Kyoto holds a unique position in Japan as the ancient, imperial capital and the cultural center of the nation. It was because of these reasons that the Japan specialists who advised the American military authorities during World War II counseled against bombing the city, although it had been targeted at one time as a site for dropping an atomic bomb. These legacies contribute to the severe problems which arise when it comes to developing or redeveloping the city, since so much of the ‘old’ is inappropriate to the needs of a modern metropolis.

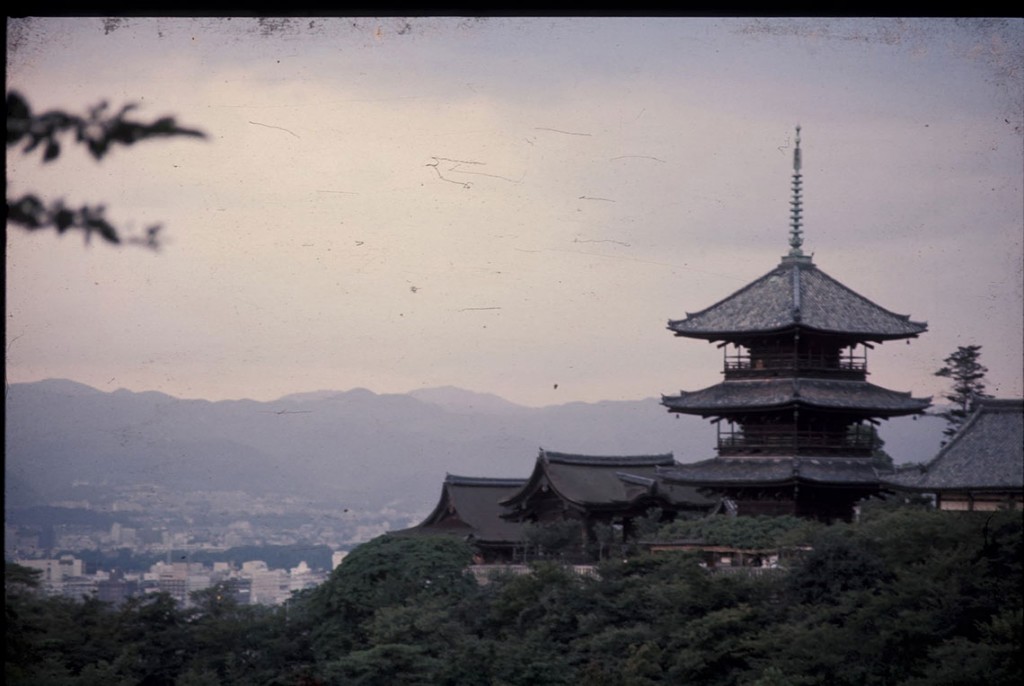

At the present time, the question centers on whether a 20-story hotel should be permitted to be built in the central business district. Like most urban areas in Japan, Kyoto has been a low-rise city for most of its life. A tall tower was built in front of Kyoto Station, rather similar to towers in Kobe and Seattle, but otherwise, few buildings rise above eight or ten stories. The skyline has been dominated instead by clear views of hills and mountains to the north, east and west; by the pagodas of the Buddhist temples of Kiyomizu and Toji; and by the low, graceful roofs of the Nijo Palace, headquarters of the Tokugawa shogunate’s representatives to the emperors, and Nishi-honganji and Higashi-honganji. Throughout the modern period until the 1980s, Kyoto was sedate, graceful and secure in its cultural supremacy.

Kiyomizu

The city did grow, however. Like many cities in the 1970s, it got rid of most of the streetcars which were a convenient means of transport before automobiles crowded the streets. Slowly buildings pushed higher and land became more expensive. The open farmland on the way to Osaka gradually filled with suburban developments.

Finally, in the late 1980s, a consortium of prominent businessmen proposed building a 20-story, 5-star hotel which would be visible from nearly anywhere in the entire valley. The economics behind the proposal were clear: tourism was rising and people would pay whatever was charged. Kyoto was the old, traditional center of Japan and worth any amount of money to see. A high-rise hotel would not only pay for itself, but would lead the city forward into a new, more modern era. The future beckoned and business interests responded.

Opposition to the plan was instant and united many different groups. Traditionalists object to the spoiling of the cultural foundation of a nation already overly modern. Buddhist temples objected because it would destroy the aesthetic splendor that is unique to Kyoto. Even some business and tourism interests questioned the wisdom of a project which would detract from the sense of tradition which draws tourists to Kyoto from all over Japan and far beyond. The debate over this project, and a similar proposal for the re-development of Kyoto station, has continued to rage through the early 1990s.

Despite the fact that change is taking place, the pace of change in Kyoto is slow compared to many other Japanese cities. The people of Kyoto are justifiably proud of their rich cultural heritage and will doubtless continue to argue long and hard over future developments.

Kyoto