Politics changed sharply at the end of the Edo period (1603-1868): the period came to an end. But the fact that the period came to an end, after 250 years of stability and continuity raises the question Why?

Historians approach the question from two directions. One is perhaps more obvious: Westerners came and their coming put pressure on Japan which forced change. The other is an approach from a domestic angle: there were occurring in Japan a variety of changes which pushed the system into extensive changes that in turn dictated the end of the Tokugawa political system. Neither approach is satisfactory by itself. Internal developments contributed powerfully to the end of the period, but pressures from the West were present and were crucial too.

Takayama Hikokuro was one of many samurai who, from around 1800 onwards, believed that the emperor deserved greater respect than he had been accorded for hundreds of years. ‘Honor the emperor’ (or sonno) was a revolutionary idea in the late Edo period because it implied that attention, loyalty, and service were due to the emperor and, by extension, that loyalty to the shogun was contradictory to honoring the emperor.

This idea grew out of the School of National Learning which, stimulated by intellectual developments in China, emphasized the study of Japanese history. National Learning focused attention on earlier periods when the emperors actually ruled Japan. It was but a short step from historical studies to political statements which pointed to the modest situation of the emperor compared to the shogun. From this grew the idea that loyalty was due to the emperor. This was destructive to the decentralized feudal system which placed most power in the hands of the shogun as well as an important stimulus to the growth of a Japanese nationalism rather than a domainal nationalism. Loyalty to the emperor was a major force which unified opposition to the Tokugawa regime and led to the Meiji restoration.

Mention was made of the influence of the West on the end of the Edo period. This can be seen most clearly in the slogan ‘expel the barbarians’. ‘Expel the barbarians’ (or joi) was another of the major slogans which was employed in opposition to the Tokugawa shogunate in the last years of the period; it meant that the government should act to reject all new contact with Westerners, permitting only the centuries old trade with the Dutch at Nagasaki port.

As Western nations struggled to make contact with Japan in the first half of the 19th century, the Tokugawa government had to decide how to deal with the West since control of foreign affairs was a Tokugawa monopoly. The overwhelming strength of the West was well recognized and indeed underlined in the 1830s when the British defeated the Chinese empire. However, ideologically, the problem was made complex when Japanese foreign policy was simplistically defined as sakoku or ‘a policy of national seclusion’ (also called the ‘closed nation’ policy). Ironically, the term was one coined around 1810 to translate a European work on Japan which described the country as ‘closed’ to the outside, meaning closed to the West (the book ignored contact with the Dutch and with the rest of East Asia). The Tokugawa had maintained contact with nearby Asian nations and had not thought of its policy in these terms, but the word, once it was invented for the purposes of translating the European book, became a conservative rejection of change in Japan’s relations with the West.

Politically, the problem was also complicated by the Tokugawa government which felt it necessary to gain a consensus throughout Japan on how to deal with the West: this was a reflection of the uncertainty and weakness within the Tokugawa shogunate. Thus, following the 1853 visit of Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the US navy, the shogunate asked all the daimyo for their opinion on the matter, hoping to be empowered to pursue a new foreign policy toward the West. Unfortunately for the shogunate, the verdict was ambiguous and it had to act without clear support. This exposed the shogunate to a barrage of criticism; the opinion of the political public had been sought and, by implication, invited to be politically active at the national level for the first time since the beginning of the shogunate. The invitation, having been issued, could not easily be withdrawn. Critics of the government seized on the ideal of expelling the barbarians as what the Tokugawa should do, but was not doing after 1853.

As relations with the West expanded, the Tokugawa attempted to gain wider acceptance for its foreign policy by seeking approval from the imperial court. This attempt failed when critics manipulated the court to issue an order to the shogunate to expel the barbarians. When the shogunate failed to comply with the order, critics combined the idea of ‘expelling the barbarians’ with ‘honoring the emperor’ and argued that the shogun was disloyal to the emperor for failing to expel the barbarians. Accordingly, their policy turned toward the slogan ‘overthrow the shogunate’. This became a popular slogan under which the opponents of the Tokugawa government were able to unite. Unity had been extremely difficult to achieve. Institutional arrangements set individual feudal domains against each other and local loyalties deeply divided the Japanese. Ideas like ‘honor the emperor’ and ‘expel the barbarians’ were effective in uniting some disparate elements, but the idea of overthrowing the shogunate committed critics to rebellion.

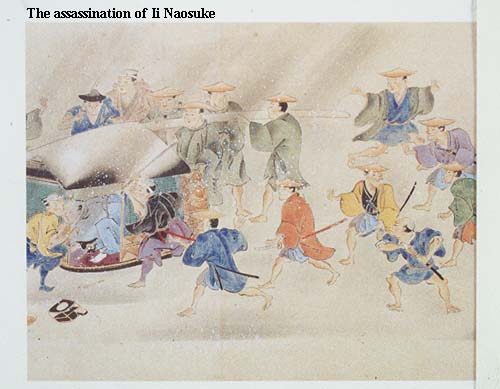

While these ideas made increasing numbers of samurai and some commoners opposed to the Tokugawa shogunate, many other factors also contributed to the end of that government. The structure of the Tokugawa system itself was one. The identification of some domains as tozama domains (‘outside’ or enemy domains) preserved for 250 years within the political body a level of antagonism which begged for release through rebellion. The historical viewpoint of the School of National Learning emphasized the military nature of the samurai class and encouraged many radicals to turn to their swords as expressions of their role in society: assassinations and attacks resulted on Japanese and foreigners leading to instability and uncertain leadership. It is possible to argue that the last visionary leader of the Tokugawa shogunate, Ii Naosuke, was killed by these radical swordsmen in 1860.

Overthrowing the shogunate was by no means simple. Each domain which rose up against the Tokugawa had to individually go through a process of struggle between conservatives and radicals. The conservatives argued that failure to overthrow the government would result in severe penalties, even the destruction of the domain. Once the radicals won, they were isolated until they could develop alliances with other like-minded domains. This was difficult in turn since the Tokugawa political system was based on limiting any contact between domains specifically because it might lead toward sedition. In the actual event, the major domains which overthrew the Tokugawa, Satsuma and Choshu, competed with each other throughout the early 1860s until finally in March 1866 (less than two years before the final battles) they negotiated a secret alliance against the Tokugawa.

The radicals, who were called ‘loyalists’ (or shishi) because they were loyal to the emperor, should not be assumed to be merely a negative influence on politics. They also served at least two crucial functions: they spread ideas which challenged orthodox ideology and they formed the conduits of contact and negotiation between domains which were necessary to bring together an anti-Tokugawa alliance. One of the contradictions of the Tokugawa political system was that it made every effort to keep the different domains and their retainers separate, but it also brought them together in Edo on alternate residence duty (sankin-kotai) and on the highways going to and from Edo and in Osaka carrying out the official commercial necessities of their domain. At the end of the Edo period, the loyalists also gathered in Kyoto, drawn by the magnet of the emperor, where they met and plotted assassinations but also dreamed and talked of alliances between their domains.