Contact between Japan and China goes back to around 200AD, according to the Chinese histories, and the influence of China on Japan is as deep as it is long. Whether you look at language, culture, political institutions, or the Nakasendo itself, Chinese influence is readily apparent. At the same time, Japan has always remained different, forced by the fundamental differences between things Japanese and things Chinese to adapt rather than merely adopt Chinese influences.

Japan’s earliest literary and historical records reveal the appeal of Chinese civilization which was so far superior that there was an early tendency to take on Chinese models wholesale. Buddhism, Chinese language and literature, and the technology of government proved at a glance to be more powerful than their Japanese equivalents. Take language as an example; the Japanese had no written language, so Chinese soon proved essential in the process of political unification under the imperial house. The earliest historical records (the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki from the seventh century) were an attempt to weave together Japanese religious beliefs such that the goddess of the imperial family was at the top. This literary exercise was intended to underline the political supremacy of the family using the power of the written word plus religion. Modern readers may easily recognize inconsistencies in this semi-religious, semi-political structure, but undeniably, setting it down in the only writing system available, Chinese, was more effective than passing the message on by word of mouth.

The Buddhist religion came with the rest of early Chinese culture and made an impact. Buddhism was a coherent set of beliefs which forced the native traditions to define themselves as an alternative to the Chinese influence. At the same time, Confucian concepts of government and society also arrived in Japan. Soon, the imperial court was organized on Confucian principles with a bureaucracy which paralleled the Chinese model in title, rank and function. Chinese concepts of cities and agriculture were also brought in. The Japanese constructed a series of cities based on Chinese plans for capital cities. Nara and Kyoto still show the inspiration of this model. Chinese architecture, for example is much more ornate than traditional Japanese architecture. The difference can easily be seen in Buddhist temple (Chinese) and Shinto shrine (Japanese) architecture. A glance at an aerial photograph of the areas around these old capitals shows a system of fields and irrigation carefully divided into even rectangles on the old Chinese model.

Although China was taken as a model, it did not fit well. Kyoto might be based on the plans for northern Chinese capitals, but Japan was never able to fill out the city limits until this century. Gradually, Chinese characters came to be read sometimes with an approximate Chinese pronunciation and sometimes with a Japanese one: the character for ‘new’ can be read alternately as shin or atarashii. Institutions of government failed to cope with the rise of civil disorder and the samurai class which developed systems of rule that turned away from Chinese models. In all these cases and many more, Chinese influence is discernible, but centuries of experimentation to meet the strains of historical change brought forth a very different, Japanese system.

Chinese civilization flowed out of China and into Japan in several waves, depending on Chinese strength and Japanese receptivity. The late Warring States and Edo periods saw the most recent surge. Contacts with China were renewed, particularly in the decades surrounding 1600, and influence flooded in. Neo-Confucian values, learning and philosophy, and Zen Buddhism were major imports; use of a road system to speed communications and tighten control was revived. Differences between the two societies, however, remained pronounced and perhaps even became more so, for the Japanese now critically sought out influences which would strengthen them and paid little or no attention to the remainder.

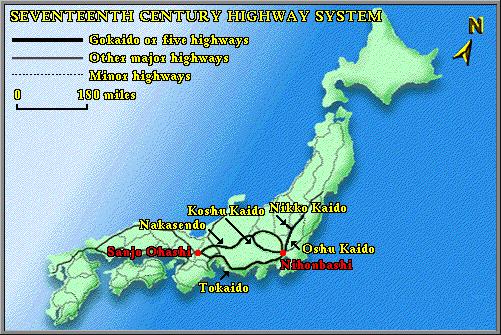

17th century Highway System