Compared to other developed nations Japan has a relatively small amount of land available for agriculture. In fact, only 16 percent of the land surface is suitable for cultivation, yet a comparatively high proportion of the workforce is engaged in farming. As a result, Japan has one of the highest densities of farmers per acre of agricultural land anywhere.

Since the introduction of rice cultivation in the Yayoi period (300 B.C. – 300 A.D.) rice has remained the dominant crop in Japanese agriculture. The significant feature of rice cultivation is not only that rice is highly nutritious and easily stored, but that cultivation requires well organized, collective labor and close cooperation between different groups of farmers. In other words, the introduction of rice not only changed the physical appearance of the landscape, it also demanded profound changes in social structure and organization. Of particular importance are the need for large amounts of co-operative labor during the busy summer transplanting and autumn harvesting seasons, and the need for close inter-community co-operation for the storage and channeling of water. When rice cultivation had spread to most parts of Japan, about two thousand years ago, farmers were forced to organize themselves in settlements of up to 30 to 40 households. This remained the essential pattern until recent years, when rural depopulation in remote areas brought about a decline in the number of farm households in many villages and suburbanization brought about an increase in the size of villages on the outskirts of big cities.

Agriculture has long been important to the economy of Japan. In the Edo period the wealth of a daimyo was measured in terms of how much rice his land produced. There was constant desire, therefore, to increase the amount of land under cultivation by reclamation of upland forests and low lying marshlands. In the Meiji period it was the farmers who, to a large degree, funded the initial wave of modern industrial expansion by the payment of a burdensome land tax. Unfortunately the financial strain on many of the smaller scale farmers was so great they were obliged to sell their land and pay rent in order to continue farming it. This change to a system of tenant cultivation rather than owner-operation led to a gradual decline in productivity. This was viewed seriously by the Americans who, in the Allied Occupation of Japan after World War II, realized the urgent need to restore food supplies to a defeated and starving nation. A program of land reform was devised to restore ownership of farmland to the people who worked it. While successful in this objective, and in restoring agricultural self-sufficiency to Japan, the reform together with the postwar depression also brought about an increase in the number of farm households, to reach more than six million by 1950. This in turn meant that the problem of small scale farming persisted, with most farmers having just enough land to tie them to it, but not enough to provide a decent living from full-time agriculture.

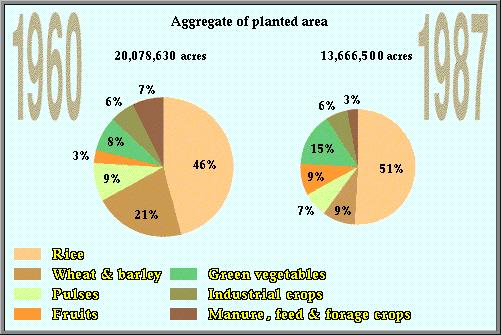

Further major legislation was carried out in 1960 by the Japanese government with the enactment of the Agricultural Basic Law. The government wished to promote agriculture so that valuable export earnings from manufacturing industry would not have to be spent on the purchase of imported foodstuffs. Such funds would have to be reserved for the import of other vital raw materials if the economy was to grow. The problem was that, given the small scale of most farms, many farmers earned much less income than workers in manufacturing industry. Already it was becoming clear that young people preferred now to leave the rural sector to take advantage of better paid work in urban areas. The specific aim of the Basic Law, therefore, was to improve agricultural productivity (and thus income), by encouraging the introduction of new technology and greater crop diversification.

The promotion of technological developments in agriculture met with spectacular success. New machines were developed in the 1960s and 1970s which not only overcame difficulties of usage in minuscule fields, but also led to a reduction in the number of labor hours to only one-quarter of previous requirement. In other words, the work previously carried out by four people could, by the mid 1980s, be undertaken by just one. Equally important, the development of mechanical harvesters and the rice transplanter meant large amounts of labor were no longer required at the busy transplanting and harvesting seasons. The rural exodus continued, therefore, but without immediate detriment to agricultural production. In fact, with the increased use of pesticides and chemical fertilizer, in addition to field consolidation programs and improvements in irrigation, rice yields have virtually doubled in the last 40 years.

Rice transplanter

The saving of agricultural labor through the introduction of modern technology and farm management techniques has had another major impact. That is, the people who have decided to continue farming their small plots of land are able to do so by working weekends only, although they may be helped out during other times by aging parents who have no other work to do. This frees farmers to find other, non-agricultural work during weekdays, especially if there are plenty of job opportunities within easy commuting distance. As a result, the proportion of farmers engaged full-time in agriculture has declined dramatically from 50% of the population in 1950 to less than 15% in 1990. In effect this means that most farm households receive two incomes and that, on average, average farm household income now tends to be higher than average non-farm household income.

The future may seem bright, therefore, but the reality is very different. One problem is that since the war the government has purchased the rice produced by farmers on a price support basis. Before the 1970s this system seemed to work, for it enabled full-time farmers to maintain at least a reasonable standard of living. The difficulty was that farmers had no incentive to grow anything but rice, and too much was being produced. To complicate matters the price support made Japanese rice the most expensive to produce anywhere, and consumers became attracted to alternative food products, often imported from abroad. With a huge rice surplus building up, government was forced to cut its agricultural subsidies and agricultural incomes began to fall after the mid1970s. Farmers were also encouraged to cut back on rice production, but relatively few in this aging workforce had the desire to switch to other crops. Only in the farm areas on the suburban fringe, where market garden crops could be grown profitably, was any major change seen in the agricultural landscape.

Today, one-third of all farmers are aged over sixty and the agricultural population continues to age rapidly. The hard physical work involved, in a situation of falling agricultural profits, means that relatively few of the young people who left during the rural exodus are likely to be persuaded back to the farm. Even if they can be, many will have virtually no knowledge of agricultural operations. Aside from profitable farming areas on the urban fringe, or in a few areas of specialist production, the future for most rural areas looks bleak. Only the possibility of further expansion of part-time farming holds any real hope for the future survival of most agricultural settlements as they exist today.