The concept that the emperors and empresses of Japan are descended from gods was enshrined in the Shinto religion, in Japan’s earliest histories, and in the 1889 Meiji Constitution. Article 3 of this constitution stated in its entirety ‘The Emperor is sacred and inviolable’. In Japan’s earliest histories, however, the story is told at greater length. A pantheon of gods was described in the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki, beginning with Izanami and Izanagi, who created the world, and other gods. One of the main gods was Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess, from whom the imperial family descended. The myths form the earliest recordings of the Shinto religion which is native to Japan.

The early Japanese saw religion and politics as much the same thing. Hence, the events described in these histories saw the use of religion to support political arrangements. The myths and beliefs outlined were designed to strengthen a political system which put the imperial family and its allied clans at the top; thus, the histories describe a hierarchy which put the gods of the imperial family at the top of the heavenly hierarchy. The histories’ description of affairs prior to the middle of the 5th century is, of course, the stuff of fiction and mythology, yet they were the intellectual basis for the early Japanese state.

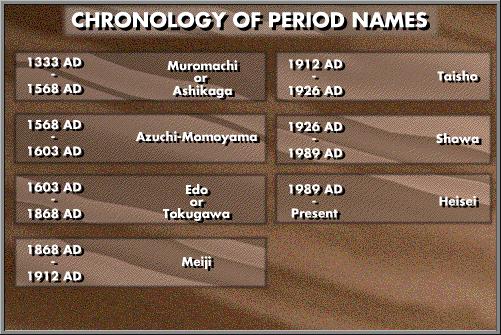

In the late Edo period, historians were influenced by developments in Confucianism to study ancient history and literature. Some of them turned to the Kojiki and other old histories as sources. Doing so contributed to a revival of attention and concern for the imperial family, particularly in the form of the School of National Learning. The nationalism which emerged took the emperor and his ancient divinity to heart and formed a crucial basis for the Meiji state, including its Constitution of 1889.

It is useful to bear in mind that the Japanese word for god, kami, is used in a very broad sense as well as in the sense of god as in the Christian, Jewish and Muslim religions. Kami is often used to indicate that there is an august presence or godliness surrounding a thing. The thing may be a particular place, a tree, or a rock, but the term can also be applied to an exceptional person either because the person is strong and charismatic or because the person is uniquely high born. This is a very diluted use of the concept of ‘god’.

straw ropes

After Japan lost World War II, the Showa Emperor made a public statement that he was not a god; he did not make clear whether he was using the word in the specific religious sense of the Europeans, or whether he meant the more elastic Japanese meaning. In either case, his statement did much to dispel the distance and majesty which had grown around the Japanese throne in the previous century. Thereafter, he made a point of appearing ordinary. He was a family man, frequently pictured with his wife and children, and he enjoyed research on marine biology, which resulted in many pictures of an informally clad man wading along the beaches and reefs near Tokyo. His son, the present Heisei Emperor continued the theme of being almost one of the people; he married a commoner, plays tennis whenever he can, and has allowed his eldest son and heir to find his own bride without forcing him to accept an arranged marriage.