Fire was a constant worry before the advent of new building materials and remains a major concern today.

The traditional building was mainly constructed of flammable materials. The basic structure was of wood with the walls woven of bamboo or other material and covered with mud and plaster. Floors were wooden or wood covered over with straw mats (tatami). Roofs were often made of thatch although baked tiles were also used, especially in large structures or in response to the danger of fire. Stone was used sparingly, mainly for foundation work. After standing for a few years or decades, a building of this nature would blaze fiercely if set afire.

The home was the location of many fires. The cooking stoves, heating devices (hibachi), tea water heaters, bath heaters and so on were all open fires fueled by charcoal, wood or straw. Carelessness or lack of attention could easily result in a fire. In addition, natural disasters such as storms or earthquakes could start one or more fires. Even as late as 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake set off numerous fires over a wide area of Tokyo and Yokohama, burning most of the old sections of the cities and killing over 100,000 people. The initial movement of the earth shook apart a few structures, but for every one shaken down, a hundred or a thousand burned in a howling holocaust in the next few days. Even today the greatest worry in a large-scale earthquake is the fires that will inevitably follow the tremors.

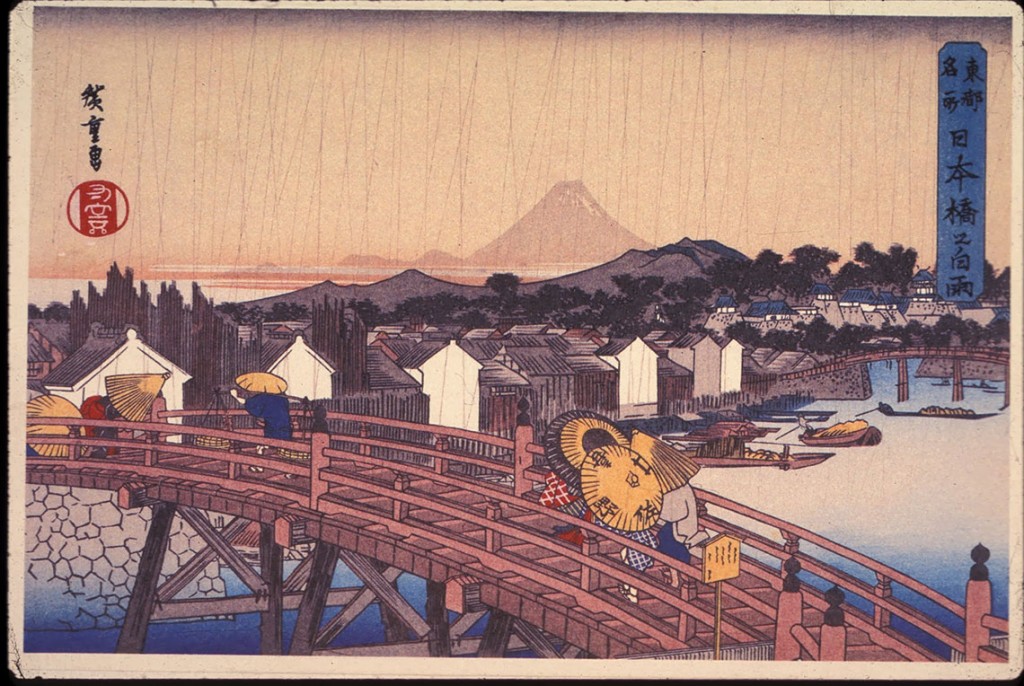

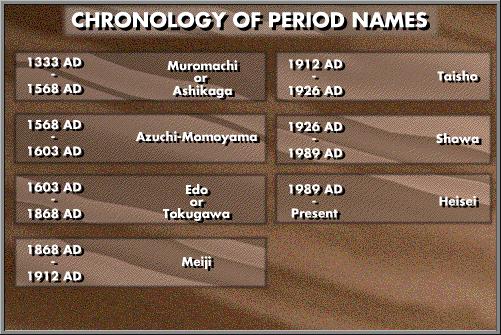

Fire was so frequent that Edo was famous for its ‘Flowers of Edo’ (Edo no hana), the fires which occasionally swept through the city, erasing vast tracts. In the middle of the Meiji period, some districts in Nihonbashi in Tokyo were burnt over three times. In order to counteract fires, companies of fire fighters were established. Their primary mission was to starve the fire of fuel; they would quickly pull down houses and open up fire lanes to prevent further spread of the fire. In the late Edo period when the city had about a million residents, there were around 14,000 professional firemen, including the artist Hiroshige before he escaped full-time into the business of art. These companies have, of course, been replaced today by a modern and efficient fire-fighting establishment, but the skills of the old fire-fighters are maintained by organizations which present public demonstrations each year. Wearing thick, fire-resistant coats and clothes of the Edo period, the men scramble up tall ladders held steady by the rest of the company. Once on top, they perform acrobatics such as were useful in actually fighting a fire.

One of the other hold-overs from the past is a tradition present in many urban neighborhoods of fire warnings for the general public. These are either broadcast over a public announcement system in the evening around bedtime, or someone will parade through the streets, slapping together wooden clappers and shouting Hi no yoshin (‘Beware of fire’).

Along the Nakasendo, it is difficult to find a home or inn that dates back more than 150 years and this is mainly due to fire. Even though many an inn or former inn claims roots stretching back to the late 16th century, most have been destroyed by fire during the nineteenth century. Usually rebuilt on the same pattern as before, the inns appear little different, although some post-towns have insisted on fireproof walls between buildings. Many of the inns have open fire pits with the smoke being vented straight up through the rafters to the roof. The walls and timbers which were bright white or yellow when new are now a deep glossy black where they are rubbed down and thick, accumulated soot everywhere else.

Central part of the inn

Most towns and villages along the Nakasendo still maintain a volunteer fire department, unless it is one of the few towns which has grown to small city status and has a professional fire service. The volunteer fire stations are clearly identifiable by the 25-30 foot tower with a loud speaker and a large bell standing beside a small garage with a small, often antique fire engine. Nearby will be a house for the volunteers to gather on a weekend to talk about techniques or, after a fire, for a celebration of a job well done, hopefully. The volunteers now form a young men’s association and may do most of their group activities through the fire department. With rural depopulation, however, some stations have difficulty mustering enough young men for the task, so any fire will claim at least one complete house. Most of these small departments are called out about twice a year, arriving as quickly as possible on the scene before the professional services reach them to assist.

During the Edo period, the post-towns might have seen several hundred travelers who would be anxious for a relaxing drink of sake after a long day on the road. If they fell to smoking or became rowdy while cooking some fish around the fire pit, fires could easily break out. It was no surprise that more than one post-town had severe punishments for anyone careless enough to cause a fire.