Porters and carriers were the primary means by which goods, travelers and their baggage moved along Japanese highways. When the first ‘official’ highways were established in Japan, probably in the 7th century AD, one of their most important functions was to facilitate the smooth passage of the rice tax due to the emperor each year. Poor maintenance of these roads, and the lack of suitable rest-stops, meant that the carriers of the rice tax, or tribute, could often spend more than a year on their arduous, and dangerous, round-trip journeys. This inefficiency meant that, at best, the court could not rely on getting its revenue on time, and that, at worst, some local administrators would not bother to send the rice tax at all.

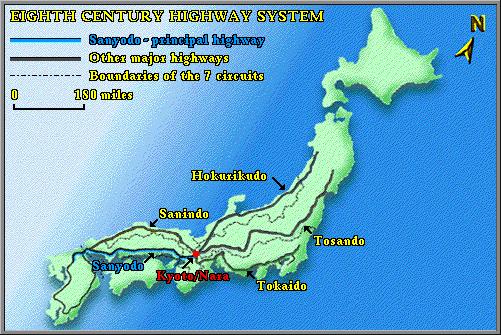

8th Century Highway System

Imperial reforms in 702AD attempted to improve this situation by setting up a more comprehensive system of suitably managed post-stations. These offered, among other things, food, lodging, and temporary security to official travelers. Other travelers such as merchants, however, had to continue to make do without these facilities. The post-stations’ services were not available to them and unofficial inns and other business developed in the post-towns to serve their needs. As far as the ‘tax carriers’ were concerned, it appears that they were still expected to complete the full round-trip journey, even from the farthest reaches of the empire. The only concession to them was that a stock of drugs and medical essentials be made available at post-stations, to help ensure they did not expire on the way.

By the time that Tokugawa Ieyasu had seized the shogunate, and established a new set of regulations for administration of highways in 1602, the function and status of porters

and carriers had clearly changed. The Tokugawa authorities ruled that a quota of porters and pack-horses be maintained at every post-town. Their function now was to carry people and goods in transit from one post-town to the next one, and no further. On completion of their work, porters would normally return to their homes on the same day, preferably with a load to carry back on their return journey. If nightfall approached there was always the risk of having to spend a night at the adjoining post-town, perhaps offering the chance for a night-out with neighboring workmates at a cheap inn or tea-house. Traveler’s accounts of life in the post-towns seem full of stories of the rowdy and boisterous nature of the porters. Some accounts, however, suggest that porters wishing to get home as the sun went down would willingly swap their loads with other porters, in similar situation, going the other way.

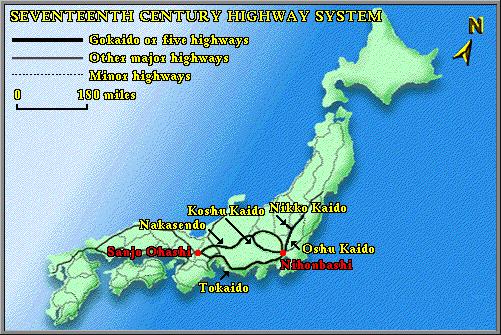

17th century Highway System

Transport agent house

The quota of porters and pack-horses for each post-town was fixed according to the status of the highway. On the Tokaido, the busiest of the highways in the Edo period, the usual quota was one hundred of each for every post-town. On the Nakasendo the quota was reduced to fifty of each in most instances, and to twenty-five porters and twenty-five pack-horses for those post-towns in more mountainous districts, such as the Kiso valley. Rates of conveyance were fixed according to the distance between post-towns, as measured by the number of ichirizuka (mile-posts), and by the severity of local terrain. Management of the porterage system was the responsibility of the appointed tonya (transport agent) in each post-town. Porters could have their services hired to any traveler, but their main function was to be available for transporting high-ranking officials and their (often voluminous) baggage.

On occasion, the procession accompanying very important people required that more than the allocated number of porters and carriers should be available. The journey of Princess Kazunomiya to marry the shogun in 1861, for example, required as many as 8000 porters and 3000 horses to be available on the day she arrived at each post-town she stayed at. To cope with this kind of situation, the tonya were authorized to recruit extra labor from designated surrounding villages, known as sukego. Often this might interfere with the villagers farming routines and so, it was argued, they would not be able to harvest sufficient rice to pay taxes. The system led to much discontent, therefore, and even to rioting from time to time.

In the Meiji period the strict regulations imposed on these road services disappeared. The rickshaw was now a common sight, having displaced the kago or palanquin for carrying passengers on smoother sections of the road. The carriers were also free to impose their own rates of hire. As one early European traveler observed:

“An argument with a Japanese rickshaw man is as never-ending as a Scotch sermon; there is always a ‘seventhly and lastly’ lying in wait to disappoint you.”