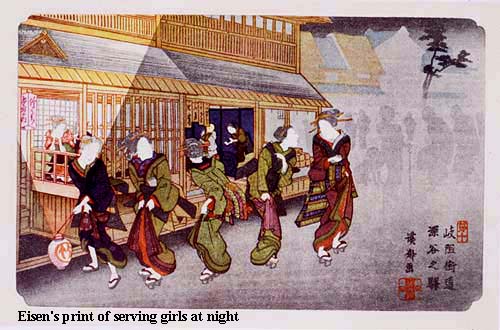

In the 17th century Kaempfer wrote, ‘There is hardly a public Inn upon the great Island Nipon, but what may be called a bawdy-house’. He describes as many as six or seven ‘wenches’ at each inn sitting near the door attracting the custom of travelers. Although officially called serving maids (meshi-mori onna), it is quite clear that their trade included prostitution as well as serving meals.

With the increase in the number of pilgrims and commercial travelers during the Edo period, the number of meshi-mori onna, and the raucous nature of the nightlife tended to increase. In recognition of this, the government in Edo issued regulations in 1718 which set a limit of two serving maids at each inn or tea house on the all the highways. The truth is, however, that there were some post-towns such as Oiwake and Fukaya which had developed a reputation for nightlife and reports suggest some inns kept as many as ten women. Even if there were insufficient numbers of women at any inn, they could always be ‘borrowed’ from neighboring establishments.

Sex with prostitutes was not considered an particularly immoral activity. It was more a question of whether one could afford it. It was considered absurd, however, for people with low incomes to keep more than one woman. The government often issued laws which sought to limit ostentatious spending on clothes and entertainment, but the frequency of such laws suggests that they had little effect on behavior. It seems that laws and penalties regarding prostitution were stricter in China. As Kaempfer concludes,

‘Tis on this account, that the Chinese us’d to call Japan the bawdy-house of China, for this unlawful trade being utterly and under severe penalties forbid throughout all the Chinese Emperor’s dominions, his subjects frequently resorted to Japan, there to spend their money in company with such wenches’.

In Ikku Jippensha’s Hizakurige or Shanks’ Mare, translated by Thomas Satchell, there is an excellent depiction of nightlife in a post-town, Fuchu, on the Tokaido highway well known for its evenings. The two protagonists, Kitahachi and Yajirobei,

took a room at an inn in Temma-cho, after which Yaji went off to find his friend in the town, where he succeeded in his plan for raising some money and returned to the inn greatly elated. Whatever happened they felt that they must spend the night at Abegawa-cho, of which they had heard so much. Accordingly they both made their preparations and summoned the landlord.

‘We want to go sight-seeing in Nicho-machi,’ said Yaji, ‘Which is the way there?’

‘Is it far?’ asked Kita.

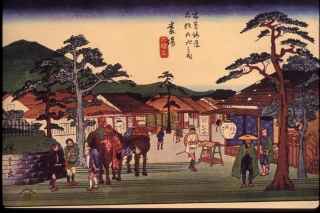

‘No, only about a mile and a half,’ ansered the landlord. ‘I’ll hire horses for you, if you like.’

‘Ah, that would be good,’ said Kita.

‘It will be fun going to buy a girl on horseback,’ said Yaji.

Finally, they set out on horesback.

This Abekawa-cho is in front of the Abekawa Miroku [temple]. Turning off the main road you come to two big gates, where you must alight from your horse. Inside are rows of houses, from each of which comes a lively sound of music, meant to attract people to the house. In fact it is much the same as in the Yoshiwara quarter in Edo.

Visitors to the town were walking about in cotton kimono with crests and with towels laid loosely on their heads, accompanied by teahouse maids, whose clogs made a loud sound as they dragged them along. These all looked very respectable, as most of them wore wide skirts and all had cloaks. But among the townsmen, those who had only come to look on, there seemed to be a competition as to which should wear the most stylish aprons. Some of them were carrying straw bags suspended on sticks laid across their shoulders. Moving in a constant stream as they did, they look like people who were going to worship an image of Buddha. It was impossible to know to what class they belonged or to tell the state of their fortune. . . .

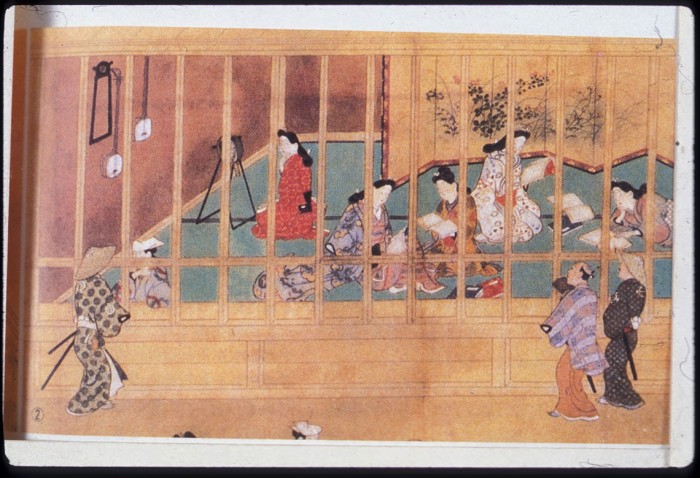

Some of the same [lower] class were standing in front of the cages.

‘That girl’s face over by the wall there,’ said one of them, ‘is like the saintly mask of Sengen [goddess of Mount Fuji]. There, she’s got up and gone now. She’s very short, isn’t she? She’s like the bamboo grass that Kajiwara’s horse bit off, only half grown.’ [Kajiwara was an 11th century samurai given a famous horse.]

‘The dresses in this house,’ said another, ‘are like the lacquer-boxes in Shichiken-cho.’

‘Let’s go in somewhere,’ said Yaji.

‘Wait a minute,’ said Kita. ‘The girls all have different prices — some of them are one bu, some ten momme, and some two shu. I’ll have that one over there by the wall. She’ll be ten momme [the cheapest], I expect. What’s the name of that place? Shinonoya. And there’s the Chojiya, and this is the Yamamotoya. But what do you do to get in? I don’t know how they manage things here.’

While they were wondering about in front of the cages, they saw a guest arrive and go in.

‘Oh, oh! I see now,’ said Kita. ‘Let’s go in here. Yaji, have you chosen one?’

‘Yes, yes,’ said Yaji. ‘Come on.’ So they went in together.

‘Welcome!’ said a young man at the entrance. ‘Please come up.’

He conducted them upstairs and soon led them to the room of the girls they had selected. Looking round they saw there was a harp in the alcove and also some flowers. Altogether it was like a small house in the Yoshiwara at Edo. Apparently it was the custom to pay some drink-money at this stage of the proceedings.

‘Will you have some sake?’ asked the young man.

‘Yes, bring some sake,’ said Kita.

Meanwhile the two girls they had selected had come in. Yaji’s, whose name was Kozasano, was dressed in a wadded silk robe, with a striped satin girdle and a sky-blue overmantle; Kita’s, whose name was Isagawa, was dressed in a striped crep-silk robe and had gold embroidered girdle, with a black silk cloak. Both of them had silk lining to their clothes. A plain wooden tobacco-box was brought in and put before them.

‘Welcome’ said Kozasano.

‘How careless, ‘ said Isagawa. ‘That girl hasn’t put any tobacco in the box. Kosame! Kosame!

‘Well girls,’ said Yaji. ‘Come a little closer. Here, young man, be quick with the sake.’

‘It’s coming, your honour,’ said the youth. He went out and soon came back with a

sake bottle and cups and some comestibles. The formal cups of sake

having been exchanged, Yaji offered the cup to the young man.

‘Have a drop,’ he said.

‘Thank you,’ said the youth.

At the same time Yaji gave him a silver coin, which he took and went out. . . .

‘Come more over here,’ said Kita [to Isagawa], ‘and have a cup.’

‘Let me pour for you,’ said Isagawa. . . .

Just then there was a noise in the passage, with the sound of many voices raised in dispute, and finally the persons disputing went into the next room.

‘What’s the row?’ asked Kita.

‘It’s nothing,’ said Isagawa. ‘They’ve found a bad guest and brought him here.’

‘Ah, that’s amusing,’ said Yaji. ‘Let’s have a look.’

He pushed open the sliding doors a little and peeped into the next room, where a large number of girls had surrounded one of the guests.

‘Why do you never come here now?’ they asked.

‘You’re always going to the Chojiya now,’ said another girl, ‘and you’ve got no reason for it. You’ve made Tokonatsu quite angry.’

‘Well, look here,’ said the guest, who seemed to be a country fellow. ‘The day before yesterday and yesterday I was coming, but I had so much to do that I couldn’t get here. Then my uncle asked me to accompany him to the Chojiya, and I went, but as I am under a vow to Tokonatsu I swear by Nitten I did not allow my heart to be turned.’

‘Nonsense!’ cried the girls. ‘You went with Hanayama of the Chojiya. We know all about it.’

‘No, no, that’s not true,’ said the guest looking hurt. ‘You mustn’t say such things.’

Then an elder girld of the name of Tokonatsu came in. She had thrown a mantle over her shoulders and came in solemnly carrying a pipe and a tobacco pouch.

‘You are welcome, Master Yatei,’ she said.

‘I’m sorry I haven’t been able to come and see you lately,’ said Yatei. ‘You must excuse me.’

‘There’s no excuse for you,’ said Tokonatsu. ‘I’m the oldest here, and the girls call me elder sister. How do you suppose I’m going to maintain my position here if I’m put to shame like this? I’m going to punish you just as a warning to other false guests like you. Here, Natsugiku, bring that razor.’

‘What are you going to do?’ asked the guest.

‘What am I going to do?’ said Tokonatsu. ‘I’m going to cut off you hair.’

The razor was brought and the girl stood up to carry out her threat.

‘Spare me, spare me,’ cried the guest as he tried to shield his head. ‘Wait, wait.’

‘There’s nothing to wait for,’ cried the girls.

‘I can’t let you cut a hair of it,’ said the guest. ‘Forgive me, forgive me.’

‘Forgive you, indeed!’ said Tokonatsu.

‘Well, but look here . . .’

‘We must cut it off.’

‘Here, here,’ cried the guest. He tried to run away, but they all got round him and caught hold of his head, whereupon all his hair came off. In truth the man had very little hair of his own and was wearing a false queue and side locks, which all fell off when they pulled it.

‘There,’ said the man, feeling his head, ‘You’ve pulled off all my hair.’

At that all the girls burst into laughter. ‘Ho-ho-ho!’ they laughed.

‘It’s no laughing matter,’ said the guest. ‘Give me my hair and I won’t go to the Chojiya again.’

‘I don’t know anything about your hair,’ said Tokonatsu.

‘Natsugiku’s hidden it,’ said the guest. ‘Please give me my hair quickly.’

‘Will you promise ot to go to the Chojiya again?’

‘Yes, yes. I won’t go again.’

‘Solemnly promise?’

‘By Ten Shoko Daijingu [the sun goddess] I promise not to go again.

”Then give him his hair, Natsugiku,’ said Tokonatsu.

Thus on Tokonatsu’s order the hidden hair was produced and handed to the guest. . . .

Then some sake was brought in to seal the reconciliation and there was a lot

more talking and laughing.

Yaji and Kita laughed till their sides ached. ‘That happens all over the place,’ said Yaji, ‘but it’s very amusing. It was only last spring the Ikku was tied up by Katsuyama at the Nakadaya although he doesn’t like people to know about it.

Then a maid came in. ‘Shall I spread the beds?’ she asked. ‘Please move a little over here.’

Kita went with his companion into another room, and the maid spread the bed, and in a short time they were asleep. But their dreams were short, for the dawn soon came, with its parting, Yaji got up, and Kita came in rubbing his eyes. Their companions accompanied them downstairs, where all were assembled, and after a hurried farewell, they hastened to Temmacho, to find their breakfast at the inn ready for them. [page 81-87]

Although not great literature, Shanks’ Mare gives a good idea of a typical evening which a pilgrim or other traveller might anticipate on the highway.