Before 1945

Between 1913 and 1941, Japan evolved a two-party parliamentary system. but since other minor parties were able to survive the system is properly called a multi-party system. The history of parties goes back to the 1870s when government leaders from the former Tosa domain, disagreeing with their share of power, left the government and established a political party with limited, regional appeal. Other parties were subsequently established, but until the Emperor Meiji presented the nation with the Meiji constitution in 1889, these parties generally had a regional basis and were used by individual leaders to pressure the government toward a parliamentary system in which power might be shared. One of the criticisms which was directed at the early parties was that they were not public entities formulating policies which could attract national support and guide the nation as a whole; instead, they were factions which served only limited, private or local interests.

Under the 1889 constitution, one single party began to emerge when it became apparent that political opposition through the lower House of Representatives was possible. By 1900, conflict between the ruling oligarchy and the elected Representatives led to stalemate and one oligarch, Ito Hirobumi, joined forces with a majority of the representatives to form the Rikken Seiyuka” (commonly called the Seiyukai or ‘Friends of Constitutional Government’) which remained as a dominant party until 1941. In 1913, a second stable party, the Doshikai was formed at the national level to offer an effective alternative to the Seiyukai. The Doshikai was later renamed the Minseito. Minor parties on both the left and right wings also arose, but before 1945 they never secured as much as 10% of the popular vote, even after all men were given the right to vote in 1925.

In the liberal 1920s, the parties dominated politics and power. They were, however, continually embarrassed by corruption and by charges that they represented local, partisan, and private interests rather than the national interest. In this period there were a series of assassinations of politicians and their supporters. The last series of attacks in 1932, combined with the rising prestige of the military services, led to the parties’ losing their control of the cabinet. In the next decade, their influence further declined while totalitarian political models based on German and Italian experience gained influence. In 1941, all parties were dissolved and incorporated into a single party, the Imperial Rule Assistance Association. Within this structure, however, the pre-dissolution parties maintained an informal existence throughout World War II and, with the beginning of the Allied Occupation in 1945, they quickly re-established themselves.

After 1945

In the postwar period, the party system has evolved into a very stable system. The main prewar parties, descendants of the Seiyukai and the Doshikai-Minseito, competed for power initially, but their dominance was soon challenged by the rapid growth of socialist parties and the now legal Japan Communist Party. In 1955 the parties which held sway in the prewar period were forced to merge into the Liberal-Democratic Party (LDP)], following the example of the main socialist parties. Since the creation of the LDP, that party remained in control of the government until August 1993. The LDP and the Japan Socialist Party have consistently captured the most votes and the greatest number of elected representatives in national elections. In addition to these two parties, there was the Japan Communist Party and, more recently, the Komeito (or Clean Government Party) and the Democratic Socialist Party, plus a variety of ephemeral parties. In 1993, in a potentially major change, new parties emerged to eject the LDP from supremacy.

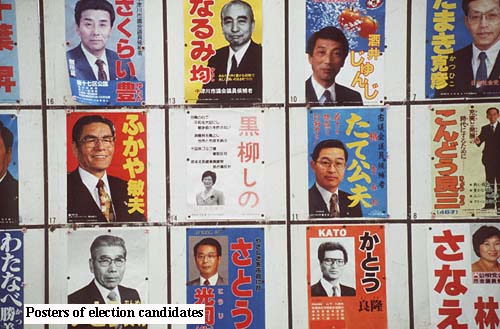

The system is formally called a multi-party system and it produces a plethora of colorful campaign posters. Until 1993, however, it was often described as a ‘one-and-a-half party system’ or ‘the LDP and the four dwarfs’. In other words, the LDP consistently maintained control of the government from its creation in 1955 to 1993. From time to time, the LDP suffered reverses in elections at the national level, but it always held at least a narrow majority in the crucial House of Representatives, where it is decided who becomes the prime minister. The other parties, the four dwarfs, contested elections, but never gained a majority.

Nevertheless, the LDP could not ignore its opponents completely. Before 1993, it was forced to reach out to the other parties from time to time to continue control of the government through compromise. For this purpose, the Komeito (which has been the number three party in terms of election success for many years) and the Democratic Socialist Party have been the parties to which the LDP turned because they are the most conservative.

The Komeito was established by a Buddhist religious group called the Soka Gakkai (the Value-Creation Study Society, which is the lay arm of the Nichiren Soshu sect), but the party has found it impossible to extend its appeal much beyond the confines of the sect despite a formal separation between party and sect. The sect appeals particularly to the upwardly mobile section of the lower middle class, but its size, and the party’s electoral performance, have not changed for a long time. The party is viewed as reformist but within a conservative framework, making it a logical coalition partner for the LDP should the need arise.

The Democratic Socialist Party has remained small, but relatively important because it is supported by the largest national federation of labor unions. These unions are generally enterprise unions which, like their party, are moderate to conservative in their politics.

The Japan Communist Party long maintained a stance which was independent of both the Soviet and Chinese communist parties. However, after Japan began to experience rapid economic growth in the 1960s, it has not been able to gain more than 11% of the popular vote; the collapse of communism in the former Soviet Union cannot be expected to help this party. The Japan Socialist Party is the second largest party but its electoral appeal is limited by its radicalism (it has usually been further to the left than the communist party) and its tendency to indulge in internal factional battles.

In the run-up to the August 1993 election and after, two new parties came to prominence: the Japan Renewal Party and the Sakigake Shinnihon-to. Composed mainly of dissident members of the LDP who were disgusted with scandals and the lack of electoral reform, the parties have enough members to be kingpins in the coalition government which took power in August 1993. Because they are fundamentally conservative and because the LDP remains by far the biggest party, many observers thought that a coalition with the LDP and dominated by it would be likely in the future.

The LDP and its factions

To outsiders, the political party system in Japan might seem to be a mockery of parliamentary democracy. Until 1993, The LDP had been in power nearly forty years and therefore able to arrogantly ignore the wishes of the electorate. This was not entirely the case. Pressure was brought to bear on the party or its members from various directions. The criticism that could be made, however, was that much of this pressure was not subject to public scrutiny or approval. Business interests, for example, have a vast amount of influence and power. The party itself had only a few tens of thousands of members until the 1980s when it announced a policy to expand its membership to one million. These members do not have much power within the party, however.

One factor which was crucial in terms of changes in political power or policy was factions within the parties, particularly within the LDP. Factions in the LDP have been compared with feudal bands of warriors; a single leader who demands and receives absolute loyalty and obedience from his followers. Faction leaders preserve their power and increase the size of their faction by soliciting money (usually from businesses) which ensures electoral success. Electoral success, in turn, gives the faction greater force within the party and control of the more powerful positions in the cabinet including, perhaps, the prime ministership.

Factions, however, can fall from power; scandalous behavior or policies which fail to bring the desired results may lead to political contributions drying up, electoral loses, and defection of faction members to other factions or, in 1993, to new conservative parties. The faction then either changes its leader or recedes to insignificance within the party. In this manner, the major changes in leadership until 1993 occurred because of changes between the relationships of the leaders and factions within the LDP.

Regardless of whether or not the LDP is democratic in its internal structure, it has been forced to change slowly because of demographic changes. From the day of its creation, its major source of voter support was rural electoral districts. However, the flood of people out of rural areas has pressed the LDP to increase its appeal to voters in urban districts. The party is proving willing to pursue the issue of re-drawing the election district boundaries so that urban voters receive a fairer proportion of elected representatives. This would have been unthinkable in the 1970s. The party’s loss of power in 1993 may provoke quicker change, but this was not evident in the months immediately after the election.