The first lord of Hikone, Ii Naomasa, had been one of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s most loyal and trusted generals. As a reward for his services the Ii family were entrusted with a hereditary position of high status and authority as fudai daimyo in the Tokugawa shogunate. The Ii daimyo, otherwise known by their honorific title of Kamon no Kami, was an automatic member of the council of ministers who

advised the shogun on all aspects of government, and was one of the few eligible to fill the post of Tairo, or chief minister.

Ii Naosuke was the 14th son of the 11th lord of Hikone, Ii Naonaka. Born in 1815, his lowly position in the family meant he had the

leisure to engage in a variety of pursuits befitting a samurai of his class. From his modest villa outside the gates of Hikone castle he spent his time in the study of Zen, the art of quick-draw swordplay, and, his passion, the tea ceremony. At the age of 32, however, his life took a most unexpected and dramatic turn. His eldest brother, now the 12th lord of Hikone, summoned Naosuke to Edo. There he was informed that he was to be appointed heir to the Hikone lordship since his brother, Naoaki, was childless. Following the common practice of the time, all Naosuke’s other brothers had been adopted into other daimyo families. He would therefore have to remain in Edo until his eldestbrother either died or produced a legitimate child heir.

In 1850 Lord Naoaki did indeed die childless and Naosuke, at the age of 36, became Kamon no Kami and 13th lord of Hikone. As a member of the council of ministers Ii Naosuke soon became involved in some of the most difficult crises the Tokugawa shogunate had ever faced. In 1853 Commodore Perry steamed into Edo Bay with his fleet of ‘blackships’, demanding that Japan open up to foreign trade. This event sparked off a bitter debate in Japan between those who supported the opening of the country and those who were opposed. Naosuke originally proposed the strengthening of national defenses, apparently siding with the exclusionists. He later reconsidered, however, and in a private submission to the shogun advised that the time had arrived for change and that treaties should be signed with the foreigners while the opportunity was still available for favorable terms. As the debate intensified the issue was thrown into further confusion when the shogun, Iesada, died suddenly in early 1858 without an heir to succeed him.

In such times of national emergency it was customary to revitalize the post of Tairo, or chief minister, and Naosuke was duly appointed according to his hereditary right. In effect he had become the sole executive of government, and the most powerful man in Japan. The council of ministers meanwhile had been split over the choice between two candidates for the next shogun, who could be nominated from one of the three collateral houses of the Tokugawa family. One candidate was Tokugawa Yoshitomi, a boy of just 12 years but closest to the direct line of descent. The other was the mature and intelligent Hitotsubashi Yoshinobu, son of Nariaki the lord of Mito and one of the leading exclusionists in government. Naosuke, already known for his foreign sympathies, decided in favor of Tokugawa Yoshitomi (now renamed Iemochi) and thus deepened Lord Mito’s emnity toward him.

With pressure from the foreign powers still mounting to sign a commercial treaty, Naosuke made another unilateral decision. He agreed to the treaty, but first had to seek formal permission from the emperor in Kyoto. The emperor delayed his approval, however, since he had fallen under the influence of the increasingly anti-shogunate, exclusionist faction. The slogans ‘revere the Emperor’ and ‘expel the barbarians’ were now merged by this powerful group opposed to Naosuke and the new shogun. The reaction of Naosuke was dramatic. First he determined to sign the treaties with America, and later with England and France without the emperor’s permission. Then he opened the port of Yokohama to foreign trade, and in early 1859 he dispatched a Japanese ambassador to the United States. His opposition were quietened, temporarily, by the simple expedients of execution, imprisonment or banishment. More than one hundred samurai were dealt with in this purge (known as the Ansei Purge), including Nariaki, the lord of Mito, who was placed under house arrest.

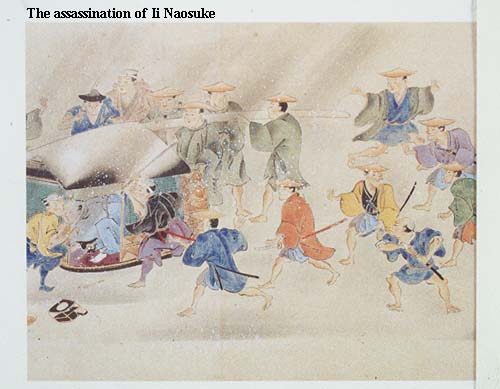

Ii Naosuke, was killed by these radical swordsmen in 1860

The apparent high-handedness of Naosuke’s actions, and his clear insult to the emperor and to the House of Mito (a Tokugawa collateral) left him with few supporters. Few were surprised, therefore, when Naosuke was assassinated by 17 ronin from Mito on March 3rd, 1860. Snow was falling in the early morning as Naosuke was being carried in a palanquin from his mansion near Edo castle to the shogun’s court. His attackers waited near Sakurada Gate, their swords hidden under snow capes. Surprising Naosuke’s bodyguard they quickly broke through to the palanquin, killing its occupant before he had time to react.

Although the news of his death spread quickly, it was almost two weeks before the Shogun’s court made any official announcement. By this time the exclusionists were already finding their way back to power, although triumph for Nariaki was short lived since he too died in September the same year. The other irony is that Naosuke’s successors in government could not overturn his policies of openness to foreign trade and intercourse. Indeed, even after the Restoration of the emperor in 1868, the policies of Naosuke continued to set the pattern for Japan’s drive toward modernization. Although the house of Ii remained discredited for many years after Naosuke’s death, modern reappraisal sheds a more favorable light on this decisive man who lived in a time of political uncertainty and indecision.