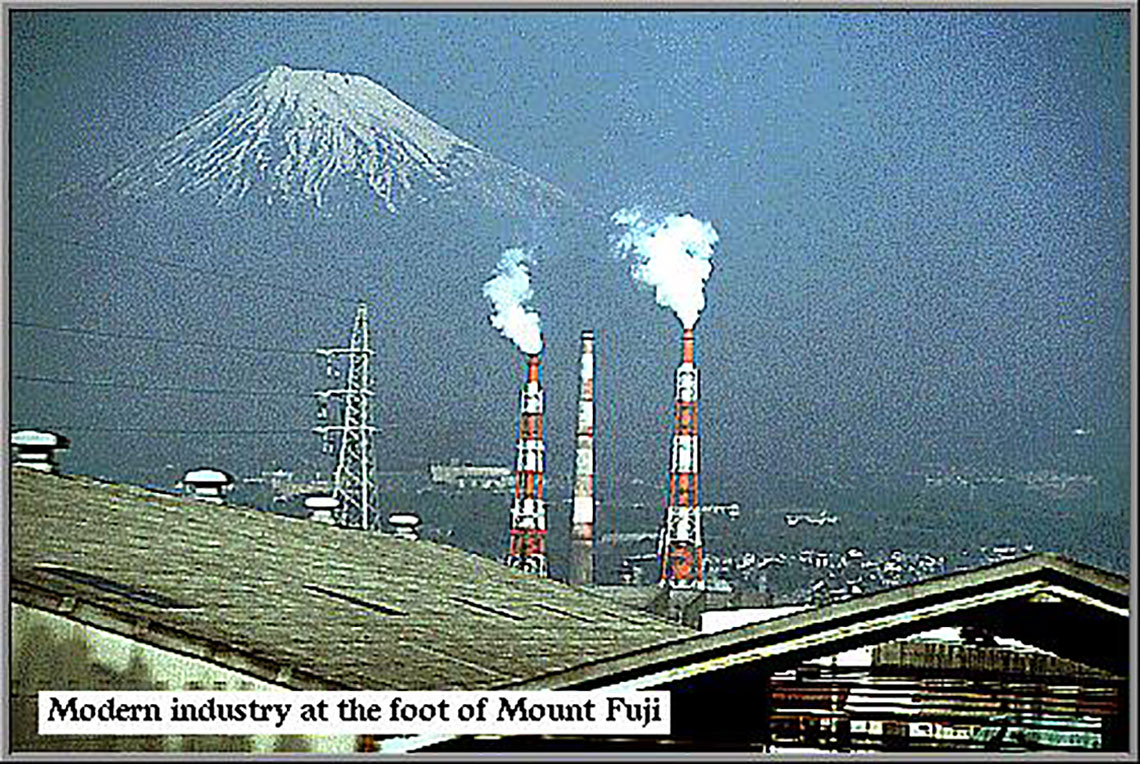

Pollution is endemic in the modern world unless strenuous efforts to prevent it are undertaken. Large numbers of people and industries concentrated in small areas and consuming large quantities of resources are major sources of pollution. Japan certainly fits this description.

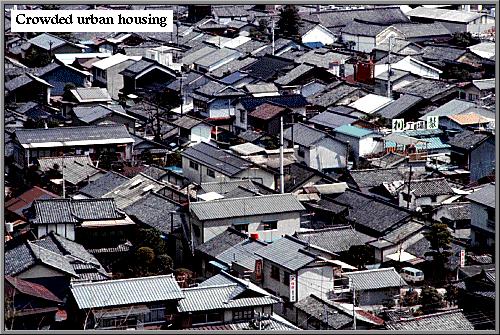

shortage of habitable living space

Immediately after World War II, the primary goal of the government and industry was to promote industrial growth as quickly as possibly. The possibility of pollution was ignored and when it did begin to appear, knowledge of it was usually suppressed and denied. It became an expected social cost of industrial growth and personal prosperity. Eventually, however, the fact of pollution became undeniable. By the late 1960s, policemen in Tokyo were having to resort to oxygen canisters after serving long periods at busy intersections, while evidence of mercury and PCB poisoning emerged in a number of cases along the Pacific coastal region where industry was most heavily concentrated.

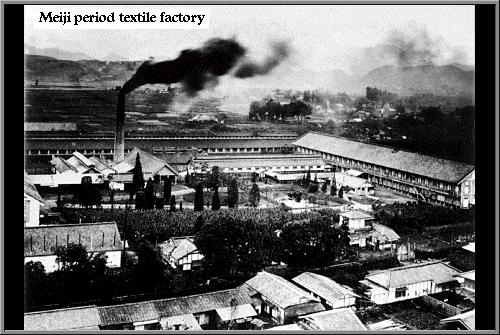

Awareness of pollution actually dates back to the late 19th century when the Ashio Copper Mine in Gunma prefecture, on the edge of the Kanto plain, began polluting its surroundings. Around the turn of the century the mine became one of the largest producers of copper in the world, earning vast amounts of foreign exchange, but it also spewed toxic chemicals such as arsenic into the rivers and promoted flooding by clear-cutting forests in the surrounding hills for fuel. By the time there were strong moves to control Ashio’s pollution, it was falling into economic collapse and the problem gradually dissipated. The government’s policy was to contain the public’s outrage rather than address the source of the problem, a policy that continued until the 1960s.

old textile factories

In the 1960s, the most famous pollution case was the Minamata mercury poisoning case in which a chemical manufacturing firm released untreated mercuric oxides into a rich inshore fishing area. Reports of a strange disease which appeared linked to eating seafood had emerged as early as 1956, but only in 1962 did the government officially recognize what was called the ‘Minamata disease’ or mercury poisoning. In 1973, a civil suit was filed claiming compensation for thousands of victims, including at least 560 deaths, a case which was only settled in the 1990s. Despite an attitude in government and industry in favor of ignoring pollution, the subject has gradually received more and more attention in the community at large. Much of the public’s attention has focused on urban air pollution, smog, noise, odors, destruction of the natural environment (Mt. Fuji was barely visible from Tokyo in the early 1970s), land subsidence in residential areas, waste disposal and, more recently, awareness of the global nature of the problem. In 1970, official government policy had advanced to the point that it recognized that the environment required protection even if it had a negative influence on economic growth. In 1971, the Environmental Agency was established with wide powers to encourage pollution control. It proved so effective that in 1978 the OECD recognized Japan as a leader in pollution abatement and control.

One approach to pollution was to disperse the sources of it. National development plans encouraged industries to move away from the metropolitan centers to the provinces. These plans, including the famous Tanaka Plan (named after Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei), reflected increasing alarm over environmental blight which resulted from policies which favored industrial build-up without full consideration of the consequences.

Today, some of the results of pollution control can be seen throughout Japan. Industry has been more widely dispersed: Nakatsugawa was a quiet post-town in the Edo period, but it is a prosperous industrial city today. Industrial estates were planned and separated from residential areas, and safe waste disposal methods were introduced. Perhaps like any industrial nation, Japan has also benefited as it became a post-industrial nation which exports the industries which are the worst polluters to less developed nations which, like Japan of forty years ago, are willing to value economic growth over environmental quality.