The idea of planting trees along the roadside to provide shade for travelers had occurred to the Chinese when they developed their highway system more than 2000 years ago. Almost certainly the idea was copied by the Japanese, along with all other features of Chinese highways, when they laid out their own highway system at the end of the 7th century, . By the time that the highway system was rejuvenated in the early 17th century by Tokugawa Ieyasu, however, it seems that most of these trees had either been cut down or had otherwise disappeared. He ordered, therefore, that trees be replanted along the whole length of the new highways, as they had been in the past.

The main purpose of these namiki (literally ‘trees in a row’) was to provide protection to travelers against the elements. This included primarily shade from the sun, although the trees also served as a windbreak, and offered some degree of shelter against rain and snow. Namiki had the additional function of marking the road and of binding the road surface as a protection against landslide and earthquakes. In addition, the leaf litter from the trees was a useful source of green manure for villagers along the highway, who had the task of regularly sweeping the roads before major processions were to pass.

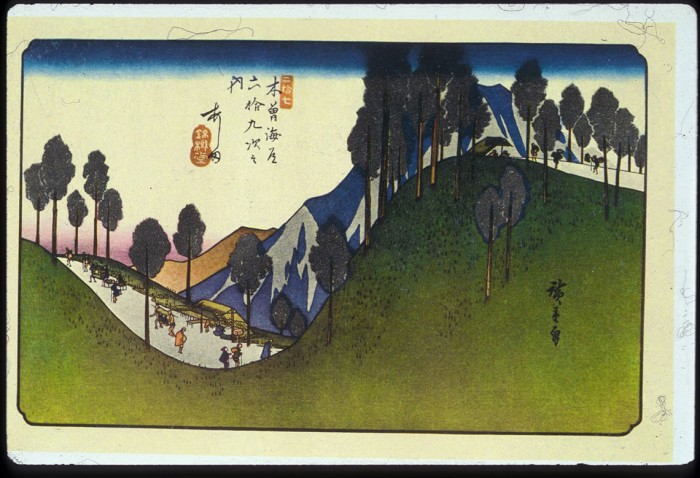

The type of tree to be planted was not specified, but generally conifers were preferred for their fast growing nature and suitability to local soil and climate conditions. The broad canopy of pine trees made them popular, but Japanese cedar and cypress were also very common. Among deciduous trees gingko was generally preferred, especially near Edo, but cherry and maple were sometimes planted for their aesthetic appeal. As a landscape feature, the Japanese were not slow to recognize the artistic appeal of these beautiful, aged avenues. Many of Hiroshige’s ‘road’ prints, for example, are dominated by namiki.

This point was not lost on early Western travelers around the country. Captain Blakiston, describing his journey across north-east Japan in the early 1870s was moved to make this plea:

It is to be hoped that the unsparing and barbarous hand of an impoverished government will not be laid on the pine-trees skirting the old highways of the country, and that this great feature in the scenery of Japan will not be civilized off the face of the earth. . . After the almost bloodless revolution which changed Japan from a feudal to a monarchical government, it should be the study of those in power to retain some of the time honored features of a state which has passed away.

Unfortunately, Blakiston’s plea went apparently unheeded. Writing thirty years later Basil Hall Chamberlain noted that after the introduction of telegraphy into the country the Japanese began to hew down these monumental trees in their zeal for what they believed to be civilization. The telegraph poles would, they thought, show to much better advantage without such old-fashioned companions.

Although Chamberlain further notes that it was mainly the Tokaido which had been affected by the ‘official Goths’, and that the other highways had been largely spared, the fact is that today relatively few of these original stands of trees remain. Along the Nakasendo it is true that five or six trees together can still be seen along various sections of the route, but longer ‘avenues’ are rare. The best surviving examples are probably the trees which line the highway approaching Ashita post-town (where the modern highway has recently been realigned in order to preserve them), and along the section of highway still used by modern traffic approaching Annaka post-town.

Unfortunately, all to often the modern ‘Goths’, albeit with the best intentions, have spoilt the effect by strapping brightly colored bands around the trees with the message ‘this is an original namiki – preserve our cultural heritage’. The good news is that, in areas where local authorities are rediscovering the potential value and cultural merit of preserving the original highway, new trees are once again being planted to replace those which have disappeared.