Tracing the path of a bygone highway across Japan, it seems easy to distinguish between the ‘old’ and the ‘modern’ routes. Along the Nakasendo, for example, there are many places where the old and new highways overlap for a while before the two routes diverge. Often this occurs on the approach to an Edo period post-town.

Typically, the ‘old’ road narrows, and passes quietly through a tightly packed group of traditional wooden buildings. The ‘new’ road maintains its three or four lane width, and passes around the back of the town as if trying not to disturb it from sleep. Wakefulness along the modern by-pass is emphasized by a garish display of neon lights advertising modern delights to the car driver, to the outdoor sportsman (notably the skier and golfer), and to the all-night trucker looking for a hamburger and coffee stop. The old post-town, virtually devoid of traffic, says goodnight to the two old men at the liquor store. They have been the only customers all night.

Although real, the problem with this picture is that only two scenes are drawn. In fact, the ‘modern’ road seems to change course, and outlook, every decade or so. Even the ‘old’ road can hardly be described as static, for it too has changed direction more than once with the passing of the centuries.

The earliest ‘roads’ have mostly been lost in the obscurity of ancient, unrecorded times. Most likely they were trails following ridge tops, overlooking the valleys on either side below. Valleys would only be crossed when it was necessary to get from one ridge to another. The reason may have had something to do with safety from attack by man or beast, but equally probable is the fact that the valleys were so densely overgrown that progress was difficult and navigation virtually impossible.

While it is known that imperial troops were moving around the country probably as long as 1,500 years ago, the first official highways are not recorded until the 7th century AD. Even so, the oldest surviving description of these routes dates back no further than the early 10th century. Listings of the post-stations in use then suggest that routes still tended to follow the higher ground. For example, the 17th century Nakasendo follows approximately the line of the 8th century Tosando highway, but with many minor variations of route along the way. One place where the two highways coincide exactly is the section along the ridge at Usui-toge, suggesting that even in comparatively recent times the valley floors near there remained impassable.

It was the expansion of the cultivated area after the 10th century which brought about the clearance of valley floors over much of the country. As this happened, highways began to follow the gentler line of the valleys rather than the more rugged ridge tops. The orientation of the highways changed so that progress was best achieved by crossing from valley to valley rather than from ridge to ridge. Apart from occasional exceptions like Usui-toge and Wada-toge, this seems to have been the case when the route of the Nakasendo was fixed in the early 1600s.

The crossing from one valley into another brought mountain passes, or toge, into prominence during the Edo period. Along the Nakasendo the passes on either side of the Kiso valley were especially feared as being long, steep, and arduous. The route taken was the direct one, however, in the belief that the shortest way to the top was the best.

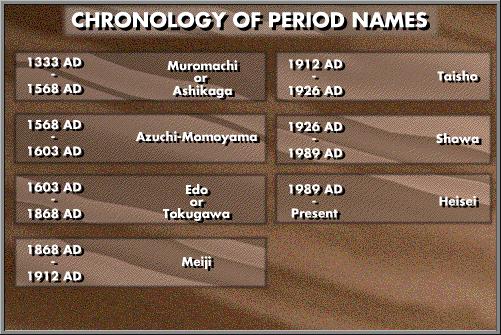

In the Meiji period Western influence brought with it a frenzy of railroad construction and, shortly after, ‘tarmac’ roads for use by motor vehicles. Although the existing highways were followed for the most part by these new constructions, the notion of taking the direct route over the steepest mountain passes was clearly unsuitable for both rail and modern road. The Nakasendo was originally scheduled to be the route for the Tokyo-Osaka main railroad line, but Usui-toge proved too difficult an obstacle and work was re-directed along the old Tokaido. Even today, two powerful engines are required to haul trains around Usui-toge on the main Tokyo-Nagano line. The lesser passes were crossed by some of the early ‘modern’ roads, however, by introducing an approach and descent by ‘hairpin bends’. Unfortunately this construction caused the near destruction of earlier sections of highway, and it is likely that segments of original ishidatami disappeared in the process.

Since World War II, periods of remarkable and sustained economic growth have led to a complete revamping of the nation’s transport infrastructure. From the late 1950s a new highway system was begun which by-passed ‘old’ post-towns to create a more speedy flow of traffic between more important urban centers. Many old post-towns had already lost their trade because they had been by-passed by railroad development earlier. It is along these routes that modern ‘truck-stops’ are usually found today, often just a few hundred yards from the derelict inns and tea-houses of the old post-towns. The hairpin bends of a more recent period also fell into disuse, as modern roads using new construction techniques cut into or under the ancient ridge tops and mountain passes.

Even these ‘new’ roads and (old) railroads are being replaced now by a more modern system of expressways and super-express trains. The aim is to get from major metropolis to major metropolis as quickly and as conveniently as possible. Given Japan’s mountainous terrain the most expedient way is the direct route by tunneling. Such routes follow the ‘across narrow valley and under ridge top’ principle and, while quick, offer only the most fleeting view of the passing countryside. Perhaps in recognition of this, there has been a popular boom in recent years of hiking the trails along ridge tops, and through almost forgotten post-towns along the ‘old’ highways. Is it an irony that the cheapest and most convenient stores to buy hiking equipment are found along the ‘modern’ highways, next to the truck stops?