There are many foreign workers in Japan although it is difficult to say how many because large numbers are present illegally. Estimates of illegal immigrant workers ranged from 100,000 to 400,000 in 1994, but since the immigration authorities do not seek to check into the problem too thoroughly, any number is a mere estimate. This is a sharp change from twenty years ago when there were far fewer foreigners in the country and none who were unskilled, manual laborers.

The Japanese labor market has been closely regulated for most of the post-1945 period. Initially, there was a labor surplus, but even when that disappeared in the early 1960s, the small number of foreigners who worked in the country were employed by foreign firms or because of their special skills. This type of employee, skilled and highly paid, increased quickly in the 1980s as the Japanese market became more internationalized and open. These workers are a highly mobile group who present few problems for Japan (although they may have some difficulty adjusting to the country).

At the same time, the labor shortage became more severe and soon it was difficult to find Japanese workers who were willing to undertake dirty, physically hard, and often dangerous jobs in construction, road working, and factory cleaning. Word spread in foreign countries and soon thousands of young men who were willing to undertake work that young Japanese would not were arriving from various Third World countries. Today, you can find them scattered throughout Japan, but they congregate in the major cities. In Tokyo, many of them gather daily in Ueno Park to talk and to be approached by potential employers while on Sundays the English-speaking Catholic churches are crowded with Filipina maids.

In addition to this kind of immigrant worker, there are substantial numbers of women who are brought to Japan and, often, forced to work in the entertainment business. Alternatively, since the level of wages is so high for Japanese workers, many Japanese and legitimate foreigners bring in maids from Thailand or the Philippines, but most of these too are illegal.

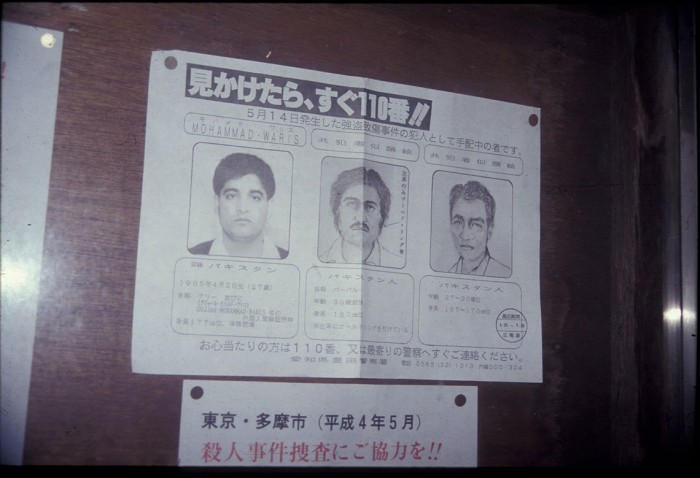

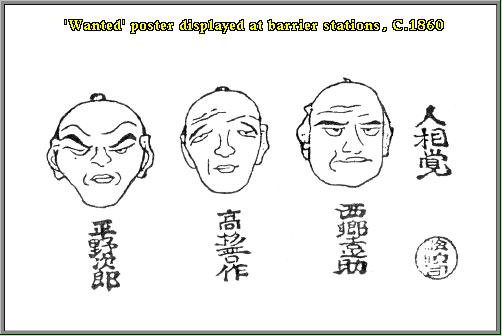

Illegal immigrants pose some serious questions. Rumors frequently circulate that the immigrants are serious crime problems and although it is possible to find wanted posters with pictures of foreigners at police stations, the rumors usually are proven to be no more than that. The posters look little different from Edo period wanted posters. Still, the immigrants present an unsettling challenge to assumptions that Japan is a stable, orderly, and homogeneous society. Often they are put at risk because they are illegal and can not approach the authorities when they are attacked, forced into prostitution, or exploited and mistreated. How should society deal with their legitimate problems? The simple answer, to arrest and deport all illegal immigrants, is not one which the industries which rely on such workers want to see.

Aside from the highly skilled legal employees hired at the top end of the economic scale, there are also some legal immigrant workers with relatively low skills. These are often children of Japanese who emigrated, primarily to South American nations. These workers have recently been allowed to return to work in Japan for up to two years in recognition of their Japanese roots. The number of such immigrants has increased quickly in recent years as the economic conditions of their home countries, especially Brazil, have continued to worsen. The assumption has been that because they are descendants of Japanese, or married to descendants of Japanese, they will fit into the society effortlessly. They may fit in more smoothly, but cultural differences are very noticeable.

In rural areas where depopulation has been a problem, the few young men who are willing to remain on the farm commonly have difficulty finding wives. There has been a small boom in arranging marriages between these men and foreigners, especially mainland Chinese, who are assumed to be hardened to the rigors of rural life. With language difficulties, cultural differences, and the proverbial domineering mother-in-law, these marriages frequently flounder, leaving the women in an awkward position.