system dominates passenger transport where it runs: in the early 1980s, the Shinkansen carried nearly 95% of the traffic between Osaka and Tokyo. The social cost of putting the system in, however, has caused some difficulties. A line planned from Tokyo to its international airport at Narita has been abandoned and the link between the line north of Tokyo and west to Osaka has never been finished due to opposition from residents.

Trains and stations are monuments to history. Tokyo station, for example, has as its oldest part a nearly Victorian, red brick structure which is lovely and totally out of date (although modified enough to service modern requirements). It has within it a plaque which labels the place where Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi was shot in November 1930. Tokyo station is also a statement about the growth of transportation needs. It has subway lines which come in underground; it has commuter and long distance lines which arrive and depart even deeper underground; the train lines above ground have been elevated to allow space for vestibules and pedestrian ways; and the newest Shinkansen rails are raised even higher. Since millions of people traverse the station daily, there is a complex of shops, hotels, department stores, and, fortunately, information booths. Some are deep underground, a few are at ground level, and there is a station building which rises high above the old, Victorian building.

Out in the country, along the Nakasendo, traffic in stations has dropped off to a low level as people have left rural areas for the cities. As employees reach retirement age, many stations no longer justify manning: they have only a machine which issues a coupon stating the passenger’s place of origin and the fare is settled later. Yet these stations too may be historical; they may have a roof supported by old rails which are stamped with the sign of the Imperial Russian railway system and a date of 1901 or 1902. These were often ripped up following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5 as war booty or during the Siberian Intervention at the end of World War I and probably served time under passenger and freight trains in Japan before being retired to hold up the roof.