Festivals in Japan are many and varied, and in recent years, they have become popular again after experiencing disapproval and obscurity in the decades immediately after 1945.

Many festivals are connected with the Shinto religion or have roots in the feudal periods, such as Boys’ Day. Because the values or attitudes embedded in them have been accused of being undemocratic and authoritarian, the festivals were strongly disapproved of after 1945. Male chauvinism of Boys’ Day is a good example. Other festivals bring the community together and effectively underline the unity of the community: while this might be viewed as being a healthy way of restoring the social fabric which may have become strained in the previous year, it might also be criticized for subjecting the individual to the dictates of the larger community.

In recent years festivals have revived in popularity. This revival was partly due to a restored sense of national worth as the Japanese economy out-performed the rest of the world in the 1980s. It also has to do with a revival of interest in local affairs in general: television programs frequently travel to small towns and cities for folk song contests, studies of local flora and fauna, or festivals themselves.

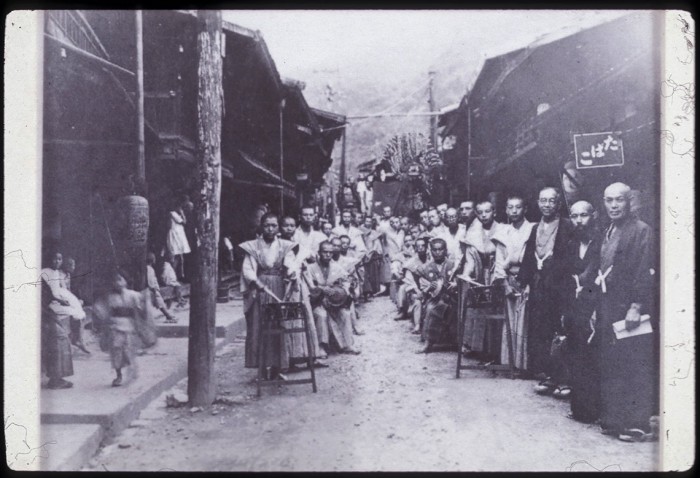

There are a huge variety of festivals, many of them going far back in time to periods when local areas were isolated from each other and when the festivals sometimes reflected local idiosyncrasies and oddities. Some of the festivals remain of local interest only while others are very large-scale and pretentious. Every community, for example, has a festival in the summer which features a parade through the streets by the children, dancing, and decorations in the streets. The Gion Festival, on the other hand, is a massive recreation of the Edo period in Kyoto with huge floats weighing many tons pulled through city streets (when there were trolleys running on the streets the electric wires had to be taken down), large numbers of people dressed in samurai clothes, and parades of geisha. While the Gion Festival is restrained, following the general tenor of life in Kyoto, some of the festivals in Tokyo at the other end of the Nakasendo are rowdy in the extreme. Floats from the Kanda Shrine (they contain the gods for the day) are carried on shoulder through the streets here, but with their great weight and liberal doses of sake for the carriers and with loud cries to make the load lighter, a measure of rough violence is possible. Large city festivals, however, are generally very well controlled since any damage done would boomerang back on the festival itself.

Kanda Shrine

This is in contrast to many small town festivals. Here too god floats are often carried through the streets, paying visits to this home and that shop. But here, the carriers and all the villagers or town people know each other. They also know who has been naughty and nice. When a float calls on a shop, if the shop keeper has been cheating his public, he may find that the float gets carried away and causes damage to the shop. This relates to the role of festivals as restorers of the social fabric. Damage to a shop conveys a clear message to the owner: you have done the community wrong during the past year and should mend your ways in the future. Blame for the damage cannot be fixed to a god, so it is passed over, but the message is clear without the necessity of an actual confrontation between the shopkeeper and his customers.

Many festivals are connected with the agricultural cycle and these are usually Shinto, the religion that is most closely connected with fertility. Some of these can be very bawdy and lewd. Other festivals, like the summertime Obon festival, are Buddhist in origin. Obon is the time when ancestor spirits return to this world to be reunited with their families for three days. Properly treated, fed and wined, the spirits will help the family in the coming year, but ill-treatment may bring trouble.