Bathing seldom appears as a major topic in books about Japan of a ‘serious’ nature. Historians and geographers alike usually look at more ‘significant’ topics although they will gladly extol the pleasures of a hot bath if you ask them face to face. The bath, or ofuro, however, is hardly insignificant. Not only does it end the day for nearly the entire population, but in the form of urban public baths or rural spas with supposed medicinal effect, it is a large-scale business.

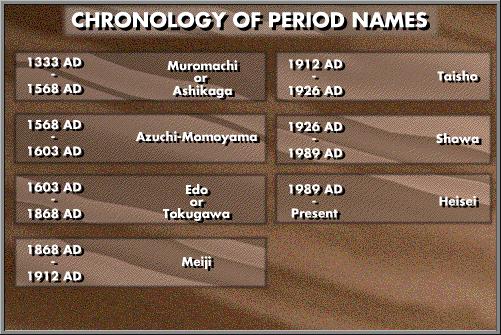

Bathing became widely popular during the Edo period as a communal activity which was healthy, social, and relaxing. Indeed, as the world has discovered, the Japanese way of bathing is an experience that everyone can appreciate.

Bathing is straight forward. The bather enters the bathing room, pours water over the body, washes with soap, rinses with more water and finally climbs into the bath tub. The bath can be extended by climbing out again and repeating the process or by climbing out to take a cold rinse before going back into the hot water. Bathers who are not used to very hot water must either expel themselves from the water quickly or stay very still; the body cools the water in the immediate vicinity, but movement brings it into contact with hot water again.

The bath must be approached with some caution. Young children, the elderly, and people with weak hearts or a history of strokes must take care not to enter water that is too hot.

Water for a bath is normally heated by drawing it out of the tub, through a heater, and then back into the tub again. The preferred type of bath, however, is a bath fed by a hot spring. Hot spring water contains a variety of natural components (often sulfur) which are said to be soothing to the skin and muscles as well as some internal organs. Particular hot springs are famous for curing different ailments and are much preferred.

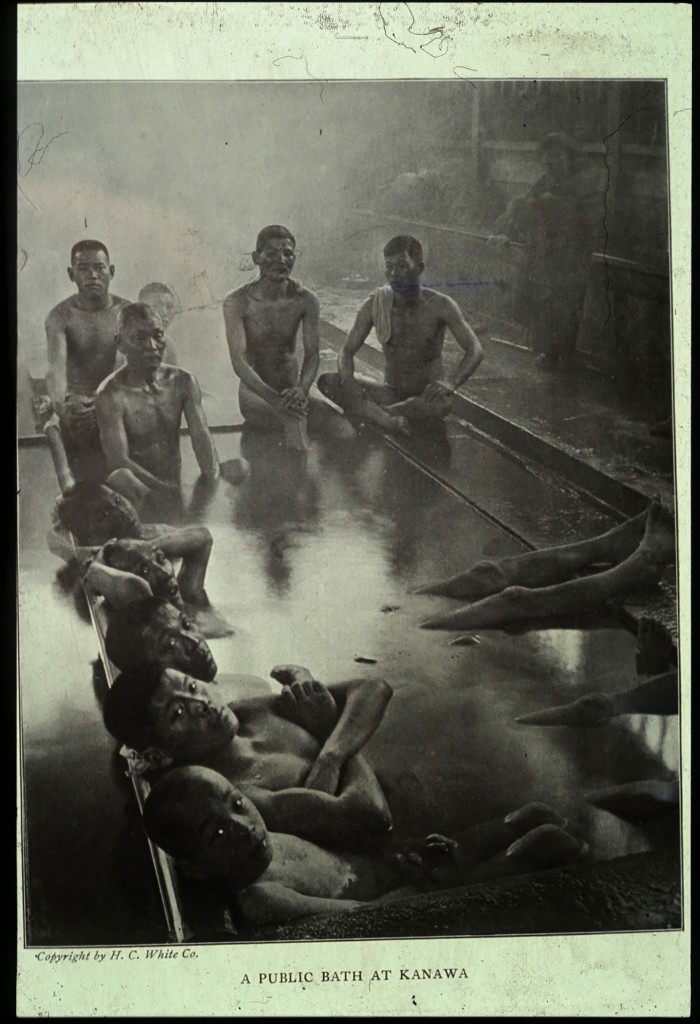

Until the mid-nineteenth century and contact with Western culture and morals, a Japanese bath was usually communal: men, women and children together. The first commercial bath was opened in Edo in 1591 and quickly became popular. Few people had a bath in their home, so most bathing was at the local public bath or sento as it is called now. This made the bath a place to meet at the end of the day. While washing and soaking, people would talk over the problems of the day. Complaints and tensions between people could be soaked out together with aches and pains. Gossip and political chatter were common currencies while children could plot tomorrow’s action. The bath was a true center for the community. While the body was cleansed, the social fabric was scrubbed and restored to an equal level of perfection. In addition, bathing was taken into the entertainment districts where bathers could be cleansed and massaged at the tub-side before deciding to retire upstairs for additional pleasures.

Communal bathing became frowned upon after the Meiji restoration. First in the main cities of Tokyo and Osaka around 1870 and then slowly throughout the rest of Japan, mixed bathing met with official disfavor. New ideas of ‘civilization’ which frowned on such mixing of the sexes were brought in from the West. Mixed bathing carried on for many years, however, and could still be found in the 1960s, but is virtually extinct now. Large baths, on the other hand, still abound. At popular spas, large, single-sex baths are the rule and the sento in big cities also have baths capable of fitting in twenty or thirty people at a time. Public sento are having trouble staying alive, however. So many homes now have their own baths that fewer and fewer people are going to the public baths. When fuel costs rise sharply, as they did in the 1970s, the sento had severe problems. Some put in automatic washing machines and hairdryers to strengthen their appeal, but the number of sento is steadily decreasing.

Along the Nakasendo, most of the traditional inns have small baths. As is common now, there is a room for women and another one for men, but in both cases, the tub usually fits only two people. Some of the tubs are made of plastic and fiber glass such as you would find in most private homes, but most inns still have wooden tubs which give off a pleasing scent when new.

Bathing is also put to ritual use. In the spring, iris stalks are put in the bath in conjunction with the former holiday, Boys’ Day. The characters used to write ‘iris’, ‘victory’, and ‘honoring the martial arts’ are all read shobu. Iris, then, were put in the bath to bring to boys victory and skill in the martial arts. In the early winter, citron are floated in the hot water. The fruit is thought to protect people against winter’s cold. The bathing room takes on a heady bouquet of citrus orange.

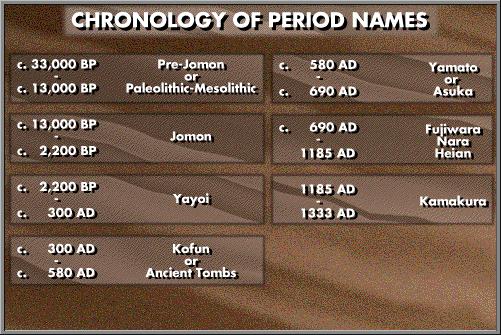

The origins of bathing go back to the earliest times and the most fundamental beliefs of Shinto. Mention of bathing appears in the first histories while Shinto myths of creation and the activities of gods frequently involve concepts of pollution which is best removed with water. What some cultures call sin, Shinto called pollution. It was often equated with physical dirtiness. A bath could wash away the pollution, leaving the worshipper clean, whole, and human once again. The concept of bathing, to be a bit philosophical, has profound implications regarding the impermanence of dirt relative to the permanence of sin. Thus, bathing is not only relaxing and physically cleansing, but it combines an everyday event with the foundations of the native faith.

Let there be no mistake, however; bathing as an everyday event is recent. In the Heian period, bathing was seldom performed more than twice a year and was viewed as a potentially life-threatening activity. Later, monks regularly purified themselves by bathing, but they probably regarded a hot bath as a luxury unless it was a holy spa or a hot spa regarded as a medicinal restorative. Commoners took regular plunges in the ocean or in rivers, especially in summer.

Modern baths seem to stretch the concept of the ofuro to the extreme. A bath in a gondola suspended beneath a ropeway over a scenic place is far removed from a public bath of the period with young and old, male and female gathered for a cleaning as well as a good soak and a bit of relaxed conversation. So too, the social lubricant of the communal bath is abandoned now that most families have baths in their own homes. In fact, most families have a strict rotation through the bath so that everyone gets a separate turn. Changes in fashion have put people in Western-style clothes 99% of the time, but the bath remains firmly entrenched in Japanese society even though it has lost its function as a place for social intercourse.