Conditions which were extremely favorable to commerce began to appear, ironically, during the Warring States period. As sengoku daimyo unified and enlarged their domains, they found that although they perhaps wanted the independence which mercantilist policies promised, they could not remain aloof from a national economic system. In fact, many of the policies they pursued actually decreased their independence. Thus, each lord allowed into their domain goods from other domains which they could tax, but the cumulative effect was to increase commerce rather than restrict it severely. Similarly, every one wanted firearms, but only the lucky few could produce and export them; others had to sell and export local goods in order to purchase the expensive weapons.

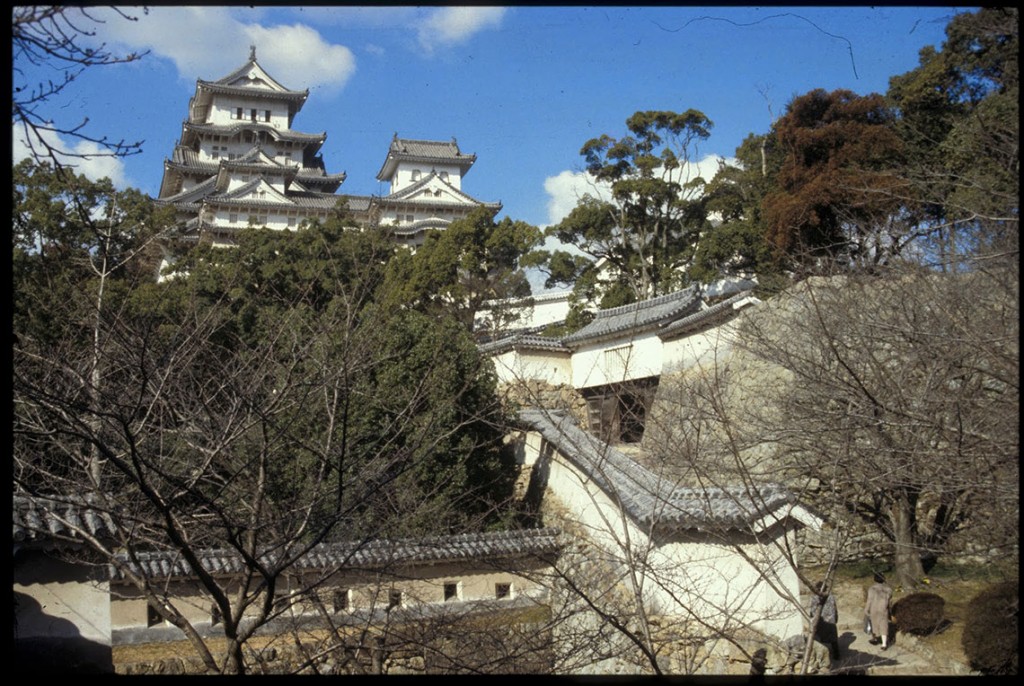

Daimyo, or feudal lords, also found it necessary to attract and maintain artisans who could produce the necessities of war and of luxurious living. Policies which attracted the free-spirited artisans included tax exemptions and grants of good land in the castle towns which were being established across the country. All of these policies contradicted the strict forms of Confucian social and economic systems which were favored as models by the samurai; these assumed an agricultural system in which commerce by merchants was given negative value.

Urbanization in the late Warring States and Edo periods also encouraged commerce. The social policies of the daimyo insisted that samurai reside in castle towns. Since the samurai did not produce manufactured items, artisans were required in the new cities. This class, in turn, required the exchange of money and goods to support their industrial efforts, so they relied on merchants who found many opportunities for commercial endeavor.

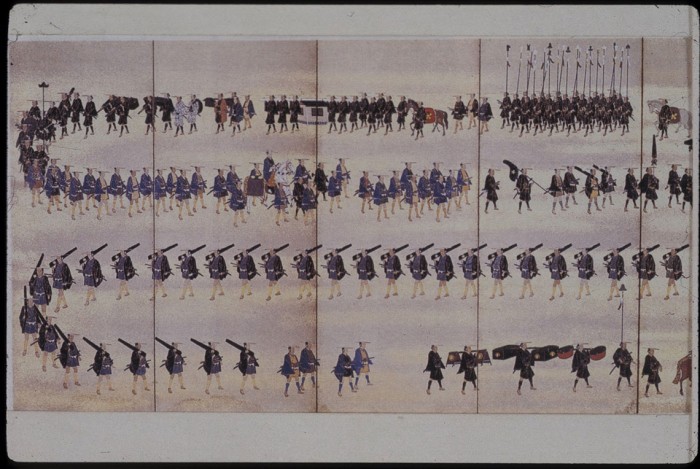

Urbanization was further encouraged by the system of alternate residence (sankin kotai) as hundreds and thousands of daimyo and samurai were required to reside for prolonged periods in Edo.

Urbanization contributed significantly to the rise of national commodity markets centered in Osaka. Complex shipping patterns brought rice and other commodities to Osaka by land and by sea. There they were exchanged; cash and credit were transferred widely within Japan and huge amounts of commodities were moved on to Kyoto and Edo. Great merchant families grew up. The most infamous family was the Yodoya family which prospered for two generations as a rice merchant. Perhaps because they were too successful and too materialist for the austere samurai rulers, the Yodoya suffered having their worldly goods confiscated in 1705, including 250 farms and fields, 3.5 million gold ryo (a unit of currency: the weight was 146,000 pounds), 14,000,000 silver ryo (583,000 pounds by weight), carpets, crystal, sliding doors, over 500 houses and warehouses and more (or so it is said, probably with exaggeration).

As with commercialization elsewhere, the Japanese during the Edo period saw considerable specialization of commerce. Particular areas were best suited for production of, for example, indigo for dying cotton; they became centers for industrial production of finished cotton goods. Urban demand for goods encouraged commercial specialization and the reliance on merchants to facilitate commercial exchange of goods and money. Some of the most successful commercial agents during the Edo period were those which were chosen for special privileges by the various governments of the day. Thus, in 1691 the Tokugawa shogunate chose as one of its official merchants (goyo shonin) the Mitsui family which had commercial operations in both Kyoto and Edo. The Mitsui operation was used to move cash receipts from Osaka to Edo, but gradually expanded well beyond banking transfers to all kinds of commerce. The Mitsui family formed the basis for the vastly important Mitsui companies which still play a major role in the Japanese, and global, economies.

Employees inside their place