At the time of the Meiji Restoration, in 1868, some 250 castle towns (jokamachi) formed the core of a well developed urban network in Japan. Although constructed primarily as defended residences for provincial lords (daimyo) and their retainers, castle towns necessarily became local administrative headquarters through which political authority was channeled from the shogun’s citadel in Edo (now Tokyo) to all parts of the Japanese countryside.

The ‘sword hunt’ of 1588 had effectively disarmed the rural gentry and forced all professional soldiers to reside in ‘urban’ places. Moreover, an edict of 1615 had ordered the dismantling of all but one castle in each of the 250 or so provinces. Thus, castle towns became the focus of all military activity in Japan, and large garrisons of soldiers were housed in them. On average, about half of the population of each castle town comprised members of the military class (samurai).

In turn, the samurai were strongly dependent on artisans and merchants for the provision of military equipment and other necessities. As commerce developed in Japan, the castle towns became the economic as well as the political centers of each province, and the merchant classes were increasingly attracted to reside in them. In a society where the feudal hierarchy was rigidly upheld, a precise spatial arrangement of urban functions was required to separate the samurai from other townspeople (chonin). In this way the layout of castle towns reflected the structure of 17th century Japanese society.

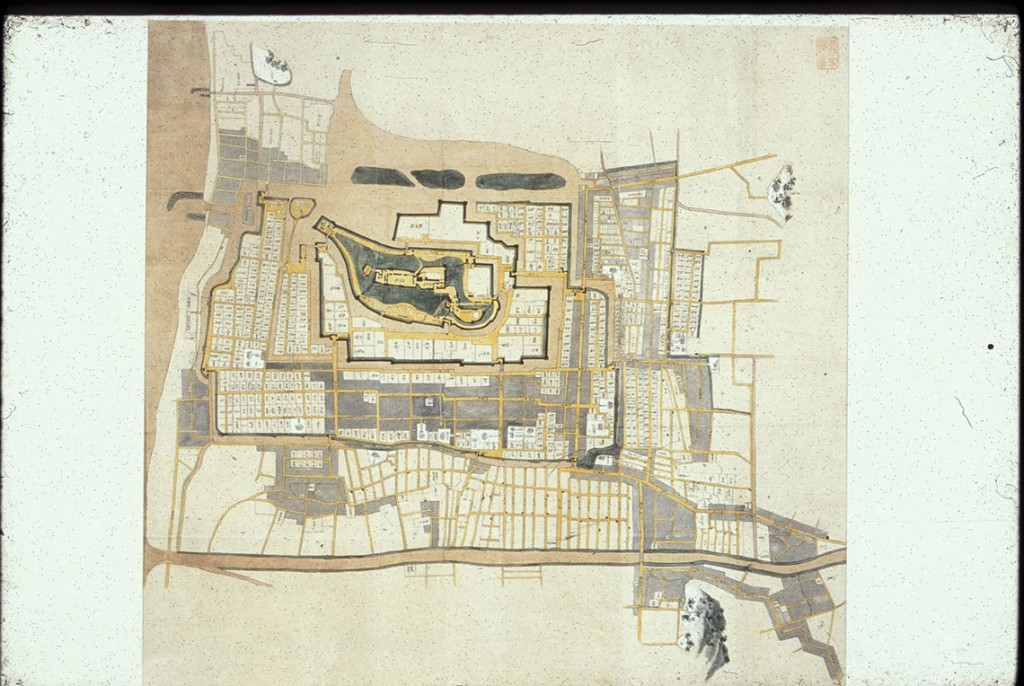

At the center of the castle town, often situated on a prominent mound or small hill, was the castle itself. This strongly fortified structure, invariably surrounded by a moat, incorporated the residence of the feudal lord, the daimyo.

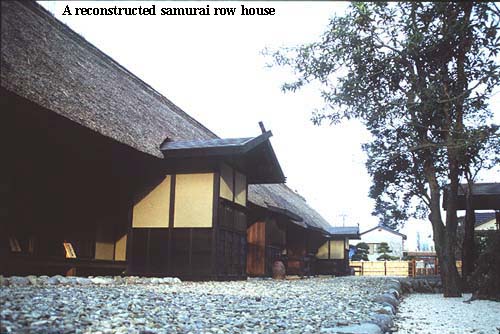

Immediately adjacent to the castle, usually in an area between the moat and a second, outer, moat, lived the highest ranking samurai. Since the distance of a samurai’s residence from the castle was considered to reflect his status in the social hierarchy, areas further away from the castle housed people of progressively lower rank. Although each samurai had his own group of retainers and foot soldiers, it was normal practice to house each status group within spatially discrete blocks of the town. By physically separating retainers from their samurai masters the daimyo was able to subject all solders to his direct rule, and thus maintain the peace.

The townspeople (chonin), comprising merchants, artisans, and laborers were also assigned discrete blocks or wards within the town. Although they held a lower social status than the samurai, the chonin did not necessarily live furthest away from the castle. Some privileged merchants and craftsmen, perhaps commissioned by the daimyo himself, were often allowed to reside in premises adjacent to the quarters of the highest ranking samurai. A typical pattern was for chonin to reside in wards forming narrow strips separating different groups of samurai. Usually such strips would be alongside the major thoroughfares, where access to the services they offered was most convenient for all people. In addition to these wards, other chonin occupied large, distinct, ‘commoner’ wards within the town. These, in turn, were often subdivided into different blocks — each representing a particular craft or trade. The residents of one block, for instance, might all be builders or carpenters, while those of another might be predominantly sake brewers.

The internal arrangement of castle towns was often broken by complex moat systems and, near the castle, by lines of fortifications. Only very rarely was the town itself surrounded by a moat or wall. (One notable exception is Kyoto, where a wall was constructed around the city by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the 16th century). Many residents on the edge of the town, therefore, had direct access to agricultural land, and could supplement their livings by farming. In order to prevent infiltration by hostile forces, however, strategic entrances to the castle towns were ‘guarded’ by trustworthy samurai, housed in large, easily defended residences. In the same way, temple complexes were usually located at the edge of the town, and arranged so that buildings and courtyards could be effectively defended in times of crisis or attack. Such defenses could probably offer no more than token resistance against a well organized attack, but an enemy advance towards the central citadel was likely to be further hampered by arranging the street pattern in a series of ‘dog-legs’ and cul-de-sacs. By such means it was hoped that enemy forces would become sufficiently confused, or even lost, to provide extra time for the main body of castle defenders to organize themselves efficiently.

The individual layout of each castle town was determined ultimately by the limitations of local topography and by the whim of the daimyo lord. The general characteristics, however, seem to be common to most castle towns in Japan, indicating that a nation-wide consensus on the basic principles of castle town layout existed. In part this reflects the powerful control which the Tokugawa shogun exercised over all Japan between 1600 and 1868, ensuring that the shoguns edicts concerning, for example, the differentiation of social class, were strictly enforced. It may also reflect the fact that most castle towns were established within a very short period, between 1580 and 1615, and that the same architects were sometimes employed to construct different castle schemes.

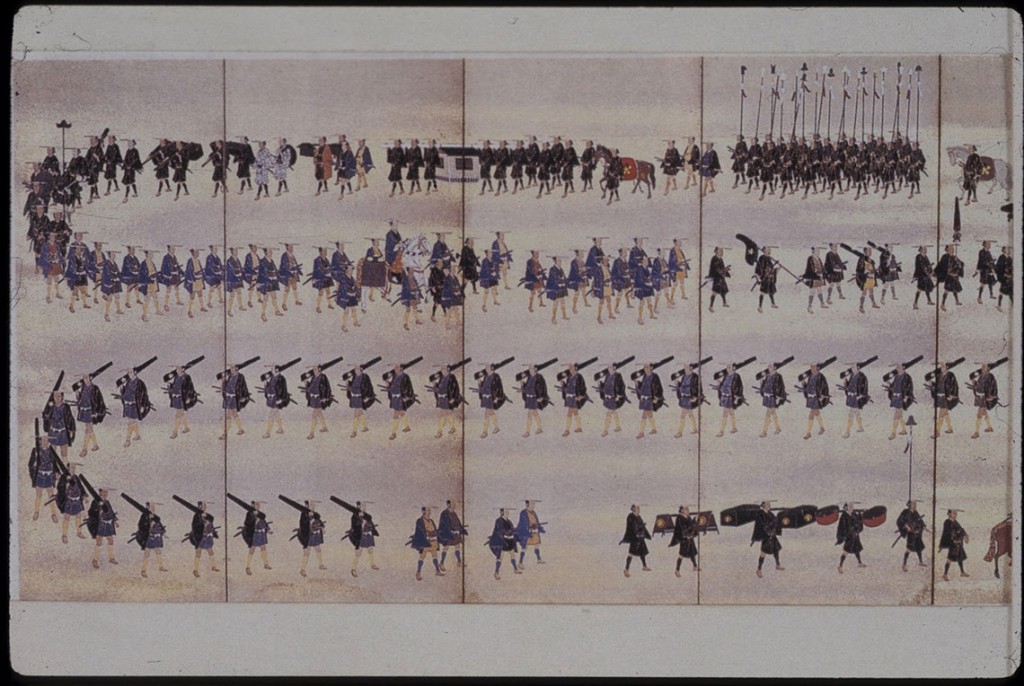

Perhaps the most crucial factor ensuring a strong degree of uniformity, however, was the institution known as sankin kotai, or alternate residence. This was established in the early years of Tokugawa rule as a means to control powerful daimyo scattered over all parts of Japan. The system required that the immediate family of each daimyo should live permanently in a residence within the environs of Edo, and that each daimyo should also spend at least half his time in attendance at the shogun’s court. Thus, on average, most daimyo spent one year at Edo, and the subsequent year in their own province, and so on. continual movement of daimyos and their retainers, often numbering many hundreds of people, to and from Edo acted as a great stimulus to trade, commerce, and communications generally. Regional specialization of manufacturing activity, and of processing agricultural items were also enhanced. It also meant that ideas and innovations formulated in one part of Japan were rapidly circulated, via the shogun’s court, to all other parts of Japan. Castle towns tended to assume a remarkably uniform character, following the lead of the largest and grandest castle town of all — Edo.