A political campaign in Japan is very carefully limited by laws as well as by tradition. Legally, some forms of campaigns common in other countries are prohibited: door-to-door soliciting for votes is illegal, for example. Others forms that are prohibited are more familiar: gifts may not be given to voters (they might constitute bribes) and parties for the entertainment of voters are not allowed (for the same reason). The laws also set very strict limits on other forms of campaign activities. Only a limited amount of money may be spent in national elections and election posters can only be displayed in specified places and may not exceed a certain size.

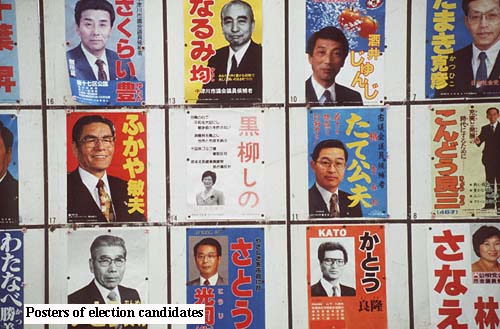

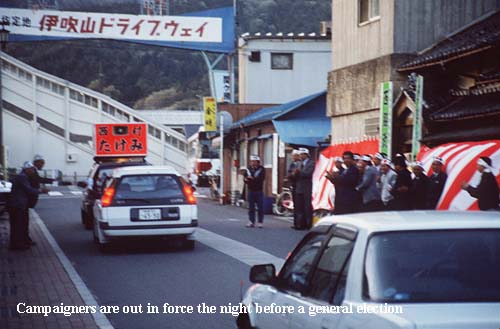

The most visible forms of campaigning are posters pasted to specially erected boards, the handing out of election material in public places, speeches in public venues, and sound trucks which circulate neighborhoods bombarding voters with solicitations from candidates and their supporters. The volume of the solicitations is supposed to be limited, but the limits tend to be ignored as the election nears. Candidates will often alight in public places such as in front of train stations and give speeches to passersby whether they are interested or not.

Door-to-door solicitation is banned because personal contact is felt to have an influence in Japan which is very much greater than in other countries. This is because the Japanese typically place a higher value on what is called ‘human relationships’ (ningen kankei). Before 1945, when the regulations were very different, candidates typically contacted people of influence and relied on them to use their influence to sway voters. Often, these ‘men of influence’ were influential because they held some sort of economic power in a local community: they might have been the landlord of most of a farming village or the employer of a group of artisans. When men of this kind of influence ‘suggested’ how votes might be disposed, there could be little choice in the matter. For this reason, many areas in Japan before 1945 voted 100% for a single candidate.

Another reason for this kind of voting pattern in the pre-1945 period was that a candidate, if he were a member of the ruling party, could promise to deliver (or withhold) the benefits of government depending on the voting record of a district or village. Provision of a school, sewage line, irrigation improvement, road link or railroad extension would depend entirely on election results. This kind of ‘pork-barrel’ manipulation is never far from the surface in most political systems, and is often seen in present-day Japan, but when it was reinforced by ‘personal relationships’ it was overwhelming.

Another factor in the outcome of campaigns in the period before 1945 was the police. The police were administratively under the Home Ministry which usually was headed by a political appointee, a member of a political party. Police were both respected and feared; since they were present at every local level, they made an excellent instrument which could be used to pressure voters in casting their votes. From 1890 until 1924, no election in Japan ever went against the party which controlled the Home Ministry. Today, the police are better buffered against explicit political influence and take some trouble to avoid appearing to influence elections.

Bribery and other forms of financial illegality can be legislated against, but have proved virtually impossible to eliminate. In the post-1945 period, Japan has seen a great deal of bribery, especially by the Liberal-Democratic Party (LDP) and its predecessors although party workers and candidates from all parties have been involved. After every election, hundreds and thousands of election workers and candidates are arrested and tried (the arrests and trials come after the election partly because the police do not want to be seen to influence the election by making accusations during the campaign: since the majority of those arrested are supporters of the LDP, this form of ‘even-handedness’ is open to question). Since the bribe is often in the region of US$5-15 or a bottle of sake and since the average income of Japanese voters is above that of North Americans, one can question the impact of such a level of bribery. What is of more concern is that the amount of money required for even such a low level of bribery is immense if it has to be done on a wide scale. Campaign spending is limited by law, so funds for bribes (and other forms of campaigning) must be raised through questionable means.

This situation has led to a series of scandals involving the ruling LDP party. The LDP has a narrow popular membership as well as a close relationship with the business community. In short, large amounts of money roll in to the party and are used to achieve election success. The Lockheed Scandal of the 1970s and, in the past few years, the Recruit Scandal, the Sagawa Kyubin Scandal, and the scandal surrounding Kanemaru Shin, an LDP kingmaker, have rocked the party, toppling prime ministers from office and, in 1993, led finally to the removal of the party from power.