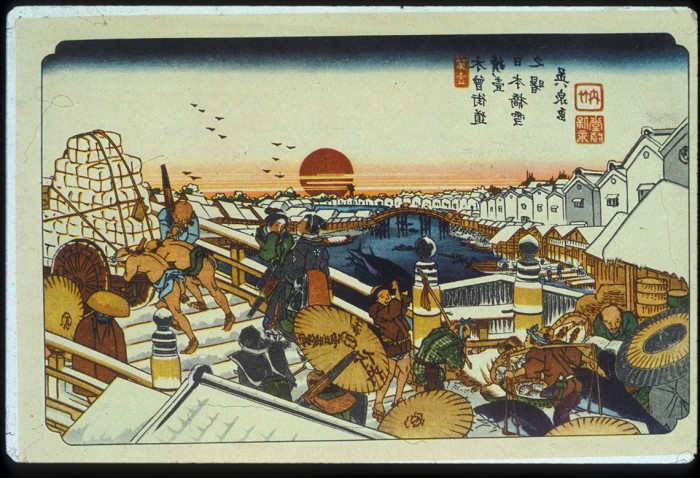

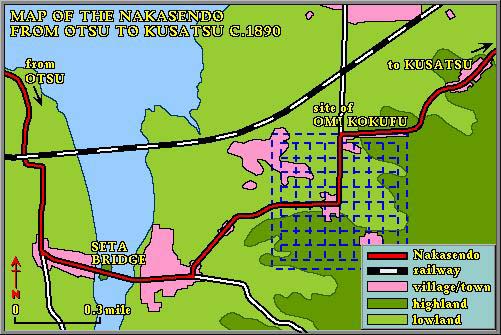

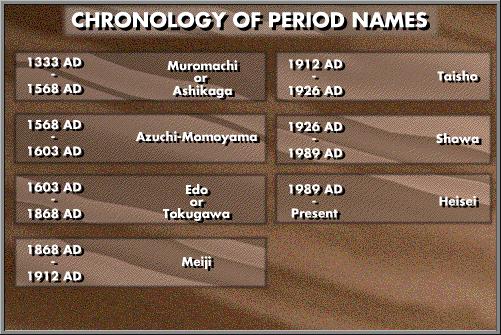

Although the centers of commercial activities were located in the towns and large cities which grew up in the Edo period, the old province of Omi, the area south and east of Lake Biwa, played a large role. The Omi merchants became famous throughout Japan, and very rich too, through their base in jute and other commercial crops. Soon they were seen on a regular basis in large and small communities, trading in jute yarn, mosquito netting, home medicines and clothing. The Omi merchant, shouldering a pack larger than himself, became a stock figure on the Nakasendo highway, and a welcome visitor to homes starved of specialty goods from afar.

Merchants from rural areas like Omi came to fill a very important place in the commercial development of Edo period Japan. The large cities of the Warring States and early Edo periods drew their agricultural and manufactured supplies from the immediate rural areas surrounding them. As the decades passed, however, the cities grew so large that the surrounding areas could not provide all the demands of the cities. Edo in particular was a problem with its population reaching a million by the 1720s, and the district of Nihonbashi was one of the most overcrowded. It became necessary to draw on the production of distant towns and cities. Initially, much of this trade and commerce was funneled through Osaka and the merchants located in the large cities of Osaka, Kyoto and Edo monopolized and profited from the urban growth.

As time went on, the demands of the cities surpassed what the city merchants were able or willing to supply directly. Out in the provinces, such as Omi, which were not too far away from the cities and from the highways, local entrepreneurs who had a bit of capital began to encourage peasant farmers to raise crops which would either be transported directly to the cities, or processed into a manufactured product and then transported. Through the efforts of the Omi merchants, large areas along the Nakasendo changed from subsistence agriculture to commercial agriculture which aimed to profit by raising and exporting its production.

Many of these merchants may have prospered by exploiting farmers in their own village or area. Various governments tried at one time or another to limit merchant activities in rural areas, but without success. One domain tried to ban rural merchants, but failed and then tried to limit the number of items which could be traded and the number of traders. This too failed and the number of legal peddlers doubled in less than fifty years. Soon peasant farmers were purchasing and selling not just necessities like farm tools, but luxuries like perfumes. Commerce, and prosperity, followed the Omi merchants as the years passed.

By the end of the Edo period, Omi merchants, and their cousins in other areas of Japan, had grown immensely wealthy. They were also uniquely situated because they had far-flung interests which brought them into contact with the political and economic changes of the last decades of the period. They often proved quick to anticipate the changes and take advantage of them and became influential in the modern period of capitalist development.