Properly speaking, there have been no dynastic struggles in Japan; only one dynasty has ruled Japan and it continues. That simplistic statement, however, covers up a lot of exceptions to the rule.

To begin with, Japanese emperors and empresses (there have been ten empresses with the last reigning from 1762-1771) have seldom exercised much power. The earlier ones were able to manipulate supporters on their behalf and occasionally more recent ones have too, but generally speaking, they reigned rather than ruled: other, more powerful men (like the Tokugawa shoguns) often exercised power on their behalf. Sometimes, however, struggles over the throne broke out. An example was the Jinshin Rebellion of 672 which saw a battle at Seta Bridge on the Nakasendo. The Rebellion was led by the brother of the former emperor who rallied enough military support to beat his brother’s son and designated heir. The brother installed himself on the throne in place of his nephew. This kind of power struggle certainly meant that the Japanese imperial line did not always flow directly from parent to child.

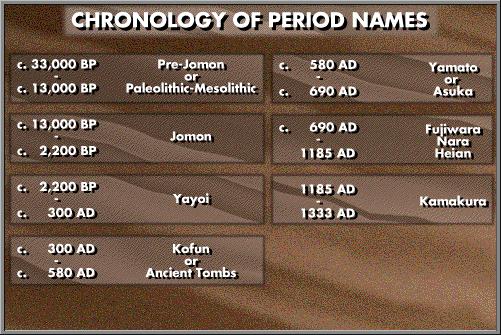

Manipulation of the emperor was common from very early on in Japanese history. For nearly three centuries from the middle of the 9th century, the emperors were heavily controlled by the Fujiwara family, a family with good pedigree in the imperial court. The Fujiwara were not only clever politicians, but they took advantage of the matriarchal nature of the imperial court to control the emperors. Marriage patterns at the time dictated that the wife stay in her own home and the husband visited. Children were brought up, then, in the home of their maternal grandfather. The Fujiwara were careful to marry daughters to the emperors, thereby ensuring that the heir would be subject to the influence and control of the Fujiwara family. The device worked so well and for so long that the period is often called the Fujiwara period.

A major break in the imperial line occurred in the 1330s. The Emperor Go-Daigo (reigned 1318-1339) sought to restore himself to power by authorizing Ashikaga Takauji to overthrow the last of the Kamakura (Minamoto) shoguns. Takauji did, but then turned against the emperor, cast him out of Kyoto, and established as emperor a man from a rival branch of the imperial family. Go-Daigo established a competing court until 1392 when it was agreed to alternate the imperial office between the two rival families. For the moment, it remained with the family which Takauji originally put on the throne. Takauji’s successors never fulfilled the terms of the agreement and the throne remained out of the hands of Go-Daigo’s descendants (the line only died out in the past twenty years and the last descendent was, arguably, the legitimate pretender to the throne).

If the Japanese case is different from other civilizations where imperial dynasties rose and fell amidst great turmoil, perhaps there is a degree of similarity outside the imperial family, particularly in the samurai families who actually held real power for most of the last thousand years. Here we do see real struggles for real power with numerous changes over time. Three different families (the Minamoto, Ashikaga and Tokugawa) fought for and controlled the pre-eminent office, the shogun, for long periods of time. Many other families rose by the sword to local fame and fortune for varying periods of time in these ten centuries; the Warring States period by its very name gives an idea of the extent and viciousness of struggle. Theoretically, the samurai class based its succession on the principal of inheritance by the eldest son, but often an ambitious younger son plotted an uprising or the eldest son was passed over in favor of a more able younger one.